To prepare for the new Syria, people have been digging up their not too distant past, well into the pre-Ba’ath era – not to copy it, but to learn from it.

To prepare for the new Syria, people have been digging up their not too distant past, well into the pre-Ba’ath era – not to copy it, but to learn from it.

by Sami Moubayed

The pre-Ba’ath era in Syria is generally acknowledged by most people as the “golden era” of Syrian democracy.

Even radical Ba’athists who refused to admit that in the past nownod affirmatively when such a bold statement is made, acknowledging that when operating through a real democracy, the Ba’athists won an overwhelming number of seats in the parliamentary elections of 1954.

That period roughly lasted from birth of the republic in 1932 until rise of the Ba’athists in 1963. The socialists, officers and politicians of the post-1963 order often accused this period of having been elitist, feudal and unjust, concentrated in the hands of the urban notability, claiming that it was a dictatorship of the elite, representing urban Syria with no regard to its rural population, rather than a true democracy.

Now with rural Syria ablaze since March, young people are demonstrating to bring down Ba’ath Party rule. These rural districts are the same ones that produced many of the Ba’ath Party’s veteran leaders, 50 years ago. The Ba’athists came to power with the ostensible objective of empowering rural Syria – never imagining that one day they would face the most serious threat to their rule from rural areas.

Ba’ath Party rule as we have known it for 48 years is practically over. The party simply cannot survive with the same tools, rhetoric and mechanisms that it has used to rule for nearly five decades. It will be only a matter of time before all official symbols of Ba’athism start to disappear, ranging from their control over state media, youth organizations and syndicates, onto Article 8 of the constitution that designates the Ba’ath as “leader of state and society.”

The Ba’ath Party, as a grassroots organization with millions of followers and a long history, will continue to operate in a multi-party system. It would be wrong and unfair to deprive the Ba’athists of their constitutional right to run for elections, hold cabinet office or try to win a majority in parliament through the ballots. To prepare for the new Syria, people have been digging up their not too distant past, well into the pre-Ba’ath era – not to copy it, but to learn from it.

As Syria gets its new political party law, some are trying to resurrect parties from the pre-1963 era, such as the National Party of Damascus and the Aleppo-based People’s Party. The two parties were non-ideological, mirroring instead the business interests of both cities.

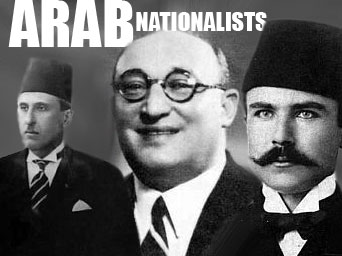

The National Party was close to Saudi Arabia and Egypt and headed by veterans like president Shukri al-Quwatli and premiers Sabri al-Asali and Fares al-Khury. These men, it must be noted, were among the finest nationalists of the Arab world in the 20th century, hailed as freedom fighters for having liberated their country from the Ottomans and the French.

The People’s Party, which came to power through the ballots in 1949-1951, was close to Iraq and it produced the last democratically elected civilian president of Syria, being Nazem al-Qudsi, who was toppled by the Ba’athists in 1963.

All of these figures are long gone, but activists are trying to rediscover them and walk in their footsteps. The initiative is being led by the sons and grandsons of an older generation of Syrian politicians who were sidelined by the Ba’athists in 1963. These two parties were all outlawed, along with five others, by the Ba’ath Party when it first came to power 48 years ago.

The photos of these historical figures are already re-appearing, on the Facebook pages of active Syrians. People are replacing their profile pictures with those of former presidents Mohammad Ali al-Abed, Shukri and Hashem al-Atasi.

Additionally, several opposition activists are related to former Syrian heavyweights, such as the grandson of president Adib al-Shishakli, the son of former prime minister Maarouf al-Dawalibi and the daughter of Sultan al-Atrash, commander of the anti-French revolt of 1925.

That is in addition to the large and influential Atasi clan of Homs, which produced three presidents – Lu’ayy and Nur al-Din (during the early Ba’ath years) and Hashem al-Atasi, one of the founders of Syria’s independence from French colonialism.

After a long absence from public life, the Atasi are re-emerging quickly on the political scene. Legal experts calling for amendment of the constitution, for example, are digging up Syria’s previous constitutions, the first dating back to 1928, trying to find a formula that combines a presidential system and parliamentary republic.

And finally, the pre-Ba’ath flag of Syria, known as the “Flag of Independence” because it was used when the French evacuated in 1946, is starting to re-emerge in street demonstrations, after a 50-year absence.

The biggest lesson to be learnt from the pre-Ba’ath era should be for the Ba’athists themselves. They were born out of a democracy in 1947 and allowed to grow and prosper in a healthy political environment during the heyday of Syria’s multi-party parliamentary system.

Back then, they had a very promising and idealistic party, filled with capable leaders, inspiring doctrine, and A-class intellectuals with an ambition that knew no bounds. Because of that, the Ba’ath managed to attract the brightest and most capable of Syrian youth during the 1940s and 1950s. At that time, Ba’ath Party veterans would tell aspiring young members that they had to be number one in order to be considered for membership.

From the 1980s onwards, however, it became the opposite: party members were given number-one status in work, pay and professional development not because of their merit or achievement, but simply because they were members in the ruling party.

This created three generations of mediocre and below-average members who rose to positions of authority in the state not because they were good, but because they were Ba’athist. More than anybody else, the Ba’athists of today need to reach back to the civility, democracy and good citizenship that characterized Syrian society prior to the March 8, 1963 revolution.

It was a period of gentleman politics; where word of honor prevailed and where good manners – in day-to-day life and political conduct, were respected and expected by Syrian society. There are so many lessons that need to be learned from that era, both for the Ba’athists and for the architects of the new Syria.

Sami Moubayed is a university professor, historian, and editor-in-chief of Forward Magazine in Syria. This article appeared in Asia Times Online on September 2, 2011.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy