Back in May 2010, we ran an article Virtual Reality Combat Simulations as a Treatment for PTSD that resulted in a heated debate about both the negative and positive aspects of the Pentagon, and Department of Veteran’s Affairs experimentation with Virtual Reality War Simulations as a treatment for PTSD.

Among those contributing to that discussion in a dignified manner was Professor Skip Rizzo, Ph.D. Associate Director – Institute for Creative Technologies and Research Professor – Psychiatry and Gerontology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California.

In sum, readers can conclude that Skip is the Father (or Founder) of Virtual Reality (VR) as a treatment to help heal active-duty troops and Vets of PTSD. For the record, Dr. Rizzo and other proponents of VR, to treat PTSD, claim only that it is a TREATMENT not a cure for PTSD, and is to be used in conjunction with other treatments and therapies.

Our primary concern at VT is;

(1) that such treatments must be voluntary as opposed to mandatory, especially for active-duty troops, for the findings can too easily be skewed to conclude a Soldier or Marine is fit for follow on multiple deployments, and

(2) that VR is understood to be in developmental stages much as the use of Assistance Dogs and other innovative treatments for PTSD and not used as a smokescreen for a CURE to facilitate the denial of VA Claims for PTSD.

Regardless, below is the article we at VT have invited Skip to submit. It is entirely Skip’s views based on research. From this point on, we at VT have decided not to comment. It is kind of long, only because Skip has gone out of his way to get people to UNDERSTAND what his motives are, so we advise readers to jump or skim those parts they find most interesting.

ROBERT L. HANAFIN, Major, U.S. Air Force-Retired, VT

A Manifesto on Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress:

The Story of Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan and how it is helping some Service Members and Veterans to Heal the Invisible Wounds of War

by Skip Rizzo, Ph.D., Associate Director – Institute for Creative Technologies, Research Professor – Psychiatry and Gerontology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California. CONTACT: [email protected]

Table of Contents

1. A Lengthy, but Important Preamble to the Issues and Constraints of this Article

a. I am not a Veteran.

b. Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan is not a War GAME!

c. Not intended to be a “one size fits all” treatment for PTS

d. The focus of this work is on Combat-Related PTS

e. The issue of War Profiteering

f. The focus of the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan Project is on OIF/OEF, not Vietnam

g. The popular media and the politics of war

2. Links to Videos for those who do not want to read this lengthy article.

3. Introduction to the Problem (and what you already know)

4. How is PTSD defined by the DSM 4TR as a Clinical Disorder (and its limits)?

5. What is the “Exposure Therapy” Approach for PTS Treatment?

a. Recognition of Exposure Therapy’s Effectiveness

b. Theoretical Basis for Exposure Therapy

c. Exposure Therapy is NOT Brainwashing or what was used in “A Clockwork Orange”!

6. What is Virtual Reality and Why is it Being Used for Clinical Purposes?

a. The Vision of Clinical Virtual Reality

b. What is Virtual Reality Technology

c. Clinical Applications of Virtual Reality

7. A Brief Review of Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for PTS

a. Why use Virtual Reality for Exposure Therapy

b. Virtual Vietnam – The first use of VR for PTS Exposure Therapy

c. Virtual World Trade Center PTS Exposure Therapy

8. The Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan Exposure Therapy System – History, Graphic Content and Clinician Interface

a. A Brief History of the Development of Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan

b. A Detailed Description of the VR Scenarios

c. The Clinician’s Interface Control Panel

9. Clinical Research Results

10. Conclusions

a. Can VRET help Reduce the Stigma of Seeking Help and Break down Barriers to Care?

b. Will Digital Generation Service Members and Veterans be more likely to Seek Care with a Virtual Reality Treatment?

c. The Importance of Clinical Training

11. Future Directions and Potential Controversies

a. Assessment at the time of Recruitment

b. Stress Resilience Training Prior to Deployment

c. Post Deployment Assessment

d. Understanding the Brain and Biological Basis of PTS

12. Closing Thought

13. References

14. List of Sites that have the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan System

15. Author Bio

1. A Lengthy but Important Preamble to the Issues and Constraints of this Article

I would like to start off by thanking VT for providing me with this opportunity to present the work that we have been doing in the development of new Virtual Reality technology tools as a component in the treatment of combat-related Post-traumatic Stress (PTS).

I am sorry to say that this will be a long and detailed piece, but the problem area is so important and complex that it deserves this level of detail to ensure that it is accurately portrayed. A wise person once said, “For every complex problem, there is usually a simple answer…and it is usually wrong!” So please view the length and detail in this piece as a reflection of the complexity of the PTSD problem and the fact that I am not satisfied with easy and simple, yet, incorrect answers.

So first, before starting the article properly, I want to address some of the constraints that govern what will be presented in the article to follow. I will try to clearly and honestly explain how we have tried to acknowledge these constraints and our strategy for still making a positive contribution to this area in spite of them. But let’s get them up front here, right out of the gate:

a. I am not a Veteran. I recognize that in the eyes of many Vets, my personal lack of experience as a Military Veteran is thought to be a severe limitation in anything I might say or do in the creation of any treatment tool for combat-related PTS. In this regard, I have detailed in my bio what my experience and expertise in, and how that supports my efforts in this work. There are also strategies that we have in place that may mitigate that limitation.

We solicited feedback from active duty Service Member and Veteran populations in our initial virtual reality user testing and design and have members from these groups as partners on this project via their use of the tool in their roles as therapists and project leaders at the approximately 48 sites that have the system. We also solicit feedback from Service Members and Vets who have undergone the treatment as to ways that we can better address their needs.

I also want to note that in my career, I have developed successful Virtual Reality (VR) applications that have been used with a variety of clinical populations including Stroke, TBI, ADHD, Alzheimer’s Disease, etc. in spite of the fact that I have never had any of those conditions (well maybe I have selective ADHD according to my wife!).

From this, I have specialized expertise in applying technology to improve the tools used for clinical purposes and with that expertise, I chose to take on the PTS problem early in the OEF/OIF history (2003) since I saw that VR could potentially make a positive difference in the treatment of Service Members and Veterans.

With that said, I acknowledge that my lack of Vet credentials can be a limitation, and that is partly what has motivated my writing of this piece—I am aiming to present a clear, detailed and honest representation of this work and stand ready to hear ANY thoughtful feedback that can be helpful from a Vet perspective to improve the work!

This exchange of information could make a difference for the folks we are treating and I think I can assume that we are in agreement on this issue—we want to make a positive difference for those who have given all by way of their military service, and who are now suffering from the aftereffects of that service.

b. Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan is not a War GAME! The early development of the prototype of this therapy tool, Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan, did originally come from taking the graphic art from a section of the Xbox game, Full Spectrum Warrior. This was done since we had NO funding to start this project and needed a cheap way to start building the application in order to convince possible funders that this may be a useful method for treatment.

Even then, the initial prototype was NOT a GAME. We used game-type software and some of the art from the game, but we created a treatment tool using those assets as a start point and have since replaced most everything in the VR simulation based on our experience with OEF/OIF experienced persons (active duty and Vets).

Any gamer that has tried Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan is disappointed by the level of graphic realism compared to a 20million dollar budget video game and the fact that there is NO game interaction in the simulation. This can be actually seen in the comments by mostly gamers in response to a YouTube video called “Not a Game: Inside Virtual Iraq” which was posted by the author of an article that was published in The New Yorker magazine called simply “Virtual Iraq”.

That article presents a bit of history on the project, with the first interview with an OIF Vet treated with the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan system included, and you may perhaps want to check that out here:

So while the start of the work came from a game and uses game type software technology, it is a therapeutic simulation tool and is NOT A WAR GAME. Those who are familiar with and regularly play off-the-shelf war games should definitely see that.

c. The use of the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan system is not intended to be a “one size fits all” treatment for PTS. As many of the readers on this site might agree, PTS (or Posttraumatic Stress Injury as I am personally now favoring as a better, more useful descriptor, based on the writings of Figley and Nash (2006):

Combat Stress Injury (Psychosocial Stress Series)is a complex and multi-headed beast that defies any one definition or root cause.

Our approach, for better or worse, has been to address it as an “Anxiety Disorder”, as there was a lot of scientific evidence suggesting that many folks have benefited from treatments that were borne from that way of looking at the problem.

Our approach, for better or worse, has been to address it as an “Anxiety Disorder”, as there was a lot of scientific evidence suggesting that many folks have benefited from treatments that were borne from that way of looking at the problem.

Thus, the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan tool may not be of value for some, whose experiences are better considered with other conceptualizations. Moral Injury, Survivor Guilt, Societal Disregard, Dissociative Subtype (Lanius et al., 2010) and a long list of other descriptors apply here and the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan Exposure Therapy approach may not be effective for every ill and injury that Vets have faced from their experiences from the war, compounded by the bad hand they may have been dealt by society upon their return home.

But I am a scientist and clinician, and our team has given this approach our best shot from within a “classic” DSM Anxiety Disorder view (APA, 2000), in order to do some good for those who can be helped from this theoretical position.

d. The focus of this work is on Combat-Related PTS, not as a treatment for Sexual Assault during military service.

While sexual assault in theatre is a significant problem that deserves our best efforts, we have intentionally had to focus on one area that we could try to do well, and that is combat-related PTS.

We are doing other work with technology to train clinicians to do a better job of acknowledging and treating those who have PTS from sexual assault and a YouTube video of a 14-minute talk on that work, along with a description and demonstration of our other Wounds of War projects can be found here:

But, please keep in mind that the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan work was not designed to specifically address the sexual assault trauma challenges.

e. The Issue of War Profiteering.

This was an issue that came up in comments to the original article that came out on our work on this project, and I want to address it directly here. Yes, I have gotten about 10-15% of my salary covered specifically from my work designing, developing, evaluating and disseminating the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan exposure therapy application over the last few years (although in reality, I have put more than 100% effort on this work).

However, this is a not-for-profit clinical research effort (the software is freely available to anyone with training in exposure therapy as applied to military service members and Vets groups) and the rest of my salary at USC is covered from my other grant-funded work on other projects (Stroke/TBI rehab, Alzheimer’s Disease, childhood disorders, etc). I also purposely fought off any effort to have this system patented, as I saw that patenting could become an impediment to its free access to those who could benefit from its use.

However, in the interest of full disclosure, the project has an industry partner (mandated by the funders of this work), Virtually Better, Inc. that provides for a fee, the service of equipment purchase/delivery, set up, training, helpdesk support, updates, etc.

But I have NO financial relationship or ownership in this company and ANYONE who wants to buy their own equipment (and has the documented expertise in this form of exposure treatment) can get the software that we created for FREE.

Some centers have chosen this option and I have sent them the equipment manual with all the specs for equipment and set-up and the software so that they can provide this treatment in spite of limited resources within their group or agency (and have spent many unpaid hours with these folks walking them through the setup, operation, etc.).

So I am frankly repulsed at the false accusations that I have previously been subjected to on this site suggesting that I am a war profiteer. If there is a “profit” here, it comes in the form of personal satisfaction in the incremental successes of this work. And admittedly, my career as a recognized VR scientist has been advanced from this work, just as it has from any other positive effort that I have put into my work with other clinical populations.

But I have no spin-off company that is making money off of the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan work, in spite of the growing practice of some academics to move in that direction at the moment of the first positive report of clinical effectiveness. ‘Nuff Said on that one.

f. The focus of the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan Project is on OIF/OEF, not Vietnam.

Our collaborators on this project, however, include folks who have addressed Vietnam trauma and 9/11 World Trade Center trauma with Virtual Reality (Barbara Rothbaum/Larry Hodges-Virtual Vietnam; Joanne Difede/Hunter Hoffman-Virtual WTC).

I have posted a nine-minute piece on the use of Virtual Vietnam on YouTube that was done about 8 years ago for a documentary called “Virtually Healed” on the Discovery Health Channel that shows that work with commentary by Vietnam Vets about their experiences with the system.

I have also posted a video of the VR World Trade Center treatment that has a Fire Dept. patient (and Veteran) talking about his experience with this form of treatment.

Additionally, with all the interest generated by Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan PTS exposure therapy, it has rekindled an interest in the use of Virtual Vietnam with Veterans from that era. Here is a link to an article that includes the story of a Vietnam Vet undergoing this treatment that was posted in November 2009:

Madison.com: New therapy helps vets overcome PTSD

As a scientist studying the impact of stress on human wellbeing, I attempt to study the general processes common to all stressful events.

However, that scientific approach does NOT cast a blind eye to the unique differences that each type of traumatic experience may have on people. So, while I look for commonality across the human response to stress, I recognize that the experiences of Vietnam Vets will be different from those of Gulf War Vets and will be different from OEF/OIF experiences and will be different from 9/11 survivors and will be different from rape survivors and will be different from survivors of horrific motor vehicle accidents, and on and on across all events where a person can be emotionally injured by traumatic life experience.

Treatment should be of course tailored to the unique needs of the individual and the unique nature of their trauma. But, we do keep an eye out for the commonalities across all trauma, in order to better our understanding of these clinical problems, their impact, their time course and the ultimate aim of improving the lives of those who have suffered.

g. Finally, just a word on the popular media and the politics of war.

An online search of the various popular media reports on this work will yield many authors calling Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan a game, translating comments from an interview they had with me or a patient out of context, making outrageous claims of success from the initial data or just simply getting it all FUBAR’d.

In the previous article that Major Robert Hanafin posted, some of the content cited came from a well-meaning blogger who sat in the audience at a talk I gave at the Games for Health conference in 2006. What appeared in that blog, while well-meaning, was a somewhat inaccurate translation of much of what I presented, spun through the filter of a gamers’ agenda.

We all have AGENDA’s, but what I write in the following piece is the word from the horse’s mouth, not someone else’s interpretation of what I think or have done.

What follows is what I think about this Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan work and you can now respectfully crucify or applaud this effort in any way you see fit! I am comfortable with hearing all thoughts and concerns to try to drive this work to a better place to do some good, and that comfort comes partly from the fact that these will be MY words here that I will live with, and not someone else’s interpretation.

Also, the politics that are involved in this work seem to have been spotlighted at this site, based on commentaries that Dr. Sally Satel has made about Virtual Iraq.

I state here and again, that I have no association with this person and that in a free country, anyone has the right to say anything—for better or worse. However, her use of our work to endorse her agenda does not imply that we accept her agenda as support for our work! Her comments were based on HER ideas, NOT MINE! In this case, from what I read of her statements, she seems to have endorsed this work without ANY contact or discussion of this with ME!

You can tar me with the same brush as she may rightfully deserve to be tarred with for her choice to use Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan to endorse HER agenda, but I think this misrepresents the intent and purpose of our work to do something positive.

As I replied in the comments to the last article, I see this as the same “guilt by association” tactic as saying, “Hitler likes milk, therefore all dairy farmers are equally evil”.

With that said, I am not blind to how something created for a positive purpose, can be turned by others into something that could do great harm. That is certainly not mine or our Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan colleagues’ intentions, and so I look to the readers of this site to help us with your positive insights into how to be better vigilant for any sort of manipulation of the intent of our work. It is and has always been our intention to produce something in a manner that works for the potential needs and benefits of all Active Duty Service Members and Veterans of all eras, whether through direct care or in the generation of new knowledge.

Thus, I will stand by what I say here and welcome your honest thoughtful feedback for the purpose of doing a better job of it all. So fasten your seat belt—here we go!

2. Links to Videos for those who do not want to read this lengthy article.

Since some folks will not want to read this lengthy article but are still interested in this topic, here are links to videos that show how Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for PTS is conducted and testimonials from Active Duty and Veteran patients. All links are embedded in the titles.

- PTS Therapy Session at the Manhattan VA using Virtual Iraq:

- Army Reservist Discusses PTS Part 1.wmv:

- Army Reservist Discusses PTS Treatment with Virtual Iraq Part 2.wmv:

- Active Duty Marine discusses his PTS and Treatment with Virtual Iraq:

- National Guardsman Vet story on his PTS Treatment using Virtual Iraq:

- A 9-minute Virtual Vietnam Documentary video

- Virtual Reality used to treat PTS with World Trade Center Survivors:

- Virtual Reality used for acute pain reduction during wound care and physical therapy with an OIF Vet with severe burns:

Here are some YouTube links to video of some of the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan content.

- Early Virtual Iraq Prototype Video:

- Virtual USA-Mojave VR Exposure Therapy PTS Scenario:

- Virtual Iraq Exposure Therapy for PTS Bridge Attack:

- Virtual Iraq Exposure Therapy for PTS CityInterior:

- USC TEDx Talk and Demonstration by Marilyn Flynn and Skip Rizzo on Technology Applications to Address the Invisible Wounds of War (14 minutes):

3. Introduction to the Problem (and what you already know)

War is perhaps one of the most challenging situations that a human being can experience. The physical, emotional, cognitive and psychological demands of a combat environment place enormous stress on even the best-prepared military personnel. Since the start of the OEF/OIF conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, at least 1.6 million troops have been deployed. As of March 2009, there have been 4923 deaths and 33,856 Service Members wounded in action (Fischer, 2009).

Of the wounded in action (WIA), the total includes 935 major limb amputations and 351 minor amputations and as of 2008, traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been diagnosed in 43,779 patients (many of which are not included in the WIA statistics since mild TBI is often reported retrospectively, upon redeployment home). Moreover, the stressful experiences that are characteristic of the OIF/OEF warfighting environments have been seen to produce significant numbers of returning Service Members at risk for developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or if you prefer, for acquiring combat stress injuries (Figley & Nash, 2006).

In the first systematic study of OIF/OEF mental health problems, the results indicated that “…The percentage of study subjects whose responses met the screening criteria for major depression, generalized anxiety, or PTSD was significantly higher after duty in Iraq (15.6 to 17.1 percent) than after duty in Afghanistan (11.2 percent) or before deployment to Iraq (9.3 percent)” (Hoge et al., 2004).

Reports since that time on OIF/OEF PTS and psychosocial disorder rates suggest even higher incidence statistics (Fischer, 2009; Seal et al., 2007; Tanielian et al., 2008). For example, as of 2008, the Military Health System has recorded 39,365 active duty patients who have been diagnosed with PTSD (Fischer, 2009) and the Rand Analysis on PTSD (Tanielian et al., 2008) estimated that more than 300,000 active duty and discharged Veterans will suffer from the symptoms of PTSD and major depression.

These figures are heartbreaking and make a strong case for continued efforts at developing and enhancing the availability of evidence-based treatments to address a mental health care challenge that will have a significant impact on those suffering from these conditions and society as a whole for many years to come.

4. How is PTSD defined by the DSM 4TR as a Clinical Disorder (and its limits)?

As cited above, there are many ways that people have defined and conceptualized the type of emotional injury that can result from combat or other forms of trauma. None of the conceptualizations of this type of injury is fully agreed upon, nor can anyone of them fully capture the variance in the “what and why” that people feel following the experience of trauma.

The conceptualization that we operated from in the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan project is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (APA, 2000). Our view here is that this definition has wide acceptance in the clinical science community, although I believe that there are emotional injuries that occur following trauma that are not addressed in this conceptualization (i.e., moral injury, etc.).

In fact a recent pair of articles in the American Journal of Psychiatry discuss the problems and limitations of the DSM diagnosis (Chu, 2010; Lanius et al., 2010) and can be downloaded for free from here:

Chu: http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/167/6/615

Lanius et al: http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/abstract/167/6/640?ijkey=5c60a9c16c3f505fbbec090e7ba3163501c9faca&keytype2=tf_ipsecsha

One way to think about this decision to view PTS from this definition is in the old adage, “Do not mistake the map for the territory”. From that perspective, this definition was to be our map for embarking on this treatment approach with the recognition that we would find some new and uncharted territory along the way.

So in the DSM definition, the essential feature of PTSD is the development of characteristic symptoms following exposure to an extreme traumatic stressor involving the direct personal experience of an event that involves actual or threatened death or serious injury, or other threat to one’s physical integrity; or witnessing an event that involves death, injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of another person; or learning about unexpected or violent death, serious harm, or threat of death or injury experienced by a family member or other close associate.

Such incidents would be distressing to almost anyone and are usually experienced with intense fear, horror, and helplessness. Characteristic PTSD symptoms include intrusive thoughts, nightmares, and flashbacks, avoidance of reminders of the traumatic event, emotional numbing, and hyper-arousal.

Symptoms of PTSD are often intensified when the person is exposed to stimulus cues (or events in the world) that resemble or symbolize the original trauma in a non-therapeutic setting. Such uncontrolled cue exposure may lead the person to react with a survival mentality and mode of response. This definition and its history can be easily accessed from Wikipedia at:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Posttraumatic_stress_disorder#Diagnosis.

Again, this definition may not characterize all persons who have experienced combat-related emotional trauma, but it has general acceptance as a good start point to begin to address this challenge.

5. What is the “Exposure Therapy” Approach for PTS Treatment?

a. Recognition of Exposure Therapy’s Effectiveness

Among the many approaches that have been used to treat PTS, cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) with Exposure Therapy (ET) appears to have the best-documented therapeutic effectiveness (Bryant, 2005; Rothbaum, Meadows, Resick, et al., 2000; Rothbaum, Hodges, Ready, Graap & Alarcon, 2001; Rothbaum & Schwartz, 2002; Van Etten & Taylor, 1998). Expert treatment guidelines for PTS published for the first time in 1999 recommended that CBT with ET should be the first-line therapy for PTS (Foa, Davidson and Frances, 1999).

The comparative empirical support for exposure therapy was also recently documented in a review by the Institute of Medicine at the National Academies of Science of 53 studies of pharmaceuticals and 37 studies of psychotherapies used in PTS treatment (Institute of Medicine Committee on Treatment of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, 2007). The report concluded that, while there is not enough reliable evidence to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of most PTS treatments, there is sufficient evidence to conclude that CBT with an exposure therapy component is effective in treating people with PTS. This report can be freely downloaded in PDF format here:

http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2007/Treatment-of-PTSD-An-Assessment-of-The-Evidence.aspx

Now what is to follow may sound complicated, but please bear with me while I take a short paragraph to describe the theoretical basis for why exposure therapy is believed to work and then I will try to explain this in less “highfalutin” terms in the following paragraphs.

b. Theoretical Basis for Exposure Therapy

Exposure Therapy is a form of individual psychotherapy based on Foa and Kozak’s (1986) emotional processing theory, which states that PTSD involves pathological fear structures (that include the emotional memories of the traumatic experiences) that are activated when information represented in the structures is encountered (internal or external reminders of the trauma in everyday post-trauma life).

Successful treatment requires emotional processing of the fear structures in order to modify their pathological elements so that the stimuli no longer invoke fear or anxiety. Emotional processing first requires accessing and activating the fear/anxiety structure associated with the traumatic event and then incorporating new information that is not compatible with it.

Imaginal Exposure Therapy entails engaging mentally with the fear structure through repeatedly revisiting the traumatic event in imagination but within a safe environment. In practice, a person with PTS typically is guided and encouraged by the clinician to gradually imagine, narrate and emotionally process the traumatic event within the safe and supportive environment of the clinician’s office.

This approach is believed to provide a low-threat context where the patient can begin to therapeutically process the emotions that are relevant to the traumatic events as well as de-condition the learning cycle of the disorder via a process called extinction learning. This is not about erasing painful memories, but rather making it such that that the pain of a traumatic memory becomes more manageable through a therapeutic exposure approach.

Persistent efforts to avoid talking about or emotionally processing hard and painful memories is thought to reinforce avoidance by providing temporary relief and becomes an unhealthy pattern for maintaining the recurrence of painful emotional responses, or chronic PTSD. In short, by avoiding thoughts or situations that remind the PTS sufferer of the trauma, a sense of temporary relief is achieved and that serves to perpetuate and encourage future avoidance. That relief from avoidance is short-lived and believed to NOT support healthy adjustment in the long run.

Now, I know that readers may read this and say, I live this horror every day of my life, why haven’t I experienced this alleged extinction process? Many people who experience trauma feel the pain of loss and violation for a long time after trauma. And while that pain never completely disappears, for many people, the pain becomes easier to bear such that they do not experience the pain at the same level, many months later, that they experienced during the time immediately after the trauma.

These individuals, while still bearing the scars of their trauma experience, eventually process and manage the painful memories and the extreme emotional response is thought to diminish due to this extinction learning process. According to this model, when PTS occurs, it is believed to result (for whatever reason) from a failure of this natural extinction process.

Whether it is due to the extreme nature of the trauma or the way a person thinks about the trauma, this extinction process does not always occur naturally and when that happens, these are the people that are often labeled as “chronic PTSD”. There has been a lot of research as to the brain and biological factors that may cause this to happen in people. Considerable work has found neural circuits in the limbic system and the frontal lobe regions of the brain that are affected in some people, more than others when they are exposed to traumatic stressors.

What ET attempts to do is, in a very gradual and systematic way, use the reminders of the trauma as the “mental battleground” to begin to foster this extinction or habituation process in ways that did not occur for the person naturally in everyday life.

For those who do not gradually get better over time naturally after the experience of extreme stress, ET is an effort to therapeutically “jumpstart” that process, by having the person imagine the event and talk about it as if it is happening now from a first-person perspective with the support of a well-trained clinician that knows when to push the person and when to back off.

This is not an easy process and some have referred to it as “hard medicine for a hard problem”. Gains are seen slowly, but overall, with persistence, it has been shown to be effective with many PTS sufferers.

When someone is treated by giving them drugs to generally reduce or avoid the experience of anxiety, it may work temporarily, but it does not promote the confrontation of the fear or anxiety feelings that is required to produce this extinction learning and emotional processing that leads to better coping.

VR simulations are thought to enhance the conduct of ET because it prevents the avoidance of the hard trauma memories beyond what most folks are capable of by using imagination alone. However, not being a Vietnam Vet, I cannot begin to fathom the pain of the emotional injuries that you have carried all these years (compounded in many ways over the years by societal disregard or worse!).

But to give up and say it is too late to change things for Vietnam Vets, strikes me as a pessimistic and hopeless way of looking at this problem, and so that is why the ET approach, as counter-intuitive as it may seem at first, appeals to me as a way to make a difference for treatment with this group as well as with OIF/OEF Vets. And that is what drives most clinicians in this area—the hope that things can be changed and people can reclaim their emotional life with less pain.

For those interested in learning more about Exposure Therapy, this link provides a brief description of exposure therapy being used at the Defense Center of Excellence:

And, as an aside, the clinical scientist who is acknowledged as the person responsible for laying down the foundation for the use of Exposure Therapy, Dr. Edna Foa, was recently recognized in Time Magazine’s 2010 Top 100 Influential People. For the story at “Truth for Troops” go to:

http://truthfortroops.blogspot.com/2010/04/edna-foa-in-times-2010-top-100.html

c. Exposure Therapy is NOT Brainwashing or what was used in “Clockwork Orange”!

I also want to counter a claim here that has been leveled at Exposure Therapy (and at myself too) by some who say that this is brainwashing and akin to a “Clockwork Orange” approach. As appealing as that may be to say when you have spent decades being pissed off at the shoddy level of respect and care that you have received, Clockwork Orange is no roadmap for what ET is about.

In Clockwork Orange, the Malcolm McDowell character was forcibly made to view violent imagery while being given a drug that made him violently ill, in order to condition him to be non-violent by creating an association between violence and the experience of painful nausea/sickness. This “aversive conditioning” approach bears no resemblance to what exposure therapy attempts to do.

ET attempts to help the person confront and process their traumatic memories in a supportive environment, such that over time, they are better able to handle painful trauma memories by way of this extinction process. Yes, learning new ways to respond and react is common to both approaches, but by very different means and for very different purposes.

And I would go further to say that ANY treatment for emotional wounds or issues, really at its core, is about changing how people think about events in their life. The focus here is to help people go on with their lives in ways that support their health, happiness, and adaptation to future challenges, and not about using some mind control process just to shut them up!

Related to this, I have heard people refer to their experience of pharmacological treatments for PTS as “chemical lobotomies”. The ET approach is the exact opposite of that treatment as well, as its goal is to help people better deal with what has come before in order to be better equipped for what is still to come—it is not about further “numbing” the person to make them more “manageable”.

So if you are still with me here, that is the basis for exposure therapy for PTS. Nothing in life is 100%, but the research so far supports ET as a safe, evidence-based treatment, and I believe it is worth the effort to follow this path in my own research to make it more effective through the use of VR simulations to engage PTS sufferers in this hopeful process. Now I will move on to a brief explanation as to what is Virtual Reality, and describe what Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan is and present some results of research to date using it with OEF/OIF Service Members and Vets.

6. What is Virtual Reality and Why is it being used for Clinical Purposes?

a. The Vision of Clinical Virtual Reality

Over the last 15 years, a revolution has occurred in the development of Virtual Reality (VR) systems for enhancing clinical practice and research. Technological advances in the areas of computation speed and power, graphics and image rendering, display systems, tracking, interface technology, authoring software, and artificial intelligence have supported the creation of low-cost and usable PC-based VR systems.

As well, a determined and expanding group of researchers and clinicians have not only recognized the potential impact of VR technology but have now generated significant research literature that documents the many clinical targets where VR can add value over traditional assessment and intervention approaches (Holden, 2005; Parsons & Rizzo, 2008a; Powers & Emmelkamp, 2008; Rose, Brooks & Rizzo, 2005; Riva, 2005).

This convergence of the exponential advances in underlying VR enabling technologies with a growing body of clinical research and experience has fueled the evolution of the discipline of Clinical Virtual Reality. And this state of affairs now stands to transform the vision of future clinical practice and research in the disciplines of psychology, medicine, neuroscience, physical and occupational therapy, and in the many allied health fields that address the therapeutic needs of those with clinical disorders.

b. What is Virtual Reality Technology

In its basic form, VR can be viewed as an advanced form of human-computer interface that allows the user to “interact” with and become “immersed” within a computer-generated simulated environment. VR sensory stimuli can be delivered by using various forms of visual display technology that integrates real-time computer graphics and/or photographic images/video with a variety of other sensory output devices that can present audio (earphones), “force-feedback” haptic/touch sensations and even olfactory (smell) content to the user.

An engaged interaction with a virtual experience can be supported by employing specialized tracking technology that senses the user’s position and movement and uses that information to update the visual, audio and haptic/touch stimuli presented to the user to create the illusion of being immersed “in” a virtual space in which they can interact.

One common configuration employs a combination of a head-mounted display (HMD) and a tracking system that allows the delivery of computer-generated images and sounds of a simulated virtual scene that corresponds to what the individual would see and hear if the scene were real.

Other methods employ 3D displays that project on a single wall or on multiple wall space (multi-wall rooms are known as CAVES). As well, basic flatscreen display monitors have been used to deliver interactive VR scenarios that, while not immersive, are sometimes sufficient, cost-effective options for delivering testing, training, treatment and rehabilitative applications using VR.

c. Clinical Virtual Reality Applications

The unique match between VR technology assets and the needs of various clinical treatment approaches has been recognized by a number of authors and an encouraging body of research has emerged, particularly in the area of exposure therapy for anxiety disorders (Glantz, Rizzo & Graap, 2003; Parsons & Rizzo, 2008; Powers and Emmelkamp, 2008; Rizzo, Schultheis, Kerns & Mateer, 2004; Rothbaum, et al., 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002; Zimand et al., 2003, Difede & Hoffman, 2002).

Whereas in the mid-’90s VR was generally seen as “a hammer looking for a nail”, it soon became apparent to some scientists in both the engineering and clinical communities, that VR could bring something to clinical care that wasn’t possible before its advent. By its nature, VR simulation technology is well suited to simulate the challenges that people face in naturalistic environments and consequently can provide objective simulations that are useful for clinical assessment and treatment purposes.

The capacity of VR technology to create controllable, multisensory, interactive 3D stimulus environments, within which human behavior could be motivated and measured, offered clinical assessment and treatment options that were not possible using traditional methods. As well, a long and rich history of encouraging findings from the aviation simulation literature lent support to the concept that testing, training, and treatment in highly proceduralized VR simulation environments would be a useful direction for psychology and rehabilitation to explore. Much like an aircraft simulator serves to test and train piloting ability under a variety of controlled conditions, VR could be used to create relevant simulated environments where assessment and treatment of cognitive, emotional and motor problems could take place.

A shortlist of areas where Clinical VR has been usefully applied includes fear reduction in persons with simple phobias (Parsons et al., 2008; Powers et al., 2008), treatment for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (Rothbaum et al., 2001; Difede & Hoffman, 2002; Difede et al., 2007; Rizzo et al., 2009), stress management in cancer patients (Schneider et al., 2004), acute pain reduction during wound care and physical therapy with burn patients (Hoffman et al., 2004)

body image disturbances in patients with eating disorders (Riva, 2005), navigation and spatial training in children and adults with motor impairments (Stanton et al., 1998; Rizzo et al., 2004), functional skill training and motor rehabilitation with patients having central nervous system dysfunction (e.g., stroke, TBI, SCI cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, etc.) (Holden, 2005; Weiss et al., in press), and for the assessment and rehabilitation of attention, memory, spatial skills and other cognitive functions in both clinical and unimpaired populations (Rose et al., 2005; Rizzo & Kim, 2005).

To do this, VR scientists have constructed virtual airplanes, skyscrapers, spiders, battlefields, social settings, beaches, fantasy worlds and the mundane (but highly relevant) functional environments of the schoolroom, office, home, street, and supermarket. In essence, clinicians can now create simulated environments that mimic the outside world and use them in the treatment setting to immerse patients in simulations that support the aims and mechanics of a specific therapeutic approach.

Concurrent with the emerging acknowledgment of the unique value of Clinical VR by scientists and clinicians, has come a growing awareness of its potential relevance and impact by the general public. While much of this recognition may be due to the high visibility of digital 3D games, the Nintendo Wii, and massive shared internet-based virtual worlds (World of Warcraft, Halo and 2nd Life), the public consciousness is also routinely exposed to popular media reports on clinical and research VR applications.

Whether this should be viewed as “hype” or “help” to a field that has had a storied history of alternating periods of public enchantment and disregard, still remains to be seen. Regardless, growing public awareness coupled with the solid scientific results has brought the field of Clinical VR past the point where skeptics can be taken seriously when they characterize VR as a “fad technology”.

However, while Clinical VR has been advanced by Video Game technologies, VR simulations for clinical purposes are NOT Games. With Clinical VR simulations, the stimuli and events in the world are carefully delivered in a fashion to promote an experience that is theoretically believed to produce a therapeutic outcome/goal, rather than based on the defined steps for winning or beating a game challenge for the purpose of entertainment. While we may use game features to motivate interaction (particularly with VR game-based applications to motivate and inspire physical therapy after a stroke or a TBI), this is not how a VR simulation is used for PTS exposure therapy.

This will be more clear in the next section, but although the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan prototype simulations may have originally used art and technical assets from a game (Full Spectrum Warrior), as it is now developed and used, it is NOT a War GAME!

7. A Brief Review of Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for PTS

a. Why use Virtual Reality for Exposure Therapy

While the benefit of imaginal exposure therapy has been established in multiple studies with diverse trauma populations, many patients are unwilling or unable to effectively visualize the traumatic event. This is a crucial concern since avoidance of cues and reminders of the trauma is one of the cardinal symptoms of the DSM diagnosis of PTSD. In fact, research on this aspect of PTS treatment suggests that the inability to emotionally engage (in imagination) is a predictor for negative treatment outcomes (Jaycox, Foa, & Morral, 1998).

To address this problem, researchers have recently turned to the use of Virtual Reality (VR) to deliver exposure therapy (VRET) by immersing patients in simulations of trauma-relevant environments in which the emotional intensity of the scenes can be precisely controlled by the clinician in collaboration with the patients’ wishes. In this fashion, VRET offers a way to circumvent the natural avoidance tendency by directly delivering multi-sensory and context-relevant cues that evoke the trauma without demanding that the patient actively try to access his/her experience through effortful memory retrieval.

Within a VR environment, the hidden world of the patient’s imagination is not exclusively relied upon and VRET may also offer an appealing, non-traditional treatment approach that is perceived with less stigma by “digital generation” Service Members and Veterans who may be reluctant to seek out what they perceive as traditional talk therapies.

b. Virtual Vietnam – The first use of Virtual Reality for PTSD Exposure Therapy

The first effort to apply VRET began in 1997 when researchers at Georgia Tech and Emory University began testing the Virtual Vietnam VR scenario with Vietnam Veterans diagnosed with PTS. This occurred over 20 years after the end of the Vietnam War. During those intervening years, in spite of valiant efforts to develop and apply traditional psychotherapeutic and pharmacological treatment approaches to PTS, the progression of the disorder in some Veterans significantly impacted their psychological well-being, functional abilities and quality of life, as well as that of their families and friends.

This initial effort by Barbara Rothbaum and Larry Hodges (also collaborators on the current Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan project) yielded encouraging results in a case study of a 50-year-old, male Vietnam veteran meeting DSM criteria for PTS (Rothbaum et al., 1999). Results indicated post-treatment improvement on all measures of PTS and maintenance of these gains at a 6-month follow-up; with a 34% decrease in clinician-rated symptoms of PTS and a 45% decrease in self-reported symptoms of PTS.

This case study was followed by an open clinical trial with Vietnam Veterans (Rothbaum et al., 1999). In this study, 16 male Veterans with PTS were exposed to two head-mounted display-delivered virtual environments, a virtual clearing surrounded by jungle scenery and a virtual Huey helicopter, in which the therapist controlled various visual and auditory effects (e.g. rockets, explosions, day/night, shouting).

After an average of 13 exposure therapy sessions over 5-7 weeks, there was a significant reduction in PTSD and related symptoms. For more information, see the 9-minute Virtual Vietnam Documentary video at:

c. Virtual World Trade Center PTSD Exposure Therapy

Similar positive results were reported by Difede & Hoffman (2002) for PTSD that resulted from the attack on the World Trade Center in a case study using VRET with a patient who had failed to improve with traditional exposure therapy (JoAnn Difede is also a collaborator on the current Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan project).

This group has since reported positive results from a waiting list controlled study using the same VR World Trade Center application (Difede et al., 2007). The VR group demonstrated statistically and clinically significant decreases on the “gold standard” Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) relative to both pre-treatment and to the wait-list control group with a between-groups post-treatment effect size of 1.54 (which is very large for this kind of work).

Seven of 10 people in the VR group no longer carried the diagnosis of PTSD, while all of the wait-list controls retained the diagnosis following the waiting period and treatment gains were maintained at 6-month follow-up. Also noteworthy was the finding that five successful patients of the 10 people in the VR group had previously participated in imaginal exposure treatment with no clinical benefit.

Such initial results were encouraging and suggested again that VR may be a useful component within a comprehensive treatment approach for persons with combat/terrorist attack-related

PTSD. For more information, see the Virtual World Trade Center video at:

8. The Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan Exposure Therapy System – History, Graphic Content and Clinician Interface

a. A Brief History of the Development of Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan

In 2004, the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT), in collaboration with the many colleagues (Rothbaum, Difede, Reger, Pair, Graap, Mclay, Spitalnick, Newman, Parsons, Buckwalter and too many others to mention here), partnered on this project funded by the Office of Naval Research (ONR) to develop a series of VR exposure therapy (VRET) environments known at the time as Virtual Iraq. The initial prototype system was constructed by recycling virtual art assets that were originally designed for the commercially successful X-Box game and U.S. Army-funded combat tactical simulation trainer, Full Spectrum Warrior.

Early Virtual Iraq Prototype Video:

The first Virtual Iraq prototype was then continually evolved with newly created art and technology assets available to ICT in a process that was highly informed by feedback from clinicians, active duty Service Members and Vets with combat experience in Iraq and Afghanistan.

These pre-clinical tests were conducted at the Naval Medical Center–San Diego, within an Army Combat Stress Control Team in Iraq (see Figure 1), Camp Pendleton and at Madigan Army Medical Center at Ft. Lewis. As well, we have had over 300 active duty Service Members and Vets visit our USC lab to try the system and share their advice on its design and development.

This expert feedback was essential for informing the development of the VR combat scenarios and allowed us to go beyond what would have been possible to imagine from the “Ivory Tower” of the academic world.

Over the years, the system has expanded to include a USA Desert Driving scenario and an Afghan-themed environment to supplement the Iraq Desert and City scenarios. From this evolution, there is no longer any of the original Full Spectrum Warrior content in this therapeutic VR simulation.

The current Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan system application consists of these generic virtual scenarios designed to represent relevant contexts for the conduct of VR exposure therapy. In addition to the visual stimuli presented in the VR, head-mounted display–directional 3D audio, vibrotactile and smell stimuli of relevance can be delivered into the simulation. Stimulus presentation is controlled by the clinician via a separate “wizard of oz” interface, with the clinician in full audio contact with the patient.

Figure 1. User-Centered Feedback from Active Duty Service Members in Iraq (photos courtesy of Cpt. Greg Reger (Ret.))

Figure 1. User-Centered Feedback from Active Duty Service Members in Iraq (photos courtesy of Cpt. Greg Reger (Ret.))

b. A Detailed Description of the VR Scenarios

The 24 square block “City” setting has a variety of elements including a marketplace, desolate streets, checkpoints, ramshackle buildings, warehouses, mosques, shops and dirt lots strewn with junk (see Figure 2). Access to building interiors and rooftops is available and the backdrop surrounding the navigable exposure zone creates the illusion of being embedded within a section of a sprawling densely populated desert city.

Vehicles are active in streets and animated virtual pedestrians (civilian and military) can be added or removed from the scenes. The software has been designed such that users can be “teleported” to specific locations within the city, based on a determination as to which areas of the environment most closely match the patient’s needs, relevant to their individual trauma-related experiences.

Video of Virtual Iraq Exposure Therapy for PTSD City Interior:

Figure 2. Scene from Virtual Iraq City

Figure 3. Desert Road HUMVEE interior

Figure 4. Desert Road Checkpoint

Figure 5. Night Vision Setting

The “Desert Road” scenario consists of a roadway through an expansive desert area with sand dunes, occasional areas of vegetation, intact and broken-down structures, bridges, battle wreckage, a checkpoint, debris, and virtual human figures (see Figures 3 & 4). The user is positioned inside of a HUMVEE that supports the perception of travel within a convoy or as a lone vehicle with selectable positions as a driver, passenger or from the more exposed turret position above the roof of the vehicle.

The number of soldiers in the cab of the HUMVEE can also be varied as well as their capacity to become wounded during certain attack scenarios (e.g., IEDs, rooftop/bridge attacks). A Virtual USA-Mojave scenario was built as an initial first step for patients to get used to the system and as sort of a “toe in the water” for starting the process of exposure therapy.

- Video of Virtual Mojave VR Exposure Therapy PTSD Scenario

- Video of Virtual Iraq Exposure Therapy for PTSD Bridge Attack

A Virtual Afghanistan version of the system was created by modifying the terrain, architecture and general design (see Figures 9 & 10) to make the content relevant for use with service members with deployment experience in that combat theatre. New funding recently approved by the Army and the Air Force will expand the Afghan content and develop scenarios that are specifically relevant for combat medics.

Figures 6 & 7. Scenes from Virtual Afghanistan HUMVEE Turret Position

Figures 6 & 7. Scenes from Virtual Afghanistan HUMVEE Turret Position

Both the city and desert road HUMVEE scenarios are adjustable for time of day or night, weather conditions, illumination, night vision (see Figure 5) and ambient sound (wind, motors, city noise, prayer call, etc.). Users can navigate in both scenarios via the use of a standard gamepad controller, although we have recently added the option for a replica M4 weapon with a “thumb-mouse” controller that supports movement during the city foot patrol.

This was based on repeated requests from Iraq/Afghan experienced Service Members and Vets who provided frank feedback indicating that to walk within such a setting without a weapon in-hand was completely unnatural and distracting!

However, unlike off the shelf “War Games,” there is no option for firing a weapon within the VR scenarios. It is our firm belief that the principles of exposure therapy are incompatible with the cathartic acting out of revenge fantasy that a responsive weapon might encourage.

Also, one other thing to note here and that is that while the graphics are not an exact replica of reality, research shows that it doesn’t have to be in order to engage users and produce a good therapeutic effect.

It is a delicate balance to create graphic scenes that are credible enough to assist a person in the activity of processing difficult emotional memories without being too much like an off the shelf War Game.

What has been found in previous work with Virtual Vietnam, Virtual World Trade Center and now with the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan work, is that by making the visual scenes a bit vaguer, it leaves enough “room” for the user to access elements of their own unique memories. We are trying to help people process difficult personal memories, and a too-detailed graphic environment may be more of a distraction from that personalized experience.

Remember—the aim is for people in the simulation to narrate their own personal experience in the first person, while immersed in the VR environment, rather than to passively look around at the scenes. Most users report that we have hit this balance in a useful manner for that purpose and new funding to rebuild Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan with more current software (to replace the 2004 code it uses now) will focus more on creating more diverse scenes and content, rather than making it look like a commercial war game.

c. The Clinician’s Interface Control Panel

Figure 8 Clinician’s Interface

The presentation of additive, combat-relevant stimuli into the VR scenarios can be controlled in real-time via a separate “Wizard of Oz” clinician’s interface (see Figure 6), while the clinician is in full audio contact with the patient. This control panel is a key tool that provides a clinician with the capacity to customize the virtual experience to the individual therapeutic needs of the patient.

This interface allows a clinician to place the patient in VR scenario locations that resemble the setting in which the trauma-relevant events occurred and ambient light and sound conditions can be modified to match the patients narrated description of their experience. The clinician can then gradually introduce and control real-time trigger stimuli (visual, auditory, olfactory and tactile), via the clinician’s interface, as required to foster the anxiety modulation needed for extinction, therapeutic habituation, and emotional processing in a customized fashion according to the patient’s past experience and treatment progress.

9. Clinical Research Results

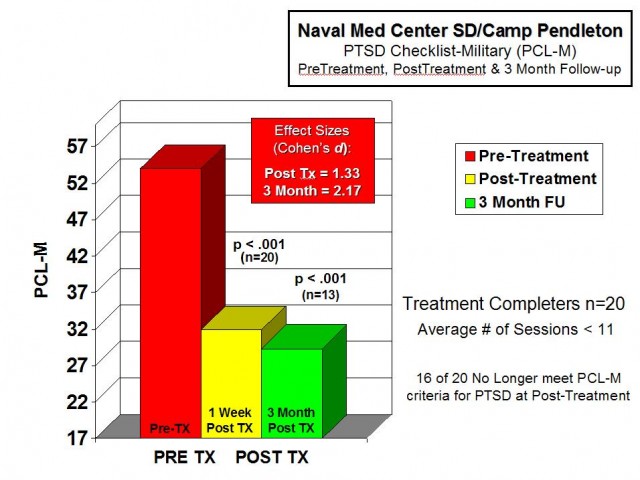

Figure 9. Mean PTSD Checklist scores across treatment

Leading up to the first clinical group test of treatment effectiveness, some usability studies and case study reports were published with positive findings in terms of Service Members and Vets acceptance, interest in the treatment, and clinical successes (Gerardi et al., 2008; Holloway et al., 2009; Reger et al., 2009; Reger & Gahm, 2008; Wilson et al., 2008). The Office of Naval Research, who had funded the initial system development of Virtual Iraq, also supported an initial clinical trial to evaluate the feasibility of using VRET with active duty participants.

The study participants were recently redeployed from Iraq/Afghanistan and had engaged in previous PTSD treatments (e.g., group counseling, EMDR, medication, etc.) without benefit. The standard treatment protocol consisted of 2X weekly, 90-120 minute sessions over five weeks that also included physiological monitoring (Heartrate, Galvanic Skin Response, and Respiration) as part of the data collection.

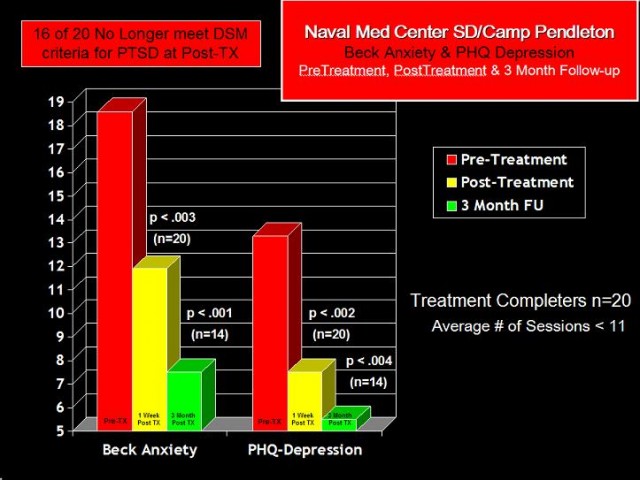

The VRET exposure exercises followed the principles of exposure therapy (Foa et al., 1999) and the pace was individualized and patient-driven. The clinical measures used were the PTSD Checklist-Military Version (PCL-M), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and Patient Health Questionnaire-Depression (PHQ-9).

Analysis of the first 20 active duty service members to complete treatment (19 male, 1 female, Mean Age=28.1) have indicated positive clinical outcomes. For this sample, mean pre/post-PCL-M scores decreased; Mean values went from 54.4 to 35.6. Paired pre/post-t-test analysis showed these differences to be statistically and clinically significant (t=5.99, df=19, p < .001). Correcting for the PCL-M no-symptom baseline of 17 indicated a 50% decrease in symptoms and 16 of the 20 completers no longer met PCL-M criteria for PTSD at posttreatment.

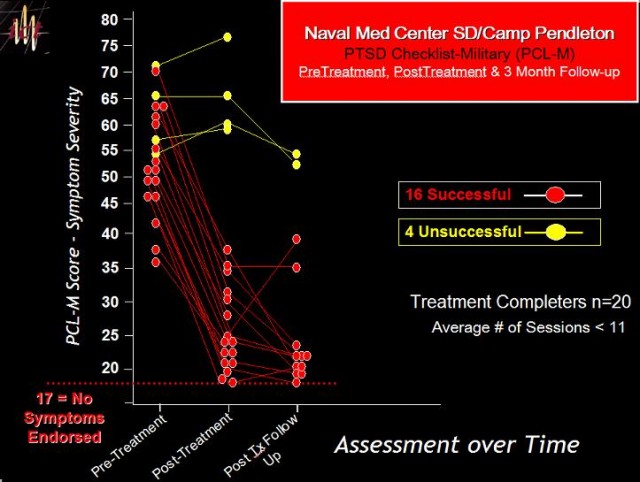

Group averages and individual participant scores at baseline, post-treatment, and 3-month follow-up are in Figures 11-12. For this same group, mean BAI (anxiety) scores significantly decreased 33% from 18.6 to 11.9, (t=3.37, df=19, p > 0.003) and mean PHQ-9 (depression) scores decreased nearly 50% from 13.3 to 7.15, (t=3.68, df=19, p < 0.002). These results are graphed in Figure 13 and were also found to be both statistically and clinically significant.

The average number of sessions for this sample was just under 11. Also, two of the successful treatment completers had documented mild and moderate traumatic brain injuries, which provide an early indication that this form of exposure therapy can be useful (and beneficial) for this population.

Figure 10. Individual PTSD Checklist scores across treatment

Figure 10. Individual PTSD Checklist scores across treatment

Other studies are also reporting positive outcomes. A recent study with active-duty soldiers from Ft. Lewis compared VRET with a Cognitive Behavioral Group approach and the results showed that VRET produced more effective clinical outcomes than the group therapy approach. (Reger et al., in press). And two case reports indicating positive outcomes using this system have been also published (Gerardi et al., 2008; Reger and Gahm, 2008).

Currently, there are at least three Randomized Controlled Trials that are ongoing with this system with AD and Veteran populations and other non-treatment focused studies are underway. This research has been supported by the relatively quick adoption of this approach by approximately 48 Military, VA and University clinic sites (locations listed at end of the article).

Figure 11. Beck Anxiety Inventory and PHQ-Depression scores across treatment

Figure 11. Beck Anxiety Inventory and PHQ-Depression scores across treatment

*Here are links to videos that show how this therapy is conducted and 3 testimonials from Active Duty and Veteran patients.

- PTSD Therapy Session at the Manhattan VA using Virtual Iraq

- Active Duty Marine discusses his PTSD and Treatment with Virtual Iraq

- National Guardsman Vet profiled on his PTSD Treatment using Virtual Iraq

- Army Reservist Discusses PTSD Part 1.wmv

- Army Reservist Discusses PTSD Treatment with Virtual Iraq Part 2.wmv

10. Conclusions

Results from uncontrolled trials and case reports are difficult to generalize from and we are cautious not to make excessive claims based on these early results. However, using accepted diagnostic measures, 80% of the treatment completers in our initial VRET sample showed both statistically and clinically meaningful reductions in PTSD, anxiety and depression symptoms, and anecdotal evidence from patient reports suggested that they saw improvements in their everyday life situations. These improvements were also maintained at three-month post-treatment follow-up.

Based on our initial open clinical trial and similar results from other research groups, we are encouraged by these early successes and continue to gather feedback from patients regarding the therapy and the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan environments. The system is currently being updated with added functionality that has its design “roots” from feedback acquired from these initial patients and the clinicians who have used the system thus far.

These findings will be used to develop, explore and test hypotheses as to how we can improve treatment and also determine what patient characteristics may predict who will complete and benefit from VRET and who may be best served by other approaches. This clinical treatment and research will now continue in partnership with the 48 Military, Veteran and University clinics locations that now have the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan exposure therapy system.

This work will also address a series of clinical research questions that are aimed to improve PTS treatment.

a. Can VRET help Reduce the Stigma of Seeking Help and Break down Barriers to Care?

Research suggests that there is an urgent need to reduce the stigma of seeking mental health treatment in active duty Service Members and Veteran populations. One of the more foreboding findings in the early Hoge et al., (2004) report, was the observation that among Iraq/Afghanistan War veterans, “…those whose responses were positive for a mental disorder, only 23 to 40 percent sought mental health care.

Those whose responses were positive for a mental disorder were twice as likely as those whose responses were negative to report a concern about possible stigmatization and other barriers to seeking mental health care.” (p. 13). While US military training methodology has better-prepared soldiers for combat in recent years, such hesitancy to seek treatment for difficulties that emerge upon return from combat, especially by those who may need it most, suggests an area of military mental healthcare that is in need of attention.

To address this concern, a VR system for PTS treatment could serve as a component within a reconceptualized approach to how the treatment is accessed by service members and veterans returning from combat. Perhaps VR exposure could be embedded within the context of “post-combat reintegration training” whereby the perceived stigma of seeking treatment could be lessened as the service member would be simply involved in this “training” in a similar fashion to other designated duties upon redeployment.

As well, perhaps the use of the term Posttraumatic Stress or Combat Stress Injury may better serve to describe the condition that combat Veterans may experience, in lieu of the more stigmatizing use of the term “disorder”. It will likely take some time to shake the routine use of the term PTSD by both the public and clinical professionals since it has been in play since the 1980s.

But I have recently seen a trend in the current military leadership to use the term PTS without “disorder” attached to the end, so that may suggest a positive shift in perspective that will gradually grow into common use.

b. Will Digital Generation Service Members and Veterans be more Likely to Seek Care with a Virtual Reality Treatment?

VR PTS exposure therapy may also offer an additional attraction and improve treatment-seeking by certain demographic groups in need of care. The current generation of young military personnel, having grown up with digital gaming technology, may actually be more attracted to and comfortable with participation in a VR treatment approach as an alternative to traditional “talk therapy”.

To address this issue, a survey study with 325 Army Service Members from the Fort Lewis/MAMC deployment screening clinic was conducted to assess knowledge of current technologies and attitudes towards the use of technology in behavioral healthcare (Wilson et al., 2008).

One section of the survey asked these active-duty Service Members to rate on a 5-point scale how willing they would be to receive mental health treatment (“Not Willing at All” to “Very Willing”) via traditional approaches (e.g. face-to-face counseling) and a variety of technology-oriented delivery methods (e.g. website, video teleconferencing, use of VR). Eighty-three percent of participants reported that they were neutral-to-very willing to use some form of technology as part of their behavioral healthcare, with 58% reporting some willingness to use a VR treatment program.

Seventy-one percent of Service Members were equally or more willing to use some form of technological treatment than solely talking to a therapist in a traditional setting. Most interesting is that 20% of Service Members who stated they were not willing to seek traditional psychotherapy, rated their willingness to use a VR-based treatment as neutral to very willing.

One possible interpretation of this finding is that a subgroup of this sample of Service Members with a significant disinterest in traditional mental health treatment would be willing to pursue treatment with a VR-based approach. It is also possible that these findings generalize to Service Members who have disengaged from or terminated traditional treatment. As well, informal reports from people who have been treated with this approach suggest that less stigma is experienced with VR, but further research is needed before that observation can be confirmed.

c. The Importance of Clinical Training

One of the guiding principles in our development work concerns how new Virtual Reality systems can extend the skills of a well-trained clinician. Any system of treatment has the potential to do harm if not implemented properly. In this regard, VR Exposure Therapy approaches are not intended to provide automated treatment in a “self-help” format.

The presentation of such emotionally evocative VR combat-related scenarios, while providing treatment options not possible until recently, will most likely produce therapeutic benefits when administered within the context of a thoughtful professional appreciation of the complexity and impact of this disorder. This requires well-trained clinical care providers that understand the unique challenges that they may face with persons suffering from the wounds of war.

To address this issue, 2-day clinical training seminars are regularly conducted, sponsored by the Army and the Air Force, which focuses entirely on the use of the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan system.

This is in addition to the training that must already be documented by the clinician in the conduct of traditional imaginal Exposure Therapy. Such competency certification is essential for the safe application of this treatment approach. Moreover, the University of Southern California’s School of Social Work has stood up a “Masters in Military Social Work” program to specifically train care providers for these unique challenges and have now begun the process for bringing training in VR exposure therapy into their novel curriculum.

11. Future Directions and Potential Controversies

During the course of the ongoing R&D evolution of this application, our design approach has always focused on the creation of a flexible Virtual Reality simulation tool that could address both clinical and scientific PTS research questions in a more comprehensive fashion.

Our vision was not to simply use taxpayer money to build a “one-off” tool for treatment, but instead to build it in a fashion where the simulation could be re-used for other important purposes. In this regard, we are in the process of repurposing the Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan content as tools to investigate a variety of clinical and scientific questions relevant to assessment and training.

Some of these approaches may be controversial and need to be considered from both a clinical and ethical perspective. It is also important that these perspectives and viewpoints should also come from those who “bore the battle” as well as scientists and clinicians who have studied this area. It is only from this type of collaborative interchange between Veterans, Active Duty Service Members, Scientists and Clinicians that thoughtful ideas can be evolved into policy and methods that can make a realistic and positive difference.

As such, I invite those hardy souls who have taken the time to read this detailed report about this project to share your thoughtful feedback on the work and particularly with the new areas we are moving towards that are briefly listed below. These areas include:

a. Assessment at the time of Recruitment –

Would it be possible and ethical to assess service members prior to deployment, in a series of virtual reality combat challenges, to predict potential risk for developing PTS or other mental health difficulties based on their verbal responses and physiological reactions recorded during these virtual engagements? Admittedly, many Service Members play a lot of first-person shooter war games like Call of Duty or Medal of Honor. The key here is to construct simulations, which while created digitally, do not have the features of a game, such as multiple lives, unlimited firepower, etc.

For assessment purposes, events that have been reported by Combat Veterans as emotionally troubling could be scripted out in the virtual world, with the goal being the measurement of recruits’ reactions that might predict a pre-PTS emotional response.

In my way of thinking, if someone shows an extreme physiological emotional reaction to this sort of stimuli in a simulation, perhaps they may not be cut out for combat? This would require a change from current military thinking, where doctrine dictates that anyone can be made into an infantryman.

Those who may display such reactions and would be predicted to be most at risk to have a challenging stress reaction post-combat, could either be assigned non-combat duties or not accepted into the services. People are not accepted into the military for a lot of reasons that are more easily measurable, such as physical fitness or a significant chronic health condition.

In this case, the challenge would be inaccurately measuring emotional reactivity and coping ability and that would need to be established in the first place with research using this approach with all Service Members, measuring and recording physiological reactions to establish a baseline and also determine if consistent patterns of response do in fact exist.

Then these service members would be closely monitored for their mental health status over their term of duty. Once a large enough group of Service Members and Vets were then identified as having significant problems following their combat deployments, it would be possible to go back and analyze their physiological data from the earlier simulation experience and look for a consistent reactivity pattern in this group that could serve as a marker for predicting problems in future recruits.

The downside for this type of research is significant. These would include the fact that the military does not want to lose volunteer recruits, this type of research is long-term and costly, and there is a chance that in the end, future service members could be misidentified as high risk and be denied access to being in the military. But is the current alternative any better?

b. Stress Resilience Training Prior to Deployment – The next twist for the use of Virtual Reality Combat Simulations follows from the last issue: Can we train emotional coping skills in those that are identified as high risk for post-combat emotional problems, and then better train and prepare them for the “savage clash of wills” (TRADOC Pam 525-3-7-01, pp. 15) that is the job of combat? Recently, the military has focused a lot of attention on the concept of “Stress Resilience Training”.

Specifically, Army Brigadier General Rhonda Cornum directs the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program which has put a lot of resources into the creation and dissemination of training to improve emotional coping skills and ultimate resilience in ALL Army service members. This approach draws a lot of input from principles of Cognitive Behavioral science, that in a nutshell, advances the view that it is not the event that causes the emotion, but rather it is how you appraise the event (based on your internal thinking about the event) that leads to the emotion.

If you buy this view, then it follows that “internal thinking” about combat events can be “taught” in a way that leads to more healthy and resilient reactions to stress. This approach does not imply that people with good learned coping skills do not feel emotional pain or that they should be turned into emotionally numb automatons.

Instead, the aim is to teach skills that may assist soldiers in an effort to cope with traumatic stressors more successfully and achieve Post Adversity Growth (Cornum, 2009) from their experiences in combat.

Other branches have also begun looking at similar methods and some elements are part of online programs like Battlemind.

We are exploring the reuse of Virtual Iraq/Afghanistan scenes as tools for providing simulations (again, informed by Combat Veterans) that are akin to “emotional obstacle courses” where such coping skills could theoretically be trained within a relevant simulated context under very controlled conditions. Service members could engage in a variety of virtual “missions” where emotionally challenging situations are created that may provide a more meaningful context in which to learn and practice cognitive coping strategies that better psychologically prepare humans for what might occur in real combat situations. In this fashion, the simulation would become a tool for the more realistic/relevant training of emotional coping strategies.