Via the Defense Base Act Compensation Blog

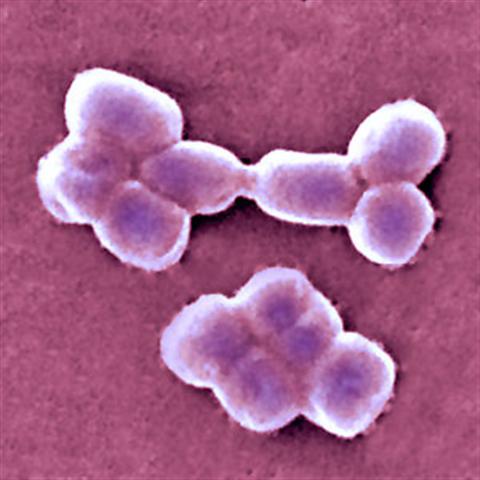

Many Injured Contractors were repatriated via the Military Medical Evacuation System which was/is badly contaminated with Multi Drug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Soldiers and Contractors alike lost lives and limbs to this dangerous Superbug.

Injured Contractors played an even larger role in the spread of MDRAb across the US and to every country of the “coalition” than did the soldiers themselves. Injured Contractors were infected in field hospitals, Landstuhl, Walter Reed, Bethesda Naval, and then transferred to Civilian Community hospitals. Civilian hospitals were seldom warned their new transfers were infected with a life threatening highly contagious bacteria.

The DoD’s usual knee jerk reaction was to cover this problem up rather than deal with it. Lie about to be exact.

Steve Silberman, Investigative Journalist for Wired, has written again, on the spread of this Superbug and the Military and “Wikipedia Journalism’s” aiding and abetting the enemy.

Is Wikipedia Journalism Aiding the Spread of a Deadly Superbug?

by Steve Silberman at NeuroTribes

Japan is in an uproar. Last week, officials at the Teikyo University Hospital admitted that 46 patients in the past year have been infected with an antibiotic-resistant bacterium called Acinetobacter baumannii, and that 27 have died. Today, the number of infected patients was increased to 53, and hospital announced that it would admit no new patients until it checks for the presence of the bacteria in more than 800 patients currently in the hospital. In a contrite press conference, hospital officials admitted that they had not promptly reported the infections to local authorities as they are legally required to do, and that this delay likely contributed to the spread of the bacteria through the wards, and to patient deaths.

Meanwhile, other Tokyo hospitals are also now reporting infections and deaths. Yurin Hospital discovered that eight of its patients — aged 59 to 100 — were colonized by the bacteria, and four of them have died. Three patients at the Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital were also infected, and one has died. The bacteria seems to be spreading rapidly through hospitals in the Japanese metropolis, aided by patient transfers, overuse of antibiotics, lack of sufficient infection control, and failure to report the infections to health authorities. Seeking to place the blame for the seemingly sudden upsurge of the bacteria, The Daily Yomiuri ominously speculated today, “Could medical tourists bring something more sinister than their own health problems with them when they come to Japan?”

Sadly, none of this is a surprise to me: not the rapid spread of the bacteria, not the deaths, and not the failure to acknowledge the problem until numerous patients had died or become colonized, and not the frantic seeking to place the blame by demonizing people from other cultures. The same pattern emerged in an epidemic of Acinetobacter baumannii infections among American and Canadian troops returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which I wrote about for Wired magazine in 2007, in an in-depth investigative feature called “The Invisible Enemy.”

Back then, it was the U.S. Defense Department officials who were slow to acknowledge rampant acinetobacter infections in the ranks, and they were not nearly as eager to take responsibility as Japanese officials have been this week. Indeed, there seemed to be a coordinated effort to mislead the press about the true source of the infections. Antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumanniiis almost always found in hospitals and other health care facilities. It is a nosocomial infection — like MRSA, Clostridium difficile, and the other horsemen of the post-antibiotic apocalypse, it preys on those who are already sick, elderly, or traumatically injured, piling agony upon agony. That’s why troops and civilians gravely wounded in war are one of acinetobacter’s favorite target demographics: all that fresh, exposed meat, left undefended by already weakened immune systems or immunosuppressive drugs. Particularly among the young — car-crash victims and the like — many acinetobacter infections go undetected, because the primary trauma alone is enough to kill the patient.

The story coming from Washington, however, was that the source of the bacteria was Iraqi insurgents who were intentionally “dosing” improvised explosive devices (IEDs) with the superbug, in the form of dog feces or rotting meat. The alternate version of the official story was that Acinetobacter baumannii lurks in the Iraqi soil itself, waiting to pounce on young American warriors like some kind of microbial jihad. In the fog of war, reporters bought these official story lines and parroted them dutifully, from CNN’s Situation Room to CBS correspondent Kimberly Dozier, who called A. baumannii “an Iraqi bacteria” (as if organisms carry passports) after barely surviving an IED attack and subsequent infection in 2006. In the military and the press, the bacteria acquired the catchy nickname “Iraqibacter,” which has a darkly ironic grain of truth to it — wounded Iraqi citizens cared for in our field hospitals in the early days of the war became infected at much higher rates than our troops, and were then released back into a country with a health-care infrastructure that had been bombed back to the Stone Age.

For more information about how the Pentagon conducted a secret war against this bacteria, see my 2007 story. But I knew when I filed it that the saga of the medical battle against Acinetobacter baumannii was just beginning. Since my story ran, there have been numerous outbreaks of the superbug in hospitals in Europe and Asia, with scores of patients — both military and civilian — left dead.

In time, the “dosed IED” story slowly faded away. But one aspect of the misleading press coverage of the bacteria refuses to die: the notion — repeated by the Mainichi Daily News and other Japanese papers this week — that multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii is commonly found in water and soil. This notion — that A. baumannii is nearly ubiquitous in the natural world — has been reinforced by everyone from local TV news stations to the New York Times.

Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii is not commonly found in water and soil. It is found in hospitals and clinics, where the tenacious organisms earn their resistance to the best drugs we can throw at them; it is particularly prevalent in intensive-care units, lurking among those moist places where medical equipment enters the body, such as catheters and breathing tubes.

To put it another way, Acinetobacter baumanniiis not a “wild” superbug. It is a thoroughly domesticated superbug, inadvertently trained and evolved by us, living alongside us in a terrible synergy, and thriving on the spoils of war, aging, disease, and the failure to implement proper infection controls.

Beyond misleading shaggy dog-poop stories from Pentagon spokespeople, the source of this problem in journalism may be tragically mundane. Acinetobacter in general — that is, not baumannii — is one of the largest and most diverse genera of bacteria on the planet, comprising more than 30 distinct species, including Acinetobacter baylyi and Acinetobacter haemolyticus. Right up at the top of the Wikipedia entry for Acinetobacter, Googling journalists on deadline are informed that the bacteria is an “important soil organism.” While that’s true of some members of the genus, it’s not true of the species causing these infections. You have to get down in the fine print to realize that A. baumannii — the evolutionary sequel — is a whole other kind of beast, native to hospitals, and worthy of its own Wikipedia entry.

This confusion has resulted in hundreds of news stories — and even a fact sheet [PDF link] put out by the Infectious Diseases Society of America — claiming that Acinetobacter baumannii is “commonly found in water and soil,” when the scientist who discovered antibiotic resistance in the organism, Lenie Dijkshoorn, a senior researcher at Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands, told me when I interviewed her for my Wired story, “My colleagues and I have been looking for Acinetobacter baumannii in soil samples for years, and we haven’t found it. These organisms are quite rare outside of hospitals.”

So what’s the big deal? The big deal is that errors in medical journalism — particularly ones that proliferate everywhere in big media virtually unchallenged — can lead to bad medicine. I felt a chill pass over me when I read a 2006 paper in the Canadian Medical Association Journalthat quoted Major Homer Tien, a Canadian trauma surgeon serving in Afghanistan, saying that because he believed the windblown desert sand carries A. baumannii, “There’s talk of building an antechamber to the hospital, so you’d have a double set of doors, to help keep the sand out.”

In any health-care setting, infection-control resources are stretched thin. Hospitals — on the front lines or back home — simply cannot afford this kind of confusion. Every news story that echoes the false claim that Acinetobacter baumannii is “commonly found in soil and water” is part of the problem.

A citizen journalist named Marcie Hascall Clark — the wife of a contractor who picked up the bacteria in a hospital after being wounded in Baghdad — has been sounding the alarm for years, a voice in the online wilderness. By 2007, when I wrote my Wiredstory, many physicians in the military had already figured out what was really going on, and were starting to implement strict protocols — including rebuilding the field hospitals, increasing disease surveillance, and isolating infected and colonized patients — to minimize colonization and new infections among wounded troops. The US medical establishment and smart science bloggers like Maryn McKenna, author of Superbug, have also awakened to the growing threat of this particularly nasty and adaptive organism. “In the all-star annals of resistant bugs,” McKenna wrote in June, “A. baumanniiis an underappreciated player.”

Much of the media, however — from America to Japan — has yet to catch up.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy