By Khalil Nouri STAFF WRITER

VETERANS TODAY

Major Jim Gant, an Army silver star Green Beret hero, considered the best field grade officer for the “AfPak Hands” program. He is also the author of “One Tribe at a Time” and an outspoken advocate of Afghan tribal engagement strategy (TES), who lived and breathed the notion for years, and outstandingly, he has the ears and attention of the brass in his chain of command.

Gant’s proposal centers on the idea that, “it’s insignificant as how many troops are deployed; it’s how they can be best utilized.” He is promoting; the field American “tribal engagement teams” (TET) to live with — and fight alongside — Pashtun tribesmen, who dominate Southern and Eastern Afghanistan with little faith in, or loyalty to, the central government. His advocacy is to use the centuries-old tribal code of honor, justice and revenge, called “Pashtunwali” system (the only system of governance) to defeat the Taliban.

But the question remains: would the tribal strategy that perceived magically to charm Afghanistan’s future be achievable?

Major Gant’s outstanding and enthusiastic presentation not only reflects the correct itinerary but also in close vicinity of integrating the real aspects of centuries old Afghan tribal structure into a practical model that could eventually change the entire dynamics of the war in Afghanistan.

Moreover, if this is a chance for succeeding and bringing peace and stability to Afghanistan, it will mean; learning from our mistakes and more importantly, recognizing the obstacle in terms of culture, norms, geopolitics, and religion, thus, not to deny them and not to ignore them.

Mission Hurdles

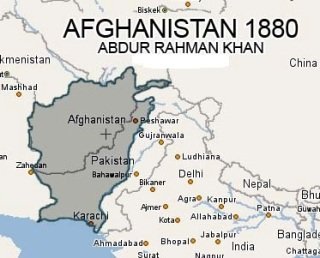

Taming “Yaghistan” (the land of the unruly) — as the Afghans traditionally labeled Afghanistan — is the most burdensome and complex mission since WWII; first and foremost, nothing fundamentally will change in the region until the issue with the Durand line is resolved. The creation of the border line since inception, its failure then — to regularize the position, and its continued failure, should be a justifiable reason for a thorough UN evaluation and revision.

As a clear reminder that, ever since the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan in 1947, Afghanistan and Pakistan have been adversaries, with the tribal areas and the Northwest frontier territories being at the center of the dispute.

As Emir Abdul Rahman, ruler of Afghanistan when the Durand mission did its work in (1893) writes to the Viceroy of India, warning him of the dangers of splitting the peoples of the tribal areas. “If you should cut them out of my dominions,” he said, “they will neither be of any use to you nor to me: you will always be engaged in fighting and troubles with them, and they will always go on plundering.”

Within seven years, the Emir was to be proven right, with the British having to put down major uprisings, dealing with — North West Frontier Agencies (NWFA) and Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) — Chitral, Bajaur, Malakand, Waziri and Afridi wars, and now, history is repeating itself except with vast span of the Pashtun belt gearing for a state of chaos.

The Irony is that, with the current coalition policy of expanding the Afghan Army, the Emir was arguing back in 1893 that the “brave warriors” of the tribal regions would “make a very strong force” and that only a ruler of Afghanistan could “make them peaceful subjects”. Divorced from Afghanistan, they are the problem— within Afghanistan, they could be part of the solution. Hence, broadening Major Gant’s policy to the Pakistan’s neglected areas of FATA and NWFP without resolving the Durand line will be hopeless.

Aside from the above obscurity, many Afghans and Afghan-Americans believe that no matter how well-trained or Afghan-culture sensitive U.S. Special Forces are, they will never know enough about a specific local area and its indigenous norms to carry out their daily counterinsurgency campaign effectively; because the people will never trust them enough to share everything. Perhaps one bonanza by TET was effectively struck with the Mangal tribal elder Malik Noor Afzhal — as Major Gant calls him “Sitting Bull” — and apparently no other tribal elders were put to attest for the workability of such doctrine.

In fact, this is also Major Gant’s main challenge as he states in his paper; “The situation at each tribe will be complex and will vary with each tribe.”

True, tribal structures are not uniform across Afghanistan, they are very complex, and there is no standardized or “one size fits all” setting. Unlike the Paktia tribes— the traditional political authorities are in fact village and or tribal elders and or local Mullahs or Maulavis; who do not share power equally and do not exist in a “traditional” sense of the word, and very much will not invigorate the social and moral fabric of the society— However, the Durrani and Ghilzai tribes in Southern Afghanistan have no tradition of raising volunteer forces (Arbaki in Pashto language) to maintain local Security. This is why Taliban managed to emerge and successfully (but deceitfully) sell themselves as neighborhood Gladiator figures, protecting regular folks from marauding warlords.

But the tribal leaders among the tribes still command considerable respect and exert influence in their communities. The fact is that, tribal leaders with deep roots in local communities can make a difference, and therefore, the tribal mindset differs tribe to tribe throughout Afghanistan.

The costs

In fact, as a roadmap to success for Afghanistan, TES will require a complete paradigm shift in Pentagon’s operational culture— from conventional risk-averse micromanagement to unconventional decision making, Command and Control and Rules of Engagement. This is a significant cost in addition to financially prospering the tribes.

The risks

For this — One Tribe at a Time — model to bear fruit; the deploying courageous volunteers TET must be “sincere and devoted volunteers” for popular resistances against oppressive forces. Whenever such agile and courageously committed fighters are introduced to live in local tribal communities and even when they are personally driven to help the society fight against local oppressors. They still could be viewed in the eyes of indigenous that they are actually working for a larger, but hidden, oppressive Empire,— United States — as was the case with the “best and brightest” in Vietnam, then the results can be disastrous— because the real motive is viewed as fabrication, a sham, and at heart, a lie.

The gravest concern is, the U.S. may eventually again abandon Afghanistan — as foreign powers come and go — and the tribes to whom coalition forces have promised long-term support will be left to be massacred by a vengefulTalibn.

If Obama’s recent call to start bringing the troops home in 18 months, and also with fragile NATO alliance that the Dutch to depart first and then the Canadians, will likely to create an alliance of worrisome tribal chieftains whether to continue trusting the U.S. and NATO further. This could tip the balance into a state of confusion and may cause reluctance to prop up tranquility in Afghanistan.

Despite the fact that the code of (Pashtunwali) amongst some tribes is considered primary than the religion of Islam, but still If TET does not have the same devotion towards Islam as the inhabitants do, then they are considered outsiders. The mosque remains the clandestine decision place for a quick close-door Jirgah (Grand Assembly) where one cannot even infiltrate as what was discussed amongst the tribal members. At the end of the day, the final decision will network itself in agility to other mosques where public awareness could multiply exponentially.

Gant’s notion requires a profound understanding of Afghan tribal politics; for one to walk a fine-line between tribal community feuds he must be capable of extinguishing a potential rebellion that could easily be ignited by a meaningless or sensitive tribal issue. For example; using one tribe against another or taking sides with one or interference into tribal affairs could result in an inflammable consequence.

As Lord Roberts British viceroy to Kandahar recognized this when, at the end of the second Afghan war in 1880 he said, “the less they –Afghans—are able to see us, the less likely are to hate us…..we will have much greater chance of getting the Afghans on our side if we abstain from any interference in their internal affairs whatsoever.”

However, it is needles to say that the Afghan society is a barely penetrable jungle— with its more than fifty ethnic groups, 400 plus tribes and vast sub tribes and clans, religious groups, mystical brotherhoods, mafia networks, village communities and nomads’ camps, with the clienteles of political actors, the militias of the warlords, bands of robbers and urban neighborhoods, plus marriage alliances, professional guilds and internationally networked trade and bazaar structures. In such a jungle, even the gutsiest gladiator with all his might is quickly lost.

Alternate Solution

Day by day a growing chorus of voices is heard saying that the tribes are the solution in Afghanistan. This very powerful grassroots movement is blossoming; and it can give the Afghan people new hope, self-esteem and a sense of belonging. But, to make sure that there is success to this notion, an effective bottom-up approach tool is required to match the existing top-down approach so that jointly both approaches can rescue the nation.

One must bear in mind that, the importance of understanding the strength and degree of tribe and clan-based loyalties and what happens when foreign occupiers interfere in the traditional order of balance and stability that took thousands of years to set in place; foreign displacement of Pashtun authority will always result in resentment exponentially within layers of tribal hierarchy.

After decades of wars, famine and all around instability; dire sociological stresses, severe ethnic tensions, imbalance of societal structure, and downward native vibrancy (depression) has resulted; but, all could be overturned if a robust and well intended bottom-up approach can be introduced.

But, to overcome chronic national symptoms and restore the nation’s cultural, social, political and economic health; a practical blueprint should be defined as a framework in terms of “accessible resources.” The very necessary and indispensable resources that Afghanistan desperately needs today are Expatriate Afghans as well as the underutilized Afghans inside Afghanistan.

The current U.S. military operation in Afghanistan is just beginning to realize the importance of the tribes. That is why; the Community Defense Initiative (CDI) is now being enthusiastically backed by General Stanley McChrystal. This is a huge transition for the U.S. and NATO operations that can be valued more deeply by engaging a framework for an Afghan-American to tribal Afghan cause.

Unlike Iraq, the degree of tribal complexity in Afghanistan is much higher. We believe, enlisting tribes against militants not only carries risks in terms of promoting warlord strategy, but also could undermine the hard work which was done previously disarming proscribed militias. Therefore, in contrary to Major Jim Gant’s doctrine, our approach is – a clear Afghan solution to an Afghan cause – considered a nonmilitary one.

According to the Census Bureau, there are between 200,000 plus Expatriate Afghan-Americans. Their ethnic backgrounds reflect ethnicities of all Afghan origins, and most have preserved their close ties with their tribes and clans inside Afghanistan. Culturally, their family bond and social intimacy is as strong as ever. Furthermore, the strength and degree of tribe and clan-based loyalties is the solid foundation that has knitted the tribal constituents for centuries.

Placing the above circumstances into perspective; the question arises as to how a thriving bottom-up approach can be implemented?

The real method

Initially the formula can be an empowerment of face to face interaction between; an Afghan in the U.S. (a tribal representative) and an Afghan in Afghanistan (a tribal leader), whose tribal roots are connected and are in acquaintanceship to each other. In regards to a tribal representative, he is not only loyal to his tribe but also to his adopted counrty the United States. Therefore, a genuine connection with “strings-attached” can be achieved. On the contrary, in the perception of top-down approach, trustworthiness and tribal interlink is unachievable, and evidently has resulted in failure and disappointment.

Furthermore, the tribal leader and tribal representative will be implementing the said mutual interaction exclusively in a business tribal council framework we call “business-Jirgah to business-Jirgah” –- or “Biz Jirgah to Biz Jirgah”— which should be applicable within local responsibilities and local structure, with cost effectiveness in mind, and free of foreign bureaucracies.

In addition, “Biz Jirgah to Biz Jirgah” involves establishing business relationships, and actual business initiatives on a people to people (rather than a nation to nation) basis, where each Afghan tribe is invited and encouraged to establish a business that can work closely with its Afghan-American business counterpoint and eventually grow from micro to macro.

These standardized and fixed priced businesses — specialized assets — can reflect basic human necessities such as potable water, cold storages, fish farms, chicken farms, and so forth; while they can be built in areas that are in compliance with individual tribal approval.

In addition, by using this concept which is in phase with thousands of years of customary Afghan culture, the stigma of foreign intervention is diminished and real dialogue and trust can be developed. As the result, the seeds of trust between Afghan and American business interests are firmly planted, and needed infrastructure projects can be completed within acceptable time-frames and maintained for generations.

This indigenous interaction can not only strike a successful agreement between the tribal players, but it can also be cost effective in terms of non obligation of force protection, since no American Military Civil Affairs or International Development personnel are engaged.

Major Gant’s “One Tribe at a Time” initiative—minus to live with and fight alongside the tribes—can easily be persevered and switched for a genuine and convincing dialogue within the Afghan tribal communities in the United States, Europe and Elsewhere in the world. It is a doable prospect but has to be an Afghan instigation only.

Once the communities inside Afghanistan start ascending towards prosperity, self fortification against intruders and area insurgency will be weakened, and at the end of day, flourishing and self esteemed communities likely to join together and thrive economically with domino effects.

In the initial stages, this program requires full U.S. financial support, so that the average person’s day-to-day necessities come from income he generates; and he can turn away from insurgency recruitment for hire to feed his family.

And finally, no central agency in Kabul can ever know the priority needs of people in every Afghan village, and unity cannot be delivered from the top. But when local leaders, engaged — for an Afghan solution — in the nitty-gritty of local policymaking, practice fairness and inclusion, the people will follow. A weak state cannot be made strong overnight. But it can set up the systems that catalyze strong local communities by adopting village by village “Biz Jirgah to Biz Jirgah” initiatives.

In hindsight, Major Jim Gant does not need to take the risk fighting alongside the tribes to protect them against the militants. With this flourishing economical opportunity, they will do anything to protect themselves and their communities against any obstacle.

Khalil Nouri is the cofounder of New World Strategies Coalition Inc., a native think tank for nonmilitary solution studies for Afghanistan. www.nwscinc.org

Khalil Nouri was born in an Afghan political family. His father, uncles, and cousins were all career diplomats in the Afghan government. His father was also amongst the very first in 1944 to open and work in the Afghan Embassy in Washington D.C., and subsequently his diplomatic career was in Moscow, Pakistan, London and Indonesia. Throughout all this time, since 1960’s, Khalil grew to be exposed in Afghan politics and foreign policy. During the past 35 years he has been closely following the dreadful situation in Afghanistan. His years of self- contemplation of complex Afghan political strife and also his recognized tribal roots gave him the upper edge to understand the exact symptoms of the grim situation in Afghanistan. In that regards, he sees himself being part of the solution for a stable and a prosperous Afghanistan, similar to the one he once knew. One of his major duties at the beginning of Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan in 2002 was advisory role to LTG Franklin Hegenbeck. He has worked closely with the Afghan tribes and his tribal exposure is well tailored for unobstructed cross-cultural boundaries within all Afghan ethnicities. He takes pride in his family lineage specifically with the last name “Nouri” surnamed from his great-grandfather “Nour Mohammad Khan” uncle to King Nader-Shah and governor of Kandahar in 1830, who signed the British defeat and exit conformity leaving the last Afghan territory in second Anglo-Afghan war. Khalil is a guest columnist for Seattle Times, McClatchy News Tribune, Laguna Journal, Canada Free Press, Salem News, Opinion Maker and a staff writer for Veterans Today. He is the cofounder of NWSC Inc. (New World Strategies Coalition Inc.) a center for Integrative-Studies and a center for Integrative-Action that consists of 24- nonmilitary solution for Afghanistan. The function of the Integrative-Studies division (a native Afghan think tank) is to create ideas and then evolve them into concepts that can be turned over to the Integrative-Action division for implementation. Khalil has been a Boeing Engineer in Commercial Airplane Group since 1990, he moved to the United States in 1974. He has a Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering, and currently enrolled in Masters of Science program in Diplomacy / Foreign Policy.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy