Akram Hamid scrubs the grease off his hands after a day of labor in Abu Kamal, a small Syrian town not far from the Iraqi border. Twenty minutes later, the mechanic rides his motorcycle past the autumn-dry rushes along the west bank of the placid Euphrates River, to al-Sukariya, happy to start fishing. It is dusk on a Sunday in October and the turned earth of the fields is pungent. Scattered farmers amble slowly home. A few late-season frogs pulse beneath the birds, chattering and thrashing in the rushes, as Hamid gets off his bike and scoots down the bank to drop his line.

He feels the rhythmic thwup-thwup in his stomach before he sees the helicopters. He stops to watch. He has seen helicopters, but not like these, and never four so close together. They display no markings of the Syrian Air Force, and they are the wrong color, painted black. He sees a B and a four. And they are flying low. When the door-gunners open fire, Hamid throws himself against the angled bank of the river. The men are shooting everywhere, firing from the air, spraying the ground.

He feels the rhythmic thwup-thwup in his stomach before he sees the helicopters. He stops to watch. He has seen helicopters, but not like these, and never four so close together. They display no markings of the Syrian Air Force, and they are the wrong color, painted black. He sees a B and a four. And they are flying low. When the door-gunners open fire, Hamid throws himself against the angled bank of the river. The men are shooting everywhere, firing from the air, spraying the ground.Suddenly, the formation splits apart. Two helicopters hover just above the cinder-block walls that enclose a small farm, 300 feet away. One disappears inside the farm, and the last one lands about halfway between him and the wall. Eight men in uniform leap out and run quickly, crouching low, carrying weapons. They are not Syrians. They take cover farther up along the same bank, several hundred yards away.

Shells from the air are tearing out chunks of concrete, punching holes through the cinder blocks as if it were paper. The noise of the guns and motors is deafening. Hamid pulls himself along the rutted ground, peers fearfully over the edge of the bank, and slithers away, taking advantage of a lone tree for cover. He does not understand what is happening.

Some of the eight soldiers on the ground move forward and take up positions outside the high walls, but they don?t seem to notice him. The hovering helicopters continue firing, tearing up the ground between him and the farm. “I thought it was safe because they didn’t shoot at me,” Hamid says later. After watching for about 15 minutes, he jumps on his bike to escape but, he says, “that’s when they shot me.” A bullet rips through his right arm, breaking it, mangling the muscles and nerves badly, and knocking him to the ground. Struggling to his feet, he sees the soldiers watching him as they climb into the helicopters and leave. “I was the last one they shot,” he recalls. “No one was shooting at the soldiers,” Hamid continues with certainty. “No one was shooting back.”

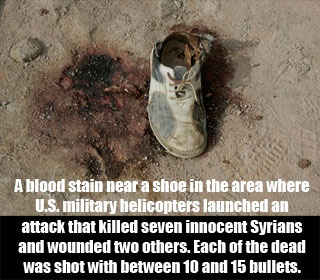

Despite his serious wound, Hamid was lucky. U.S. troops—possibly special operations, according to some sources—killed seven people inside the walled farm that day: a father, his four sons, including a teenage boy, the father’s visiting friend, and the night watchman. They also severely wounded the night watchman’s wife. She and her six-year-old son, along with Hamid, would be the only survivors.

On that day, one year ago, four American helicopter gunships crossed the border from Iraq, flying about five miles into Syrian territory. Anonymous Pentagon sources said at the time that “a senior al-Qaeda terrorist,” nicknamed Abu Ghadiya, had been killed in the raid. Ghadiya allegedly played a key role in smuggling men and arms across the Iraqi-Syrian border to attack American troops. According to George W. Bush’s doctrines of pre-emptive war, the United States reserved the right to cross borders if the leaders of other countries failed to combat those it had designated as terrorists.

Larry Johnson, a former C.I.A. analyst and now a consultant to army special operations, who has spoken to people with knowledge of the raid, says the U.S. was sending a message to the Syrians: “We’ve told you in the past to stop it. Now we’re serious.” He calls the raid “a Jim Croce incident,” referring to the 1970s singer known for the lyrics “You don’t tug on Superman’s cape / You don’t spit into the wind / You don’t pull the mask off the old Lone Ranger / And you don’t mess around with Jim.”

But Superman’s cape looks decidedly different from Syria and the rest of the Middle East. What was a small blip in the American news cycle became front-page headlines across the Arab world. The raid was seen as an act of war.

Serious questions about the raid remain to this day. It appeared curious to some—including former C.I.A. field official Bob Baer—that the United States military would have successfully brought down a major terrorist without issuing a photograph or displaying other proof. The U.S. government made no official announcement about the raid. Certain government officials we spoke to regret that the attack was nothing more than another unsuccessful example of the Bush administration’s cowboy tactics.

Serious questions about the raid remain to this day. It appeared curious to some—including former C.I.A. field official Bob Baer—that the United States military would have successfully brought down a major terrorist without issuing a photograph or displaying other proof. The U.S. government made no official announcement about the raid. Certain government officials we spoke to regret that the attack was nothing more than another unsuccessful example of the Bush administration’s cowboy tactics.

The Syrian government’s reaction was surprisingly mild. Although demonstrations occurred in a town near al-Sukariya, Syria merely filed a complaint with the United Nations Security Council and ordered the closing of a cultural center and a school run by Americans. Did the low-key response reflect a tacit admission by Syria that the U.S. was correct?

The deaths at al-Sukariya never surfaced in the U.S. as a 2008 campaign issue, and the raid—likely because the human toll has been obscured by America’s longitudinal two-front war—has been virtually forgotten in this country. However, solving the mystery of what actually happened one year ago, on October 26, 2008, is critical to understanding the reach, repercussions, and possible limits of U.S. military power. It may also provide valuable lessons for the Obama administration.

Was the incident a necessary blow against a shadowy terrorist enemy? Or was it an ill-conceived military adventure that risked alienating a potential ally and enraging the public? As we now see with the United States? cross-border drone attacks in Pakistan, threading that needle may prove to be one of the most vexing problems facing the Obama administration. And the thread begins for us in Syria.

On the Road to Damascus

Boarding the plane for Damascus, we make an unlikely reporting duo. Journalist and book author Reese Erlich, an American Jew, so resembles a Middle Easterner that native Syrians instinctively address him in Arabic. He has filed scores of stories from the region since 1986. Peter Coyote, an actor, book author, and former official in California’s state government, is making his first trip to the region. Tall and blue-eyed, Pete, who is also Jewish, stands out in the Middle East as obviously of European descent. Furthermore, due to a long career in film, he is impossible to disguise. Even people who don’t know precisely who he is know they?ve seen him somewhere before.

His introduction is intense. Our trip would take us from Damascus, through the warp and weft of Syrian officialdom, Iraqi resistance groups, Middle Eastern pundits, and finally to al-Sukariya.

Before all that, however, we have to get from the Damascus airport to the hotel—no easy task. The first cab driver wants the equivalent of $50 for the trip. The second and third offer their services, extoll their excellence, and bargain with hand gestures and body language. The deal is closed at $15.

A half-hour later, we arrive in downtown Damascus at the Cham Palace, a once majestic hotel now humbled by the arrival of a Four Seasons and a Sheraton. The reception area is an overwrought confection of white marble and dark wood that is intricately inlaid with mother-of-pearl. Several men wear checked headscarves called keffiyahs and robes, smoking idly and staring into space. Most others dress in Western-style suits. All clutch cell phones.

In many ways the hotel resembles Syria itself, with one foot in the Arab world and the other extending toward the West. President Bashar al-Assad is closely allied with Iran and takes a hard line against Israel. But he is also on friendly terms with France and a vocal critic of al-Qaeda and the Taliban.

Politics in the Middle East is nothing if not complex. Syria allied itself with the U.S. during the first Gulf War against a common enemy, Saddam Hussein. President al-Assad also provided the U.S. with valuable intelligence on jihadist groups in the years following the attacks on the U.S. on September 11, 2001. In 2003, however, U.S. policy shifted. The Bush administration began emphasizing Syria’s close ties with Iran, its meddling in Lebanon, and its alleged support for terrorists infiltrating Iraq through Syrian territory. (Syria has also been on the U.S. government?s list of state sponsors of terrorism since 1979.)

A Syrian man looks at the al-Sukariya farm the day after the U.S. military helicopter attack last year. By Hussein Malla/A.P. Images.

Syria, under “emergency rule” since 1963, is controlled by a secular authoritarian government that tolerates little dissent. On Reese’s previous trips, he was free to travel around the country without close scrutiny from the government. But al-Sukariya is a special case. American reporters can’t simply drive out to al-Sukariya and expect to conduct interviews. Authorities must be notified of travel plans and permissions granted. That’s how “Nana,” a local journalist and fixer, joined our modest caravan. (Because she was moonlighting, she asks that her real name not be used.)

Nana smokes furiously while texting on her cell phone, her brow furrowed in concentration. She’s trying to arrange an appointment with the minister of information, who can authorize our al-Sukariya visit. She appears continually distressed and vexed by this task and frustration clings to her like a haze of perfume.

Politics here, we discover, is like politics everywhere: you work your way up the chain, forging relationships and connections in the hope of eventually reaching someone with the authority to say “yes.” Pete observes that this process mimics the selling of a script in Hollywood. Usually only one person per organization has the power to green-light a project. Until you reach that person, all strategies are directed toward seducing underlings to forestall the dreaded “no,” which would maroon a project altogether.

Nana’s fervent supplications to her cell-phone gods produce an unlikely catalyst who later creates an unexpected fission. Prince Hashel Bin Zayed al-Mobarak arrives at our hotel with a flourish, introducing himself as a member of Bahrain’s royal family and announcing that he will accompany us to a meeting with the minister. Impeccably dressed, with military posture, the Prince radiates charm and appears unflappably at ease. His mustache and goatee are beautifully trimmed. His skin and movements appear well oiled.

The Prince describes several of his construction projects, which, if true, would put him on par with Bechtel and Halliburton. But he has none of the bodyguards or minders that normally surround such men. He drives himself around in a used Peugeot sedan, noting that “one of his wives” is driving the Mercedes.

Then Prince Hashel summarily announces, “I own Chinatown.” Pete laughs aloud and quips, “Funny, you don’t look Chinese.” The Prince explains amiably that he has had 17 wives and currently has 46 children by 10 of them. “One of the wives is Chinese,” he offers, as if that explains everything. We are definitely not in Kansas anymore.

Later, we contact the Bahraini Embassy in Washington for background information. The press officer says Prince Hashel is not a member of the royal family and pointedly notes that he doesn’t even share its last name. (Prince Hashel did not respond to our follow-up request for clarification.)

For all his self-aggrandizement, however, Prince Hashel—or whoever he is—does win us an audience with Syria’s minister of information, Dr. Mohsen Bilal, an elegant, silver-haired man who speaks fluent Arabic, English, Spanish, and French. In a cordial visit, which begins with his embracing Prince Hashel, Dr. Bilal quickly agrees to our request. Within an hour, the authorities are notified that two Americans would be arriving. No conditions or restrictions are imposed. The project has its green light.

The Road to al-Sukariya

We rent a car and hire a driver: a young, unshaven man named Qassem. He drives a dented car of a curious purple shade.

Speaking virtually no English except “yes” and “no,” Qassem is in need of diversion and slips a DVD into the front-mounted player of his car. He watches the Arab equivalent of MTV videos at 120 kilometers an hour. Occasionally, he takes his eyes off the undulating female dancers and the suave, mustachioed men to swerve away from oncoming Mercedes trucks.

The road to al-Sukariya is spare and beautiful. Dry scrub dots the arid landscape. Random olive groves rise inexplicably from the sand, far from any house or farm. The side of the road is mottled with encampments of ragged, patched and re-patched Bedouin tents.

A lone shepherd minds dozens of sheep, which nibble at the ground. Such nomads have wandered this area for centuries, passing through these expanses long before the Great Powers demarcated them as Iraq and Syria after World War I. Local tribesmen recognized no borders then, and the 375-mile border remains just as meaningless today.

We had discussed this issue earlier with Sheik Jawad al-Khalisi, head of the Iraqi National Foundation Congress, a coalition of Iraqi political parties opposed to Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. “The U.S. insists that Syria control its borders,” he said. “The U.S. can’t prevent drugs, arms, and human trafficking across its border with Mexico. So how can Syria, a much poorer country, be expected to do it?” (The U.S.–Mexico border is nearly 2,000 miles long.) Furthermore, he continued, the U.S. and Iraq governments were responsible for their side of the border. “You cannot control a border from one side,” he observed drily.

On the outskirts of Dayr al-Zawr city, we stop and pick up our translator, a young and very sharp English professor named Muhammad, who is a distant cousin of Nana’s. He is politically independent and scrupulous in his translations. After another hour of driving, Qassem yanks the wheel, and the car veers onto the road for al-Sukariya, a town of about 20,000. Even he is defeated by the gravel track, and the journey continues much more slowly, as we rock and sway over the rutted road as if we were riding a camel.

Financially well-off Syrians build farms on the outskirts of town. They are usually summer houses with small vegetable gardens or fruit trees surrounded by high concrete-block walls. We pull up to one such property—a few yards from the Euphrates River—a farm that is currently under construction. A 10-foot-high rectangle of walls encloses an area of hard-packed earth, perhaps 30 by 80 yards. The night watchman unlocks the chain fastening the iron gate and swings it open. The unused hinges shriek.

What Happened that Day

On that October Sunday, one year ago, the construction crew had been busy for several weeks, digging trenches and laying the foundation for a farmhouse. Rebar still poked up from the concrete. They had laid the concrete blocks to form 10-foot-high walls and hung heavy iron gates painted a deep plum color. A patched, Bedouin-style tent sat at one end of the farm, temporary home for night watchman Ali Ahman Ramadan, his wife, Suad al-Khalf, and their six-year-old son, Hassan. Workers regularly walked in and out of the tent, to eat or to seek shelter from the noonday sun. Perhaps from an aerial-reconnaissance perspective, people entering and exiting a tent looks suspicious.

At dusk, Suad al-Khalf sat on the bare floor of the tent while Hassan ran in and out. The weather was temperate and the sides of the tent flapped lightly. Five construction workers got ready to quit for the day: the foreman, Daud Mohammad Abdullah, and his four sons, Ibrahim, Thiab, Awad, and 16-year-old Faisal. At about 4:30 p.m., Ahmad Raka al-Khalifa, a neighbor, walked over to visit with the workers.

The men were laughing and relaxing after a hard day’s work when they heard helicopter engines overhead. Laughter turned to surprise, then panic. The helicopters rolled in, according to eyewitnesses, machine guns blazing away, drilling holes in the iron gate and concrete wall closest to the Euphrates. The machine guns and assault rifles fired so rapidly that the muzzles appeared to be shooting flames.

According to Suad al-Khalf, two helicopters landed inside the walls. (Another witness, Hamid, the mechanic, remembers seeing only one go in.) Dirt was blowing everywhere as soldiers leapt from the bellies of the aircraft. They quickly shot and killed the construction workers and the neighbor. “No one fired back because no one had weapons,” says al-Khalf, who, unaware of the level of carnage, stayed inside the tent and grabbed her son.

A U.S. soldier then entered the tent carrying an assault rifle. He looked at al-Khalf and Hassan and walked out. Another soldier followed moments later. He made a palm-down gesture with his hand—the universal signal for “do not move.” Al-Khalf did not. But the big man with the gun frightened Hassan, and he fled from the tent. Without thinking, his mother followed him outside. It was then that they shot her, and she fell to the ground, like the others lying along the walls.

Akram Hamid, a mechanic, was wounded by American soldiers on October 26, 2008. Photograph by Peter Coyote.

Hassan saw the red stains on the men’s tattered clothing. He turned and saw his mother too, outstretched by the tent, still moving, still breathing, but not answering his calls. Within 15 minutes of their landing, the helicopters and soldiers were gone. There was no one to help Hassan.

Two young men from a nearby farm had seen the helicopters and heard the firing. Muhammad and Ahmad al-Abed ran toward the farm until one of the helicopters fired a burst of machine-gun bullets in their direction. Neither was hurt, but they scurried for cover about 300 yards away.

Once the copters had pulled out for good, the two men ran into the farm, where they were the first to witness the six dead men, the dead teenage boy, and the seriously wounded Suad al-Khalf. Hassan stood above his mother. The police didn’t arrive for about 15 minutes.

“I recognized them,” Muhammad al-Abed says now, speaking of the dead. “All of them were workers here. I knew the father personally, but also knew other members of his family.” He doesn’t know if the Americans took any prisoners or bodies with them. With his mother nearby, Hassan later tells us, “There were many soldiers.” Asked if he knows where his father is, he replies, “He passed away. The Americans shot him.”

The Aftermath

It’s late afternoon as we drive to the hospital in al-Sukariya where the dead and wounded were taken after the raid. The coroner who administered to the victims, Dr. Aysar al-Fara, is a slight, precise man, wearing a nicely tailored, dark-blue Western suit. His mustache and nails are impeccably trimmed. He stares into the middle distance as he begins a ghastly and meticulous chronicle of the deaths. He speaks in a flat, clinical tone that one often expects from people for whom trauma is a way of life. “Each of the dead received between 10 and 15 bullets in the chest area,” he says. “None received less than 10. Also, each was shot once in the area of the navel.”

He speculates that they were shot by sharpshooters who were “seeking to snap the spine.” U.S.-military sources contacted later have never heard of such a practice. Special-ops troops are instructed to fire at the head and chest. So the stomach wounds remain a mystery. Dr. al-Fara is absolutely sure, however, that “the men were shot to be killed, the woman to be wounded.”

It is time to leave, but we have a last concern about Suad al-Khalf. The doctor who treated her had given her only a 50 percent chance of recovering. But after several operations in Damascus, she survived and returned to her home. When Dr. al-Fara treated her on October 26, she couldn’t explain what had happened. “She was hallucinating,” says Dr. al-Fara. “She kept saying, ‘Go, go, go, go,’ these four words over and over in English.” Those words, we speculate, may have been what the men from the helicopters were shouting as they went about their work.

Washington’s Version

In the days following the al-Sukariya incident, neither the Pentagon nor the Bush administration gave on-the-record explanations for the raid. Unnamed Pentagon officials leaked stories indicating the U.S. had killed al-Qaeda in Iraq leader Abu Ghadiya, but they offered scant details. When contacted for this article, a Pentagon official declined comment, refusing even to admit the U.S. conducted a raid. The eyewitness accounts and the reports from unidentified Department of Defense sources quoted early on by major media offer strong proof that the U.S. army attacked the farm in al-Sukariya. But had American soldiers killed a wanted terrorist or was the government now covering up a bungled raid?

Here’s what we know about Ghadiya from U.S.-government sources. Ghadiya was born Badran Turki Hishan al-Mazidih in Mosul, Iraq. The U.S. government isn’t clear about his birth date; estimates vary from 1977 to 1979. He was a close associate of the late al-Qaeda strategist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who was killed in an American air strike in 2006. Later Ghadiya worked for Abu Ayyub al-Masri, the current al-Qaeda in Iraq leader, and became a high-ranking leader of the terrorist organization, which formed after the 2003 U.S. invasion and has seemingly limited contact with the more famous al-Qaeda faction. In June 2006, Jordan reportedly sentenced Ghadiya to death in absentia for planning to attack that country with chemical weapons.

In February 2008, the Treasury Department issued a press release stating that Ghadiya ran the al-Qaeda in Iraq network in Syria, “which controls the flow of money, weapons, terrorists, and other resources through Syria into Iraq.” The Treasury Department identified Ghadiya, his brother, and two cousins as al-Qaeda terrorists. It said it would freeze any assets they might have under U.S. jurisdiction and prohibited U.S. companies from doing business with them.

But al-Qaeda in Iraq had already announced the death of Ghadiya in August 2006. Jihadist Web sites published his obituary, stating that he and a Saudi al-Qaeda operative had been killed in a U.S. rocket attack near the Iraqi-Saudi border.

One Syrian official says the U.S. never showed him any proof that Abu Ghadiya was alive after 2006, let alone smuggling jihadists across the border. Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Fayssal Mekdad says he also never saw evidence that Ghadiya had been killed in the al-Sukariya raid. The “[Bush] administration and its intelligence have always been wrong,” he tells us in an interview. Recalling a familiar talking point, he continues, “Remember the stories about the weapons of mass destruction in Iraq?”

In addition, the U.S. never produced any proof of Ghadiya’s death as it had after the assassinations of other high-ranking figures such as al-Qaeda in Iraq leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and Saddam Hussein’s sons, Uday and Qusay. (There are examples, however, in which the U.S. has claimed to have killed terrorists without releasing proof.) There have been no photos, eyewitness accounts, or captured computers, cell phones, or weapons. Furthermore, in a statement few close observers would argue with, Mekdad notes that Syria had nothing to gain from cooperating with groups such as al-Qaeda in Iraq. In fact, Syria has cooperated with the U.S. to combat such jihadist groups because they not only threaten Iraq but also have attacked Syria. Just before the raid, in September 2008, Sunni jihadists detonated a car bomb near a major shrine in Syria, killing 17 people and wounding 14 more.

The State Department and Pentagon spin the story very differently. Robert Malley, a special assistant for Arab-Israeli affairs to the president during the Clinton administration, and currently program director for the Middle East at the International Crisis Group, says that the Pentagon and State Department claimed they had actionable intelligence on a known terrorist at the site and took appropriate measures. Malley met with State Department officials in Washington one week after the raid. “They said they felt it was an unfortunate but necessary step,” he tells us, referring to the “collateral damage” caused by the attack. The raid, he says, killed Abu Ghadiya.

According to Malley, the action was carried out with approval from the Bush White House. He notes that on previous occasions, Syria hadn’t reacted to violations of its sovereignty, including Israel’s attack on an alleged nuclear facility near Dayr al-Zawr in 2007. “Syria didn’t change its diplomatic posture,” he says. “They still talked with the Israelis.” Did the White House believe Syria wouldn’t fight back in response to the al-Sukariya raid? “The administration believed the Syrians didn’t have many options, and they were too weak to respond.”

Army special-ops consultant Larry Johnson speculates that the U.S. took the terrorist leader’s body out in a helicopter. “In the case of a high-value target, they would take him back to get a DNA sample,” he says. As for claims by local Syrians to have known all the men, he notes that it wouldn’t be unusual for a terrorist cell to have a cover story. “If you asked Tony Soprano’s neighbors, they would tell you, ‘He’s a great guy. He’s in waste disposal.’”

Members of the al-Sukariya community, condemning America, gather near the coffins of the villages who died in the U.S. raid on October 26, 2008. By Hussein Malla/A.P. Images.

(Actually, Tony Soprano’s fictional neighbors knew what he did for a living.)

The community surrounding the farm knew the victims of the October 26, 2008 attack, according to Dr. al-Fara, the coroner, and the eyewitnesses we interviewed. Dr. al-Fara says emergency-room staff identified the dead from their papers. Friends and clansmen from the village also came to identify them. “None were strangers,” says Dr. al-Fara. “It was the end of the day. They were tired. You can tell from their clothes they were poor,” he recalls bitterly. He says that its inconceivable to him that the men were jihadists. “This was a criminal act.”

The explanation given by anonymous U.S.-government officials is “total bullshit,” exclaims Bob Baer, a C.I.A. field officer in the Middle East for 21 years, whose memoir, See No Evil, served as the basis for the film Syriana. Baer suspects that the intelligence on the raid was botched. “Where’s the body? Where are the documents or the cell phone? If they brought back an al-Qaeda body, why don’t they have something? There’s no conceivable way they would have killed him and not shown it.”

U.S. actions can be explained easily, according to Syrian political analyst Ahmad al-Dulemi. The Iraqi government forwarded inaccurate information about the al-Sukariya farm to U.S. forces, he argues. The U.S. was acting on faulty intelligence and bungled the raid.

Baer confirms that U.S.-military actions are currently carried out with far less diligence than in the past. “It used to be a Delta Force rule that you had to have eyes on your target for 24 hours in advance,” he says. Now “these raids are done in the dark. Since 9/11, you can act on fragmentary reports. If the C.I.A. says it got info from Iraqi sources, that’s enough.”

Congressman Nick Rahall, a Democrat from West Virginia who has traveled to the Middle East for 30 years to meet with leaders there, also concludes that the Bush administration mishandled the raid. Syrian civilians “lost their lives in an unfortunate attempt by the previous administration to once again mislead, bully, and isolate a regime,” he says in an interview from Washington. Such attacks across borders have a “disastrous effect on American foreign policy. They alienate civilians. The cowboy diplomacy of the past led America to some of its lowest [public-opinion] ratings around the world.”

At least one Syrian official is convinced that then vice president Dick Cheney and the neoconservative faction in the White House advocated the raid in an effort to derail future U.S.-Syria relations. That might explain Syria’s muted reaction to an attack that was, under international law, an act of war. Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Mekdad says Syria was in no condition to respond militarily against the much stronger U.S. He suggests that the Bush White House was interested in creating a roadblock for its successor.

“The neocons and their headmaster, Vice President Cheney, wanted to create problems so that a rapprochement between the [Obama] administration and Syria will be made more difficult,” he says. The Syrians decided to take their lumps and bide their time. That calculation may have paid off.

In 2004, the Bush administration had slapped Syria with economic sanctions and, in 2005, withdrawn its ambassador from Damascus. The Obama administration has taken a different tack, having sent four diplomatic and security missions to Syria and having agreed to re-install an ambassador, although no name or date has been announced.

The American public may not learn the full details of the al-Sukariya raid for some time, perhaps not until classified U.S.-government documents are released, years in the future. But the Arab world certainly believes the Syrian version of events, which contributes to growing anti-U.S. anger in the region. The perception that the U.S. launches raids and missile attacks without regard for civilian casualties is widespread in the region.

While the Obama administration doesn’t appear ready to attack Syria again, it has recently begun replicating similar tactics in Pakistan. Instead of helicopters and troops, the Pentagon is using unmanned drones controlled from the U.S. to fire missiles at suspected insurgents. Locals complain that the missiles frequently kill innocent civilians. Seventy-six percent of Pakistanis oppose such drone attacks, according to a public-opinion poll conducted by the International Republican Institute, a nonprofit loosely affiliated with the Republican Party and funded mostly by the U.S. government.

In Washington’s corridors of power, far from the battlefield, it may appear perfectly reasonable to attack countries that don’t or can’t stop terrorists. While national sovereignty is an important principle, the government argues, it must be weighed against clear and present threats to America. However, these cross-border incursions inevitably cause civilian deaths and exacerbate anger toward America.

Baer says Washington officials think they “have a monopoly on truth because we have the biggest military in the world.” When asked directly if he thinks that national sovereignty is an outmoded concept, he responds ironically, “That’s a very good argument. The fact that gangs in Los Angeles have taken over parts of L.A. certainly gives Mexico the right to invade. The police can’t control the area. Let the Mexican government send in the helicopters.”

During the long drive from al-Sukariya back to Damascus, we mull over what we’ve learned in the past eventful weeks. We are so engrossed that not even Qassem’s DVD-watching-while-driving arouses much anxiety.

We realize our own questions are shared by Middle Eastern countries and U.S. allies around the world. For them, it doesn’t matter if the al-Sukariya raid killed a terrorist or not. The salient point is that the Bush administration illegally crossed national borders and killed innocents. They want to know if the Obama administration will continue such policies or if America intends to commit its power and prestige to diplomacy and honest compromise. If not, will those who disagree with the administration in power find themselves targeted in America’s crosshairs, like the farmers of al-Sukariya?

The world watches and wonders, and so do we.

Freelance foreign correspondent Reese Erlich has covered the Middle East for 23 years and is the author of three books. His fourth, Conversations with Terrorists, will be published in September 2010. Peter Coyote has appeared as an actor in more than 130 films and television programs and is the author of numerous articles and the recently re-issued book Sleeping Where I Fall. He is currently working on a new book, Lies We Like to Believe, and three television pilots.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy