“My Life Has Been Ruined, Destroyed,” Says Susan Frasier

by Dennis Yusko

ALBANY — Disabled Army veteran Susan Frasier rides an overnight Greyhound bus alone each month to Washington, D.C., to walk the halls of Congress in search of elected officials who will support her where the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and federal courts have not.

Frasier, 60, blames her five months of Army training at Fort McClellan, Ala., in 1970 for decades of crippling health problems. She says toxic chemicals at the base poisoned her, causing her to suffer from fibromyalgia, autoimmune disorders and asthma. She underwent a

hysterectomy at age 37, and surgery to remove a life-threatening stomach blockage in 1991, when she was forced to retire from General Electric Co.

Despite her health problems and living on a fixed income, the Albany woman has for eight years traveled to the nation’s capital to press lawmakers to examine the health records of Fort McClellan veterans. She also wants state leaders to investigate past corruption of disability claims in the VA’s New York office, which has rejected her applications for monthly disability payments stemming from her military service.

Driven by a belief that the VA has abandoned her and others who served, the ex-soldier has turned into a “protester” for veterans rights. Frasier counsels others who served at Fort McClellan, some of whom have also experienced health problems that are similar to those caused by Agent Orange exposure and Gulf War Syndrome.

“My life has been ruined, destroyed,” Frasier said.

The Corinth native joined the Army as a healthy, fiddle-playing teenager in 1970. She wanted to serve at a time when women were integrating into new military roles. Like most female recruits and military police near the height of the Vietnam War, the Army assigned her to train at Fort McClellan in Anniston, Ala. “There was very aggressive recruitment for women to join the military in those days,” Frasier recalled. “They promised us a lot.”

Principal training center

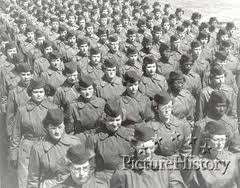

Established in 1917, Fort McClellan was the home of the Women’s Army Corps, Military Police School and the Chemical Corps. As one of the military’s principal chemical and biological training centers, some of its troops were subjected to live chemical agents in training, reports say.

The base maintained an annual average population of 10,000 troops, but the federal Base Realignment and Closure Commission voted to shut down Fort McClellan, and it closed in 1999.

At Fort McClellan, the Army assigned Frasier to its 14th Army WAC Band. The young private played percussion in a marching band and 12-string guitar in its dance band, which performed at officer clubs. Frasier remembers smokestacks emitting dark smoke and a fog-like haze, but no strange smells or tastes. She was there from July through November of 1970.

What Frasier and tens of thousands of vets who passed through the base didn’t know — and many still don’t — was that the Army’s experiments with chemical munitions on the base turned Fort McClellan into a hazardous waste site, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. But that’s not all.

Anniston, a city about the size of Saratoga Springs, grew into the most contaminated place in the nation, according to scientists. Located in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, soldiers on the 42,286-acre base drilled just miles from an enormous chemical manufacturing plant owned by Monsanto Corp., which produced and discharged tons of polychlorinated byphenyls — PCBs — into the air, soil and water for several decades until 1971, according to the EPA. Located just east from the camp is the Anniston Army Depot, which incinerated nerve gas and contaminated area soil and ground water with cyanide, lead, pesticides and more through the late-1970s, the EPA says.

PCBs were banned in 1979 due to environmental and health concerns. But the 70-acre Monsanto factory, the birthplace of PCBs, leached the chemicals into creeks and buried tons of PCB waste in two mountainous landfills, the EPA says. Residents were ordered not to grow vegetables, eat fish from rivers, even smoke cigarettes in their yards.

Monsanto and Solutia Inc., which was spun off from Monsanto in 1997, have paid more than $1 billion in damages and clean-up costs to residents of Anniston and face additional legal actions, including some lodged by Vietnam veterans. In 2005, Frasier filed a personal injury suit against Monsanto in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama. U.S. District Judge Karon Owen Bowdre dismissed it, saying Frasier disregarded court orders and deadlines and filed incorrect paperwork, according to public court documents.

The suit is one of at least eight legal actions that Frasier has lodged against corporations and governmental agencies for her health problems and alleged violations of her civil rights without the guidance of an attorney, according to court papers. She represented herself, she says, because she could not afford an attorney. All the suits were thrown out.

Frasier was honorably discharged as a specialist on Aug. 12, 1972. She retired from GE in Schenectady, and volunteers for Albany’s Office of Special Events in her spare time. She is divorced with no children, and lives on disability payments and a small pension.

Frasier is one of the first persons to demand answers about how PCBs and other toxins in Anniston impacted the health of soldiers at Fort McClellan. Her persistence is beginning to pay off.

Her years as lead spokesperson for Fort McClellan veterans with the Veterans’ Disabled Benefits Commission has become the guiding reference for Rep. Paul Tonko‘s Fort McClellan Health Registry Act. The bill would have the VA establish a list of service members stationed at Fort McClellan between 1935 and 1999, and examine their health records for toxic exposure. Tonko will reintroduce the bill to Congress this year. “We need to know the answers,” his spokesman said.

For many, the results are already in.

Like Frasier, Diana de Avila of Malta fell sick weeks after completing basic training at Fort McClellan. De Avila trained as an MP at Fort McClellan from 1983 to 1984. She, too, lost her ability to have children, and her thyroid, appendix and gall bladder have been removed. Doctors diagnosed de Avila, 45, with multiple sclerosis in 2002. “It’s been extremely difficult,” she said.

Frasier and de Avila learned randomly about the PCB threat at Anniston from a 60 Minutes news segment in 2003. De Avila also retired from GE after her symptoms grew unmanageable. The two say that many of the people they served with are ill. “I think Sue is doing a great service,” de Avila said.

Record of Pollution

PCBs and other toxic materials made Anniston the most polluted place in the U.S., said Dr. David Carpenter, director of the University at Albany’s Institute for Health and the Environment. He testified in court cases for residents around the Monsanto plant, and has studied their health patterns for the last five years. Carpenter has discovered increased rates of heart disease and high blood pressure, bone and joint pain, nervous system problems, diabetes and more.

“We think the major route of exposure was breathing the air because it was full of PCBs,” Carpenter said. PCB exposure causes cancer in animals and increases the risks of cancer, reproductive problems and autoimmune diseases in humans, he said. Nearly everyone in Anniston suffered PCB exposure, he said.

Neither Monsanto nor the EPA warned Fort McClellan vets of possible health threats, even though the company suspected by 1969 that PCBs would become “a global environmental contaminant,” and the EPA was aware of the problem since the 1970s, according to the 60 Minutes report. Neither 60 Minutes nor Carpenter’s research addressed Anniston’s veterans.

Frasier fell ill weeks after she left Alabama for Army Signal Corps School at Fort Gordon in Georgia. She was then transferred to Fort Rucker in Alabama, where she delivered death notices to families of those killed in Vietnam. Frasier’s medical records reflect her health problems. Unaware that Anniston was polluted, she returned to the area and lived there from 1973 to 1977.

Veterans say that most of the general public are unaware of the problems at Fort McClellan, but word has begun to spread on blogs and Facebook. The story, they say, has an outspoken martyr in Agnes Bresnahan. Less than three years before dying in 2009 from chemical exposure, the Army captain testified before the VA Disability Commission in Washington, D.C., that doctors at Walter Reed Medical Hospital had diagnosed her with exposure to Agent Orange, PCBs, mustard gas and sarin gas from her time at Fort McClellan. Bresnahan told the commission in 2006 that she wanted to address “the total and intentional failure of the VA in processing and approving service-connected entitlements for women and men exposed to weapons of mass destruction.”

Frasier became a lead spokesperson for Fort McClellan vets after Bresnahan’s death, said Paul Sutton, the former longtime chairman of the Vietnam Veterans of America’s National Agent Orange/Dioxin Committee. A former Marine who was exposed to Agent Orange twice in Vietnam, Sutton is an advocate for sick Vietnam-era and Fort McClellan vets.

During the Vietnam War era, the military experimented with Agent Orange, a toxic defoliant, at Fort McClellan, and stored cannisters of it near a women’s training center and barracks, Sutton said. “Virtually every woman who cycled through there in the late 1960s and early 1970s probably have had health affects,” Sutton said. He estimated that up to 6,000 women and about half that number of men were made ill by PCBs or Agent Orange at Fort McClellan during the Vietman War years, and the VA has paid out disability benefits to “probably less than 50” of them for health complications.

Unlike Frasier, de Avila receives VA disability payments because it ruled that her MS is service-connected. The VA, however, does not acknowledge that de Avila became ill at Fort McClellan, she said. It can be very difficult for older veterans to prove that their illnesses are service-related, Sutton said.

Hazardous Waste Sites

The military practiced with many hazardous materials at its bases before environmental laws took hold. More than 170 military bases in the U.S., including Fort McClellan, are designated hazardous waste sites, says the EPA, which tracks nearly 1,600 such sites nationwide. The EPA has not tested Fort McClellan for PCBs.

The military practiced with many hazardous materials at its bases before environmental laws took hold. More than 170 military bases in the U.S., including Fort McClellan, are designated hazardous waste sites, says the EPA, which tracks nearly 1,600 such sites nationwide. The EPA has not tested Fort McClellan for PCBs.

The Army says it is cleaning up munitions, explosives and sites on Fort McClellan where “contaminants” were released. The VA declined to answer questions for this article, even though Frasier signed a form allowing discussion of her confidential file.

But VA Director Bradley Mayes told the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs in 2008 that the Department of Defense had concluded that there was little or no PCB contamination at Fort McClellan. Soldiers living off-base, however, “may have been exposed to PCBs,” he said.

The VA does not support creating a health registry of Fort McClellan veterans because it is “unlikely to improve the health or otherwise benefit” them, Mayes said. He added that it would be difficult to locate personnel who served and find accurate information about their medical conditions. The VA is instead monitoring health studies being done on Anniston residents by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Mayes said. Veterans who can prove that their illnesses are related to exposure during military service can obtain a related disability claim, Mayes said. But that hasn’t been the case for Frasier.

She applied for VA disability benefits weeks after her discharge, but is still appealing her denials 39 years later. A VA hospital nurse filed Frasier’s original disability application in 1972, but did not submit necessary paperwork, which damaged Frasier’s application for benefits, she said.

In interviews and court papers, Frasier alleges that the VA has relieved itself from paying disability claims to her and other Fort McClellan veterans through phony hearings, tampering with or trashing claims and other legal maneuvers. She had spoken out about VA claims issues before 2008, when officials found widespread backdating of claims and piles of unopened mail in its New York City office.

Fraiser’s most recent legal maneuver over disability benefits is an appeal filed against VA Secretary Eric Shinseki in which she seeks to overhaul the VA disability claims system to make it what she says will be more accountable to veterans. Last month, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit became the fourth entity to rule against her.

View Original Article

“That’s a lifetime lost to process with no accountability on the other end,” Frasier said.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy