“Water and air, the two essential fluids on which all life depends, have become global garbage cans.”

Jacques Cousteau (1910-1997)

Updated 12/29/2010

(IRVINE, CA) – I don’t believe in ghosts. If I ran into one or two, maybe I’d change my mind. The stories of lights in the former Marine Corps Air Stations El Toro’s control tower when the power was cut off in July 1999 may be just someone’s wild imagination or I guess if you believe in paranormal activity, maybe the ghosts of Marines who served on the base and returned to haunt the place. No question there’s good reasons for haunting the former base.

At night, the former base takes on the appearance of a ghost town. With the power to buildings cut off and hundreds of dilapidated buildings still standing, moonlight can play tricks on your mind. Shadows move or seem to move and it doesn’t take too long before normally rational people see things that are not there.

At night, the former base takes on the appearance of a ghost town. With the power to buildings cut off and hundreds of dilapidated buildings still standing, moonlight can play tricks on your mind. Shadows move or seem to move and it doesn’t take too long before normally rational people see things that are not there.

Some things that you can’t see can kill you and the contaminants in the Shallow Groundwater Unit or SGU (Navy’s terminology) at El Toro were deadly, even if you couldn’t see them.

The Navy’s investigation identified 25 contaminated sites on the base, 11 of them were in the most industrialized Southwest quadrant where the base wells and Marine transport aircraft were serviced in two huge maintenance hangars.[1]

As it turned out, the Navy wells were in this area, too. The TCE plume cut a path right through the Navy wells, all except one constructed in WW II, one well formerly an agricultural well owed by the Irvine Company, all of the original well construction drawings missing with their critical well screen intervals, one well screen interval found in the contaminated SGU from a physical inspection prior to sealing, all remaining wells sealed with concrete without a physical inspection to locate their well screens, one well found contaminated with TCE at 12 ug/L in 1995 and other with petroleum hydrocarbons in 2005, primarily with motor oil at 1,200,000 milligram per kilogram (mg/kg). The Navy’s pumping records (penciled on eight column worksheets by El Toro Public Works Department) arbitrarily cut off months before an early municipal water service contract for softened water from the Metropolitan Water District, the quantity of water from MWD insufficient to meet the demands for water for both El Toro and the Santa Ana Air Facility (only ½ of the maximum output from El Toro’s 4 productive wells), and the official government contract file missing for a follow-on contract with the Irvine Ranch Water District that continued to supply water to the base at least until the public auction sale in July 2005.

EPA reported that “the primary source of VOCs is beneath Buildings [Hangars] 296 and 297.” [2]

EPA’s 1997 Record of Decision for Site 24 noted that, “the trend of increasing soil gas concentrations with depth suggests a depleting source at the surface that is consistent with the assumed end of TCE usage in approximately 1975.” This comment grabbed my attention. The cut off date of 1975 was based on interviews with current and former employees.

The experts were wrong. Both Tim King and I have received multiple reports from Marine veterans of use of TCE at El Toro until the 1990s. In fact, one RAB (Restoration Advisory Board) member reported to the Navy that TCE drums were buried on the base to keep them from being observed during inspections by the Marine Corps Inspector General.

John Uldrich, another former El Toro Marine, had seen my blog site on El Toro and contacted me in 2007.

Uldrich was assigned to MWSG-37 in 1957-1958: “We were on the upper deck of the big hangar that, as I recall, was the ‘eastern hangar’ [Bldg. 296] of the two big ones. Saw a lot of TCE ‘up-close-and-personal’ as the aircraft strip down was done below us. At the TCE ‘hose-down’ stage, clouds of the stuff would waft on the wind – get into the upper level. As I recall, a single F9F could use up to a 1/3rd of a 55-gallon drum. Excess TCE simply drained into a sump outside the hangar door. If you were entering or exiting the hangar while this segment was underway you had to stand back and not let the stuff get on your uniform of the day. If you got spritized – goodbye your clothing – would eat away the cloth like a moth. Replacement, as I recall, was at your own expense.”[3]

Another El Toro Marine described a kind of “dry cleaning” operation for aircraft parts using TCE as the cleaning solvent in Hangar 296.

Retired Marine Sergeant Major Bill Sears told me, “When I was a member of VMR 352 or 152 in the early ’50’s I worked in the engine shop in Hanger 296. One of my duties was to degrease engine parts. That was done in the large tank or vat into which I periodically hoisted 55 gallon drums, using the overhead crane, and emptied the contents of TCE/PCE into the water in the tank. By heating the mixture a vapor was released into which I lowered a large metal basket containing parts to be cleaned and in seconds it was done. I have no idea how the waste was disposed of. I believe the tank was located in the attached Bldg. on the east Side of [Bldg 296] as it is shown. I and my family spent 1967-1969 in the Lejeune area, first as Sgt Maj of 1/6 then as Sgt Maj of MACS 5 at New River. You could probably find many other Marines and their families that would be considered as getting a double whammy.”

Uldrich has been tracking what he believed to be a “cancer cluster” at El Toro for several years. According to Uldrich, “The problem is that a lot of these Marines are either dead or dying (family members included). You can see this by reading through the Marine Air Transport Association quarterly newspapers going back to 2000. The ‘obits’ would leave one to believe that dozens of these Marines – spanning literally decades of service – have died from conditions that fairly scream out “CLUSTER CANCER” with TCE fingerprints!”

My Google blog site was attracting attention. El Toro veterans and dependents were emailing me about their experiences, asking questions about the water. The contamination of the Camp Lejeune base wells was national news and many El Toro veterans had questions about El Toro’s wells.

Base Wells and Municipal Water Purchases

I had little information about the source of water on the base. Nothing on the details of the ‘TCE plume.’ I learned fairly quickly that there’s nothing pretty about a TCE plume. You can’t see it as it moves through the aquifer. My research showed that as TCE and other pollutants are released to the ground, they work their way down into the groundwater. If enough TCE gets into the groundwater, it forms a column of polluted water moving in the aquifer called a TCE plume.

From a call to Naval Facility Engineering Command in San Diego, I learned that the Navy had negotiated a municipal water services contract with the Metropolitan Water District in 1951, followed by another contract with the Irvine Ranch Water District in the 1960s. My NAVFAC contact didn’t have a copy of the contracts. He suggested I contact the water districts.

This looked like a waste of time. It looked like the base wells were abandoned 60 years ago.

El Toro had used well water at one time, but then awarded municipal water service contracts very early. Maybe the base wells were abandoned when municipal water was purchased. But, things don’t always turn out as simple as they look. The MWD contract was too far back (60 years) to even attempt to get any useful information from the water district or the Navy. The official MWD government contract was destroyed years ago and I doubted if MWD would have any records, or if they were available, be willing to share them with me.

But the IRWD contract file might just be available, especially since the Navy didn’t sell the base until 2005 and IRWD had to continue to supply water under the Navy contract until the base was sold.

In October 2007, Jan Whitacre of the Navy BRAC West in San Diego made it very clear in a telephone call regarding two Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests that the voluminous Navy records on El Toro would fill several box cars and I couldn’t afford the costs of copying and shipment. I got the message. The game was hardball and the Navy wasn’t going to roll-over and give some Marine veteran free access to Navy records. I had asked for a base map and building directory for El Toro for the years 1963 and 1964 and copies of all files, correspondence or other records concerning exposure to VOC contaminants and any contamination in close proximity to my living quarters and working areas at El Toro. I agreed to limit my FOIA request to one electronic copy of a 1954 map and building directory and several CDs containing the Environmental Baseline Survey (EBS), the Finding of Suitability to Transfer (FOST). The map was forwarded to me via email.

I emailed the pdf copy of the 1954 map and building directory to Uldrich in Minnesota. The file could be enlarged. A quick review of the map and directory showed base wells and pump houses in the Southwest quadrant of the airfield. Not a great deal of detail but the wells were listed on the directory.

One thing that Marines are noted for is their persistence. Call it what you want. Resolute, determined, steadfast, committed, dedicated, devoted, diligent. Uldrich and I were not going to quit until we got some answers. Both of us had survived cancer and in my case the VA had agreed that TCE at El Toro was as least as likely as not the cause. If not for ourselves, we owed it to the Marines we served with.

Uldrich remembered reading news stories in the Flight Jacket (base newspaper) about the base wells from his tour at El Toro in the late 50s.

Just because there were wells on the base that happened to be located in the Southwest quadrant that didn’t mean that the well water was contaminated. Did the TCE plume contaminate the base wells?

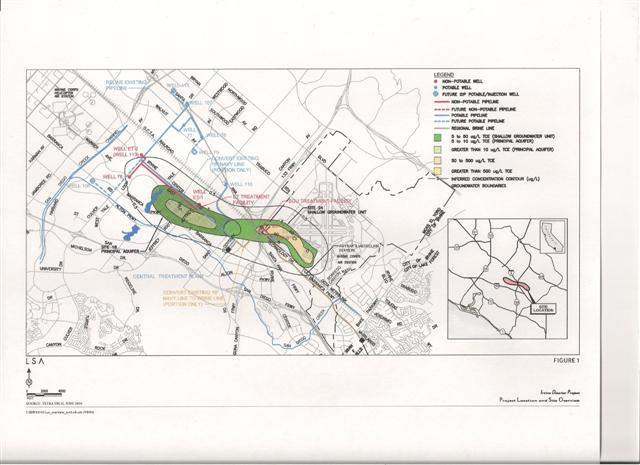

Based on a Google search, I found a 2002 Geoscience Support Services report, which included graphs of the TCE plume in the SGU at El Toro (Figure 21).

The TCE plume cut a path right through the base wells. The Navy wells couldn’t have been placed in a worst area. They were all in the “red area” in Figure 21 where TCE averaged from 50 ug/L (or 50 parts per billion) to greater than 500 ug/L or from 10 to 100 times EPA’s Maximum Contaminant Level for TCE of 5 ug/L.

Both the Navy and EPA confirmed that there was no need to be concerned. The government’s position was that El Toro’s wells went deep into the uncontaminated Principal Aquifer (PA) under the base, a clay barrier separated the contaminated SGU from the PA, the base had purchased municipal water as early as 1951 and the well pumping records stopped as of December 1950. No dates were known when the wells were abandoned but the pumping records stopped with the MWD municipal water purchase and, in any case, the wells drew water from the uncontained PA.

I had been an auditor with EPA’s Inspector General in the 1970s and knew from experience that things are sometimes not as clear cut as they seemed. One thing that bothered me was the cost of water.

Why would the Navy purchase scarce and expensive municipal water in Southern California when they could get all the free water needed from the base wells?

I didn’t doubt that TCE and other contaminants could have made their way into the SGU by 1950, but the Navy didn’t have the capability to test for organic solvents like TCE for at least another decade, maybe later.

It didn’t make sense for the Navy to abandon water wells that were less than 10 years old without good reason. And, if it wasn’t TCE that forced the Navy to purchase municipal water, what was it?

The government contract with MWD had the technical justification to support the contract award but that file was not a permanent record, no longer available, probably destroyed in accordance with Federal record retention requirement in the mid-1970s.

I would have to use Freedom of Information (FOIAs) to obtain information from the Navy. FOIAs would take time to process. In the meantime, a search of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) might produce some valuable records.

The search leads me to NARA’s Pacific Region in Laguna Niguel, CA. Contact with their archivist and a records search by his staff confirmed that they had copies of El Toro’s water distribution engineering drawings.

NARA was very supportive. Could I stop by and review the records before they made pdf copies for me? I had to decline their offer. New Jersey was just too far and trip to Laguna Niguel to look at some engineering drawings was not in my budget. Could NARA make pdf copies and mail them to me? Their answer was, “Yes.”

One of the NARA engineering drawing was a copy of El Toro’s Public Works drawing PU-1233, dated April 1954. This drawing showed El Toro’s water distribution system included Navy Wells #1, #2, #4, #5, #6, Irvine Company Well #55 and a 14 inch main from the Metropolitan Water District (MWD).

Irvine Co. Well #55 was connected to a 12 inch Irvine Co. main; while the five Navy wells were connected to mains servicing the base (Navy Well #3 was marked as a “Dry Hole.) None of the Navy wells were marked as abandoned.

This engineering drawing supported the use of the base wells several years after the award of a municipal water services contract in 1951. Maybe Uldrich was right after all. El Toro’s base wells were in production in the 1950s, too. This still didn’t mean they were contaminated, even if the TCE plume cut a path right through them. The risk of contamination from their location was a possibility. However, the Navy’s insistence that the wells drew water from the uncontaminated PA seemed to discount any contamination.

TCE in Wells

According to an Orange County Register news story of August 29, 1987, “State Water Officials Threaten to Sue Marines over Contaminated Wells,” Orange County Water District personnel during a routine agricultural well inspection in 1985 found two agricultural wells on Irvine Company land and one on the base contaminated with TCE. The two Irvine Company wells were located 7,000 and 2,000 feet west of the base. TCE at 48 ppb (parts per billion) was found in the well that was 7,000 feet west of the base. This was nearly 10 times the EPA Maximum Contaminate Level (MCL) of 5 ppb. The TCE contamination in the base well was below the EPA MCL. The only agriculture well on the base in 1985 was Irvine Company Well #55, just northwest of Runway 7L and out of the TCE footprint.

Since the off base wells were down gradient from El Toro and TCE was a known degreaser for aircraft parts on the base for decades, El Toro was the likely source for the contamination.

In July 1987, the Santa Ana Regional Water Quality Control Board ordered the Marine Corps to investigate the source of the contamination and clean-up the wells.

The reaction of the Marine Corps was to vehemently deny any responsibility for TCE contamination of off-base wells.

Captain S. R. Holm replied to the order, “There does not seem to be any substantiation for the conclusion that the contamination does in fact come this air station.” Huh?

In 1987, El Toro was surrounded by agricultural fields and Orange groves.

Demonstrating an incredible amount of hubris, Captain Holm told the Santa Ana Regional Water Quality Control Board that the Marine Corps would clean up the well on base property but the Irvine Company should bear the costs of “constructing wells to monitor the contamination [off-base] since virtually all of it is underneath the company’s land.”

TCE is an industrial solvent, not used in agriculture. TCE had been used at El Toro for decades, much of it in the most industrialized portion of the base where the aquifers under the base flow in the direction of the contaminated wells.

According to the same Orange County Register news story of August 29th, the explanation for resistance by the Marines came from James Reilly, Director of Water Quality for the Orange County Water District, “They don’t want to do anything until they study the thing to death. This isn’t the first time that the water board has struggled with the Marines.”

Navy Agrees El Toro is the Source of the TCE Plume

Six years after TCE was discovered in three agricultural wells, the Navy finally agreed that El Toro was the source of the TCE plume.

After extensive investigation by the Navy and EPA, the Justice Department in September 2001 finalized a settlement that involved former MCAS El Toro, recognizing the base had released volatile organic compounds into shallow groundwater below the surface of the base and ultimately into an adjacent deeper off-base aquifer.

According to a Justice Department report, “the deeper aquifer was also contaminated by nitrates and total dissolved solids from the activities of other entities, and the Water Districts for Orange County and the Irvine Ranch had undertaken a long-term project to pump and treat the water from the deeper aquifer. Through the settlement agreement, the two Water Districts will now be responsible for the long-term cleanup of both the off-base deeper aquifer and the on-base shallow groundwater, at a projected cost of $97 million. In return, the United States will contribute $27.25 million toward the cost of the cleanup. This arrangement results in a significant cost savings both to the United States and to the Water Districts due to the cost efficiency of constructing and operating a total treatment system for both of the contaminated areas.”

What about the Navy wells at El Toro? Was there evidence of contamination in the base wells?

Destruction of Navy Wells and Missing Records

The well screens are the first point that water and any contaminants enter a well. EPA Region 3 reported that, “a perforated screen installed on a section of the well casing will allow water to enter the well hole only along the length of the well screen at the depth that the well screen is installed.”

The original well construction drawings for El Toro’s Navy wells show the locations of the well screen intervals. However, the Navy reported that all of the original well construction drawings were missing. Without a physical inspection of each well, there was no way to know the location of the well screen intervals.

EPA Region 9 in a reply to my “EPA hot line” noted that the Orange County Health Care Agency (OCHCA) in Santa Ana was responsible for issuing well destruction permits and

A few telephone calls and emails to OCHCA and I had a stack of well destruction reports filed by the Navy on El Toro’s base wells.

All of the Navy wells were sealed under OCHCA permits with two exceptions. Navy Well #3 was a dry hole and never in production. No problem there. However, Navy Well #5 was a good producer but was destroyed without a OCHCA permit, probably sometime in 1997.

The remaining Navy wells were sealed from 1998 until 2007. For these wells the Navy obtained well destruction permits from the OCHCA. Well destruction reports were filed with this agency.

The first well destroyed under OCHCA permit was Navy Well #4 on April 1, 1998. The permit was obtained by the Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Southwest Division. The Navy directed OHM Remediation Services Corporation (OHM), the Navy’s consulting engineer, to “video log well to total depth and determine wells screen location and condition of well casing.” [4]

The OHM Well Destruction Report on AW #4, dated April 9, 1998, reported that, “a video logging of the well showed evidence of extreme fouling, and the well casing was heavily encrusted…the location of the top of the screen could not be determined [my emphasis].” On March 10th, OHM measured the bottom of the well at 494 feet bgs. The well casing was scrubbed with a wire brush as directed. OHM noted that on March 13th, the wire brush could not go past 452 feet bgs. The impediment at 452 feet bgs “suggested a failure in the well casing at 452 feet bgs, which allowed the formation material into the well.”

OHM reported that the well screen was a series of vertical slots, hand cut by torch and the video showed that the top of the screen started “at approximately” 210 feet bgs and continued all the way to the bottom. According to the Navy, the SGU under Site 24 went to 250 feet bgs.

At least 40 feet and more likely than not more of the well screen interval was in the contaminated SGU. The very first well inspected for the well screen interval found the screen open in the contaminated SGU. To make matters worse, a water sample from this well in 1995 found 12 ug/L of TCE. Definitely not good news.

Was Navy Well #4’s well screen interval an anomaly? Did the driller make a critical error in constructing the well? Without the original well construction drawings, the only way to know for sure was to physically inspect each well before sealing them. The obvious risk was that if all of the other Navy wells constructed with some portion of their well screen intervals in the contaminated SGU, then the well water was contaminated with VOCs and other contaminants.

The Navy didn’t take the “high road.” The Navy didn’t ask their consulting engineers to locate any more well screen intervals. All of the remaining wells were sealed in concrete without knowing the locations of the well screen intervals. No inspection is possible now; they’re all wearing concrete shoes.

In 2007, Navy Well #2 was sealed but not before a water sample found 1,200,000 milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg) of petroleum hydrocarbons in the well. The source of this contamination may have been a nearby underground fuel storage tank.

Navy’s Pumping Records Incomplete

The Navy’s Fact Sheet of August 2008 noted that “monthly pumping records available from May 1943 to December 1950 indicate the maximum combined flow from these six [Navy] wells was 900 gallons per minute in August 1945.”

The earliest water distribution drawing for El Toro is from November 1942. We obtained a copy from NARA’s Pacific Region of the November 1942 “Water Supply Key Plan.”. This drawing shows the water distribution system for El Toro consisted of Navy Well #2, Irvine Company Wells #55, #57 and #61. Irvine Company Well #57 would become Navy Well #1.[5]

During WW II, the Navy constructed Navy Wells #3 (Dry Hole), #4, #5, and #6. As part of a settlement in District court in October 1949, the government gave the Irvine Company a perpetual easement for the operation, maintenance, repair, replacement and use of Well #55, its pumping plant, pipe line for production and transportation of water for their agricultural fields surrounding the base.

All of the Navy wells were in the footprint of the TCE plume spreading into Orange County. Both Irvine Company Wells #55 and 61 were outside of the path of the TCE plume.

The Navy’s position is that the lack of pumping records after December 1950 and the purchase of municipal water in 1951 were evidence that the base wells were abandoned early.

Based on our review, the best that can be said about the Navy’s pumping records are that they are incomplete. The maximum combined flow from four Navy wells (not six as reported) was 900 gallons per minute in August 1949 (not 1945 as reported). Navy Well No. 3 was a dry hole while Navy Well #4 was in production for only five months during WWII. So only four Navy wells were in production at any one time, not six as reported by the Navy.

The connection to MWD was not made until June 1951.[6] The base wells had to supply water during this six month period. Again, the pumping records do not show the quantify of water pumped during this period.

There are good reasons to believe that El Toro continues to pump water from the base wells after the MWD contract delivery in June 1951:

- Water supplied by MWD was only half of the maximum output of the 4 Navy base wells (450 gallons per minute vs. 900 gallons per minute);

- The base wells were part of the El Toro’s water distribution system in the 1954 as shown on an El Toro water distribution drawing;

- In 1951 the base wells were less than 10 years old with years of useful life and no logical reason to abandon them; and

- The purchase of softened water from MWD may have been justified by the need to reduce the hardness of water from the base well by blending their output with softened municipal water. TCE contamination was not a factor in 1951 since there was no test for TCE in well water at that early date and no requirement for El Toro to monitor organic solvents like TCE in well water.

How do you explain the absence of pumping records after December 1950? This is now over 60 years. Were they lost? Trashed? We don’t know. The facts are that the MWD delivery of softened water to both El Toro and Santa Ana didn’t take place until June 4, 1951 and the base’s pumping records stop in December 1950.

What about El Toro’s water distribution records? The Navy confirmed that the water distribution records from 1955 until 1985 are missing. Thirty years is a long time. The latest water distribution drawings for El Toro are from 1986. The only well on this drawings was Irvine Co. Well #55. The only thing for sure is that by 1986, there were no El Toro base wells in production.[7]

Purchase of Municipal Water

The Navy purchased a quantity of softened water from the Metropolitan Water District in 1951. The MWD Annual Report for 1951 stated that MWD contracted to supply 1 cubic foot per second of softened water to El Toro and the Santa Ana Air Facility or about 450 gallons per minutes from both bases.

From the information obtained through FOIAs to the Navy, we were able to piece together a scenario of what happened to the Navy wells and the reasons for the early purchase of municipal water.

MY “back of the envelope” calculations show that MWD’s 1 cubic foot per second of softened water equals about 450 gallons per minute for BOTH bases. This was not enough water to abandon the El Toro wells. The Navy’s pumping records show the maximum combined flow from the Navy’s four wells at El Toro in 1949 was 900 gallons per minute.

Based on the relatively small quantify of water purchased from MWD in 1951 and the 1954 water distribution engineering drawing, the facts support that the base wells were in production after the early municipal water purchase.

An annexation by IRWD of the area served by MWD forced the Navy to enter into a contract with them.[8] In July 1969, the Navy negotiated a municipal water services contract with the Irvine Ranch Water District. This contract required IRWD to make available to El Toro 3,500 gallons of water per minute. The estimated daily demand in 1969 was 1,200 gallons per minute. The Navy was not obligated to purchase this quantity of water. IRWD contract remained in effect until the base closed in July 1999. A FOIA request for a copy of the official contract file was denied by the Navy. The contract file could not be located.

In 1985, all of the water supply lines into the San Joaquin housing development (300 units) had to be replaced because of corrosion. TDS (“salts”) levels in the shallow aquifer were >500 ug/L. According to an informed source, San Joaquin was constructed in the early 1970’s. The corrosion to the unit’s water supply lines could not have been caused by softened municipal water from the MWD or follow-on contract with the Irvine Ranch Water District but could have easily come from the Navy base wells.

Over time, TDS in the well water would have caused service disruptions and costly repairs to well pumps and other equipment. At some point and as late as the 1970s or even the early 1980s, the costs of repairs and service disruptions would have forced the El Toro to abandon the wells.

What do I mean? Well, the ‘fine print’ in the IRWD contract stated that “the Government is in no way obligated to use, nor is it restricted to the above estimated requirements [1,730,000 gallons per day]. Why would the Navy purchase municipal water from IRWD in 1969 if it didn’t need this water? The answer is the Navy had no choice, if it wanted municipal water. An annexation by IRWD of the area served by MWD forced the Navy to enter into a contract with them.[9]

While the effective date of the IRWD contract was July 1, 1969, the terms of the contract gave IRWD an additional 120 days to make the necessary connections and supply main improvements and until January 1, 1970, to make the new 12 inch interconnection MWD and Orange County Feeder Number 2 and the existing 18 inch MCAS El Toro supply main.

What is even more intriguing is the provision in the 1969 IRWD contract that required the water district to pump water from the Santa Ana Air Facility wells to El Toro, if “there’s any interference with or curtailment of water services under this contract resulting from the fact the Government property is not within the service area of the Contractor’s [IRWD] District.”

The official government contract file is missing so we don’t know the reasons for this stipulation. Did the Santa Ana Air Facility’s wells have more capacity? Were El Toro’s wells contaminated? Did the high levels of total dissolved solids (“salts”) in the SGU make the sole use of El Toro’s wells undesirable? There’s no question that the Navy didn’t want to rely on El Toro’s wells.

According to the IRWD, “the groundwater in the Irvine area outside the plume of contamination contains a higher level of salts than is allowed in drinking water. This salt content comes from the natural geology of the area and the past agricultural use of the land.” Others may disagree, but we believe the issue for the Navy was the high levels of TDS in the aquifer under El Toro and the corrosive effects of TDS (“salts”) on El Toro’s water distribution system. In fact, that appears to be the most logical justification for the award of the 1951 MWD contract when the El Toro wells were less than 10 years old.

We don’t know the locations of the well screen intervals (except for Navy Well #4), but it’s possible that the Navy wells were pumping hard water from the SGU. The Total Dissolved Solids or TDS (‘salts”) levels in the SGU were very high (from 500 ug/L to 1,000 ug/L). Because of the high levels of TDS (“salts”) in the water from the SGU would have a corrosive effect on the base water distribution system, causing service disruptions and repairs. The MWD contract for softened municipal water was more likely than not intended to blend the hard water from the wells and reduce the corrosive effects on the water supply system.

The Navy had no explanation for what happened to the IRWD contract file, which remained in effect until the base was sold in 2005 and should have been available.

To make matters worse, there was an unexplained gap in water distribution drawings between 1954 and 1985 and no record of the dates the base wells were abandoned by the Marines.

Navy Spins Facts

In an August 2008 Fact Sheet published on the web, the Navy noted that TCE is not present in the Principal Aquifer (PA) under the base “at concentrations that exceed cleanup goals” because an Intermediate Zone of clay 70 to 140 foot-thick prevents vertical movement of water and contaminants from the SGU.

Sounds good but the Navy left out the fact that their consulting engineer reported TCE from a water sample of Navy Well #4 in excess of the EPA Maximum Contaminant Level, at least 40 feet of the well screen interval in the contaminated SGU, no follow-up inspections to locate the well screen intervals for the other Navy wells before sealing them, all of the original well construction drawings lost, and a major TCE plume cutting a path right through the base wells.

Ignoring these facts, the Navy emphasized the depths of the Navy’s six wells from 440 feet to 645 feet bgs as if this protected the wells from contamination. The depth of the wells was meaningless if the well screens were in the contaminated SGU.

The Navy Fact Sheet didn’t mention that a sample taken from Navy Well #2 prior to its destruction in January 2007 found very high levels of petroleum product in the well probably from leakage from a nearby UST (Underground Storage Tank).

The Navy Fact Sheet didn’t mention that Navy Well #1 was formerly an agricultural well (Irvine Co. Well #57) and may have been constructed like Irvine Company Well #55 where TCE was found during an inspection by the Orange County Water District in 1985. The difference is that Navy Well #1 was in the foot print of the TCE plume while the Irvine Company Well #55 was not.

My communications with the Naval Facility Engineering Command Southwest (San Diego) were professional but left no doubt where the Navy stood on the issue of the Navy’s base wells.

The Navy’s message was clear. The Navy dismissed any contamination of the well water, citing the fact that all the Navy wells went deep into the uncontaminated principal aquifer under the base, which was separated by 70 to 140 foot thick clay interval, named the Intermediate Zone. This clay barrier prevented any downward vertical movement of groundwater and organic solvents like TCE, PCE, vinyl chloride, and benzene, all of which contaminated the shallow aquifer under the base. In addition, the Navy noted the early purchase of municipal water from the Metropolitan Water District in 1951 and lack of pumping records after December 1950. The implication was that the base wells were not needed when municipal water was purchased from MWD.

Salem-News’ Conclusions

Water in Southern California is both scare and expensive. From the information obtained through FOIAs to the Navy, we were able to piece together a likely scenario of what happened to the Navy wells.

The Navy constructed six wells at El Toro. Only 4 of the wells were productive. All of the Navy wells were in the footprint of the TCE plume. TCE in the SGU ranged from 50 ug/L to over 500 ug/L or 10 to over 100 times the EPA acceptable level of 5 ug/L.

El Toro’s wells were not abandoned in 1951 when the Navy purchased softened municipal water from MWD. El Toro’s water distribution drawings in 1954 showed the Navy base wells as part of the water distribution system.

Water distribution engineering drawings are not available for the 30 years (1955 to 1985).

The latest El Toro water distribution drawing from 1986 showed only Irvine Company Well #55. Clearly, all of the Navy wells were abandoned before 1986.

The information provided by the Navy via several FOIA requests and our calculations indicates that the supply of softened water from MWD was insufficient to meet El Toro’s needs for potable water. The MWD contract provided for the delivery of one cubic foot per second of softened municipal water to both El Toro and the Santa Ana Air Facility or about 450 gallons per minute, which was exactly half of the maximum combined flow of El Toro’s four Navy wells.[10]

The MWD contract for softened water was intended to reduce the level of hardened water (from the total dissolved solids) by blending municipal water with well water.

Navy Well #4 was the first well sealed in 1998 and the only well inspected to determine the location of the well screen aquifer. The consulting engineering reported that the well screen was a series of vertical slots hand cut by torch from 210 feet below the ground surface (bgs) until the bottom of the well at 494 feet bgs. Since the shallow contaminated aquifer went to 250 feet bgs, this meant that about 40 feet of the well screen was in the contaminated aquifer. In 1995, a sample of the water in this well contained 12 ug/L of TCE. TCE entered this well through the well screen in the contaminated shallow aquifer.

IT IS REASONABLE TO BELIEVE THAT THE OTHER NAVY WELLS WERE CONSTRUCTED IN THE SAME MANNER AS NAVY WELL #4. WITHOUT THE ORIGINAL WELL CONSTRUCTION DRAWINGS, ONLY A PHYSICAL INSPECTION OF THE WELLS COULD DETERMINE THE LOCATION OF THE WELL SCREEN INTERVALS. THE NAVY HAD THE OPPORTUNITY TO INSPECT ALL OF THE WELLS BUT FAILED TO DO SO.

Once Well #4’s well screen was found in the contaminated SGU, the Navy should have made reasonable efforts to inspect the remaining wells, too. Failure to do so, places a cloud over the Navy’s well destruction process, suggesting the possibility of a cover-up.

The Navy’s engineers did not have the original well construction drawings, the first Well sealed was visually inspected, the inspection found 40 feet of the well screen in the contaminated SGU and TCE was found in a sample of the well water.

Additional support for Navy wells screens in the contaminated SGU was the need to purchase softened municipal from two water districts. High levels of total dissolved solids (“salts”) are found in the SGU. Corrosion of water supply lines from high levels of TDS would justify the early purchase of softened water from MWD. The clay barrier (Intermediate Zone) prevented downward migration of water, TDS and organic solvents. Where did the hardened water come from? It’s reasonable to conclude that the remaining Navy wells had portions of their well screen intervals in the shallow contaminated SGU like Well #4, allowing some level of organic solvents like TCE, PCE, and benzene into the base’s water supply.

The IRWD contract remained in effect until the base was sold in 2005. A FOIA request for a copy of the official contract file was denied by the Navy. The IRWD contract file was missing.

It’s possible that some or all of the base wells continued to function much later in time. The San Joaquin housing experienced extensive corrosion in its water supply lines. The units were build in the early 1970s and all of the water supply lines had to be replaced in 1985. After July 1969, the IRWD municipal water supply contract supplied water to El Toro. The only possible source of hard water on the base was the base wells. However, without copies of the water distribution drawings from the 1970s, the continued use of the base wells can’t be confirmed.

Over time, TDS in the well water would have caused service disruptions and costly repairs to well pumps and other equipment. At some point and maybe as late as the 1970’s but definitely before 1986, the costs of repairs and service disruptions would have forced the base to abandoned all of the Navy wells.

IS THIS CONCLUSIVE PROOF THAT WELL WATER CONTAMINATED THE EL TORO’S WATER DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM? NO, BUT THE NAVY AND MARINE CORPS WOULD BE HARD PRESSED TO EXPLAIN ALL OF THE MISSING DOCUMENTATION AND COUPLED WITH THE NAVY’S DOCUMENTED CONTAMINATION OF TWO OF THE FIVE NAVY WELLS (WELL #4 AND #2), I DON’T THINK YOU’D FIND ANY VOLUNTEERS TO DRINK THE WELL WATER TODAY.

[1] The two MWSG-37 hangars in the southwest quadrant were designated as Bldgs. 296 and 297. As a Marine in the 1960s, Bob O’Dowd worked and slept on duty watch in the North mezzanine of Bldg. 296.

[2] See paragraph 5.2, EPA Record of Decision, MCAS El Toro, 9/29/97.

[3] Marine Wing Service Group 37 was activated in July 1953 as part of the 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing (MAW) at Miami, Florida. The 3rd MAW relocated during September 1955 to El Toro, California. In April 1967, the group was re-designated as Marine Wing Support Group 37. The group relocated during October 1998 to Miramar, California. Under its current configuration, MWSG-37 is composed of four Marine Wing Support Squadrons and Headquarters Company that provide the 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing and Marine Expeditionary Force (I MEF) with Aviation Ground Support (AGS). The group’s subordinate Marine wing support squadrons (MWSSs) provide 14 AGS functions.

[4] As part of a settlement in District court in October 1949, the government paid the Irvine Company $950,000 for the 2,319 acres acquired in 1942. This settlement gave Irvine a perpetual easement for the operation, maintenance, repair, replacement and use of Well #55, its pumping plant, pipe line for production and transportation of water for their agricultural fields surrounding the base.

[5] See Appendix H for a copy of the 1951 MWD Annual Report. MWD reported that delivery of water started on June 4, 1951.

[6] See Appendix K for a copy of an April 23, 2009, email from Navy BRAC PMO confirming that only facility construction drawings that provide connections to the main distribution system were available for the period 1955 to 1985.

[7] Page 27 of the 1969 contract between IRWD and the Navy stated “this contract is entered into in consequence if the annexation to Irvine Ranch Water District of Orange County of the area of the Marine Corps Air Facility, Santa Ana, California, and the Marine Corps Air Station, El Toro, California, as set forth in Resolution No. 1968-25. The CERTIFCATE OF FILING is recorded in the Office of the County Recorder, Orange County, California, Document 21034, Book 8766, page 631 through 640 dated October 24, 1968.”

[8] Page 27 of the 1969 contract between IRWD and the Navy stated “this contract is entered into in consequence if the annexation to Irvine Ranch Water District of Orange County of the area of the Marine Corps Air Facility, Santa Ana, California, and the Marine Corps Air Station, El Toro, California, as set forth in Resolution No. 1968-25. The CERTIFCATE OF FILING is recorded in the Office of the County Recorder, Orange County, California, Document 21034, Book 8766, page 631 through 640 dated October 24, 1968.”

[9] I did some back of the envelope calculations for the municipal water services contract with MWD. The MWD contract provided for the delivery of one cubic foot/second of water for both El Toro and the Santa Ana Air Facility. The United States Geological Survey defines cubic foot per second (cfs) as “the flow rate or discharge equal to one cubic foot of water per second or about 7.5 gallons per second.” Converting the MWD’s one cubic foot per second into gallons equals about 648,000 gallons/day, (7.5 x 60 x 60 x 24) or about 450 gallons per minute, which is about half of the maximum combined flow of the Navy’s wells of 900 gallons per minute for El Toro alone.

Robert O’Dowd served in the 1st, 3rd and 4th Marine Aircraft Wings during 52 months of active duty in the 1960s. While at MCAS El Toro for two years, O’Dowd worked and slept in a Radium 226 contaminated work space in Hangar 296 in MWSG-37, the most industrialized and contaminated acreage on the base.

Robert is a two time cancer survivor and disabled veteran. Robert graduated from Temple University in 1973 with a bachelor’s of business administration, majoring in accounting, and worked with a number of federal agencies, including the EPA Office of Inspector General and the Defense Logistics Agency.

After retiring from the Department of Defense, he teamed up with Tim King of Salem-News.com to write about the environmental contamination at two Marine Corps bases (MCAS El Toro and MCB Camp Lejeune), the use of El Toro to ship weapons to the Contras and cocaine into the US on CIA proprietary aircraft, and the murder of Marine Colonel James E. Sabow and others who were a threat to blow the whistle on the illegal narcotrafficking activity. O’Dowd and King co-authored BETRAYAL: Toxic Exposure of U.S. Marines, Murder and Government Cover-Up. The book is available as a soft cover copy and eBook from Amazon.com. See: http://www.amazon.com/Betrayal-Exposure-Marines-Government-Cover-Up/dp/1502340003.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy