DISCLOSURE: VT condemns the horrific tragedy committed by the NAZI Party against Jewish Citizens of Europe during Word War II known as the "Holocaust". VT condemns all racism, bigotry, hate speech, and violence. However, we are an open source uncensored journal and support the right of independent writers and commentors to express their voices; even if those voices are not mainstream as long as they do NOT openly call for violence. Please report any violations of comment policy to us immediately. Strong reader discretion is advised.

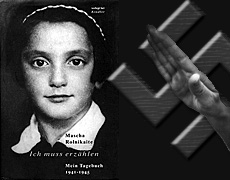

Holocaust Chronicler’s Story Must Be Told

Holocaust Chronicler’s Story Must Be Told

By Manuela Muhm

A little girl is dancing on the stage, with the ease of a butterfly gliding from flower to flower. All of a sudden the sky darkens and a huge lurking spider is slowly approaching its prey. The little girl is scared, tries to escape, she is writhing in pain, pleading for mercy, crying her heart out. But the threads of the dark net are pulling together mercilessly, leaving no room for escape. The little girl breaks down, as if a bullet hit her.

For the then 14-year-old Masha Rolnikaite, watching this scene as it was performed by the dancing class of the Vilnius Ghetto, it went without saying that the lurking spider embodied fascism, which had spread over most of Europe. Like millions of Jews, she had been captured in the cobweb of fascism, out of which only several thousands would escape.

“The reason I survived is mere chance; I was lucky not to be among those who were slain by the Nazis,” Rolnikaite said, sipping tea as she retold her terrible story in her apartment in St. Petersburg, Russia. Outside the snow began to fall lightly and it was hard to imagine what hell this woman had gone through 64 years ago……..

More than six million Jews perished at the hands of the Nazis. A lot has been written about the Holocaust, some may even say it is time to close this bleak chapter of 20th century history. But while the fate of Jewish communities in Germany, the Netherlands or Poland is well covered, little is known about the obliteration of Jewish culture in the Baltic States.

Across Lithuania some 200,000 Jews – more than 94 percent of the pre-war Jewish community – fell prey to the gruesome hatred of Hitler and his willing accomplices – a higher percentage than in any other country Hitler occupied. By the end of 1941, even before the Endlösung, the “Final Solution”, was decided in Berlin, Lithuania was declared judenfrei (free of Jews), a Nazi euphemism for successful ethnic cleansing of an area by deportation or murder.

SS-Standartenführer Karl Jäger kept a meticulous record of the annihilation of the Lithuanian Jewish community; the place and exact date of death of all victims were listed as if these figures belonged to an accountancy department.

The report concluded with the figure 137,346. “In Lithuania there are no more Jews, apart from Jewish workers and their families. The distance between from the assembly point to the graves was on average 4 kilometers to 5 kilometers, “the report said.

Before the war, Vilnius was famously dubbed the “Jerusalem of the North” as it had developed an extremely rich Jewish culture. All across Europe Vilnius earned praise for its thriving Yiddish-language theaters, libraries, schools and its Talmudic scholars. Jewish Lithuanians called themselves “Litwakes,” many becoming famous beyond the Lithuanian borders.

Apart from Lithuanian Jewish writers like Abraham Mapu, Abraham Sutzkever or Eisik Meir Dick, the “Jerusalem of the North” was also the birthplace of numerous other famous artists. Violinist Jascha Heifetz and Mark Chagall, the world-famous painter, were Litwakes, to name just a few.

IN THE CLUTCHES

OF THE BLACK SPIDER

The now 78-year-old Rolnikaite is not only a contemporary witness of Hitler’s crimes, but also recorded her experiences in a diary, which has become an important document of Vilnius’s Jewish past. Keeping a diary was common at the time.

“We confided our little worries and teenage problems to our diaries, like, for example, what grade we got, what book we read, and what movie we watched,” she said.

With the invasion of the German troops on June 24, 1941, she continued keeping track of her everyday life out of habit. Rolnikaite considers her diary not “a heroic deed,” as people often like to think, but as a child’s wish to tell her fate.

“In our classroom a large map of the world hung on the wall. And I understood that there were countries where there was no Hitler. And the people living in these countries had to learn the truth about what was happening to us.”

The threatening black spider with the swastika on its back was weaving its lethal net slowly. While Masha’s father was able to flee the country and join the Red Army, Masha’s mother was trapped with her three daughters and one son. Immediately after the German invasion, the first orders – stating that Jews were not allowed to walk on sidewalks; that they had to sew the yellow Star of David on all visible clothing, and forbidding Jews to enter public places such as shops or cafes were issued.

“At first, I felt not so much afraid as ashamed to go out onto the street,” Rolnikaite remembers. “My classmates and teacher walked on the sidewalk and I had to walk on the street like a horse.”

On her 14th birthday, Masha decided to wear her light blue silken dress. She left home without her yellow star and ran through the narrow streets of Vilnius to her hairdresser to have her hair cut. It would be the last time she strolled the streets of her beloved city. In September 1941, the family was forced to move into Ghetto 1. The German troops had established two Ghettos, Ghetto 1 and Ghetto 2, separated by Deutsche Gasse, the German Lane. Ghetto 1 was designated for craftsmen and workers with permits, and Ghetto 2 was to be for all others – the elderly, workers without permits, and orphans. Six weeks later, Ghetto 2 was eliminated. “What does ghetto mean?” the 14-year-old Masha asked. “What is life like in a ghetto?”

Living in the ghetto meant dilapidated housing, poor hygiene and unbearable congestion. It was calculated that in the 72 buildings in Ghetto 1, the average living space per person was 1.5 to 2 square meters. The killing never stopped.

In nightly Aktionen (raids), German Einsatzkommando (task force) units tried to hunt down Jews not holding yellow certificates, which had the status of work permits. Those arrested were later marched to the Ponar forest eight kilometers away, shot, and buried in mass graves. Ponar became the symbol of horror. More than 70,000 Lithuanian Jews, most of them from Vilnius, were murdered at this place.

The Germans did not get their own hands dirty when carrying out their bloody business.

“Lithuanians worked as guards. In general, the Germans only gave orders. Lithuanians did the shootings. They got a work permit and were allowed to keep money and other valuables they found on the dead bodies”, Rolnikaite remembers.

As testified by the reports of Einsatzkommando unit A, the rapid annihilation of the Jews of Lithuania was only made possible because of the willing participation of the local population. Exploiting the superstitious anti-Semitic prejudices of the local people and their hatred of the Soviets, the Germans made use of these willing collaborators to round up and kill Jews. In Vilnius, Lithuanians roamed the streets, capturing Jewish men and hauling them away, supposedly for work. The activities of these Lithuanian auxiliaries were so in tune with German plans that by the end of July 1941, 20 local police battalions were formed. Between a half and two-thirds of all Lithuanian Jews were killed by local militia.

But even in the darkest night there is some glimmer of hope. The teacher Henrikas Jonaitis, who provided Masha and her family with food and moral support, was just one of many Lithuanians who assisted the Jewish community and tried to relieve their plight at the risk of their own lives. An Austrian soldier, Anton Schmidt, hid Jews in the basement of a mattress workshop and arranged for their transfer to Belarus in military trucks. The German secret police, the Gestapo, executed him.

Rolnikaite does not like generalizations that describe whole ethnicities in terms of black and white. “Just as it was completely untrue that all Jews were bad, not all Germans were barbarous butchers. It is wrong to generalize.”

Under the leadership of Itzik Witenberg the United Partisans Organization, or F.P.O. attempted to rouse the population to fight their persecutors. “All the roads of the Gestapo lead to Ponar. And Ponar is death! Let us not go as sheep to the slaughter!” its leaflets said. Yet their armed resistance was ineffective and on July 16, 1943, Witenberg was forced to hand himself over to the SS.

Another form of resistance was offered by the means of art.

“Art is spiritual resistance,” Rolnikaite says. “At the beginning of 1942, some intellectuals gathered to found an arts organization to force people not to lose their pride in themselves.”

This organization created a choir, a theater, dancing classes and an orchestra.

“It was difficult to run the choir. After every Aktion some singers were missing and they had to be replaced by new ones. People were tired after their hard work, and many were in mourning and did not want to sing. There was also a library, and people would read. I used to sit on the staircase of our house and read. I just wanted to escape from this nightmarish reality.”

Despite the Jews’ hope of imminent liberation by the approaching Red Army, the ghetto was emptied on Sept. 23 and 24, 1943, and in the general confusion Masha was separated from her mother and brother and sister. “Goodbye, my child! At least you will live! Take revenge for our babies!” This was the last time Masha saw her mother. Taiba Rolnikaite and her younger siblings Rajele, 9, and Ruwele, 7, were murdered, in all probability, in a concentration camp. Rolnikaite has never found out where they perished.

Masha and 1,700 other women considered capable of work were transferred to the infamous concentration camp Kaiserwald north of Riga, and later to the nearby concentration camp Strasdenhof. The young girl was to experience sadistic tortures, hunger and forced labor. When the Red Army was close to Riga, the concentration camp was liquidated and the imprisoned women were brought to the Stutthof extermination camp near Danzig, which is now the Polish city of Gdansk.

At Stutthof, the furnaces worked day and night. The prisoners’ shacks were unheated and had no water. When a typhoid epidemic broke out, numerous women did not survive the fatal disease. In her diary Masha remembers these days of horror. “It is a genuine death camp. The Germans do not bother to keep order. There are no roll calls any more: they are indeed afraid of entering the shacks.”

Masha’s diary ends with the evacuation of Stutthof and the three-week march through abandoned territory. When the women were gathered in a barn to be burned, a vanguard of the Red Army arrived and liberated the prisoners. By that time Masha weighed only 38 kilograms. A Soviet soldier carried Masha out of the barn. “Do not cry little sister. We will not let evil happen to you ever again”.

BEGINNING OF A NEW LIFE

In March 1945, Masha was given a second life. She immediately returned to Vilnius and learned that her father and eldest sister had survived the war. “It was very hard for me to get back to normal life. When I went out on the street, I unconsciously sought the yellow star. I had to force myself to walk on sidewalks. If a person gave me a menacing look, I got scared and thought what he might do to me”.

Masha’s father wanted her to go back to school to catch up on her missed education. “At first, I refused to go to school. Why is it important to know mathematical formulae or where the Mississippi lies”. But then she gave in, attended evening classes and later enrolled at the Gorky Literature Institute in Moscow.

Masha soon started to restore her diary. She had destroyed her notes when the Aktionen started to occur increasingly often. If her notes were found, the Germans would kill the whole family, her mother had warned her. Masha burned her diary and tried to keep it in her head. When dragging heavy buckets filled with water at a farm, she counted the number of buckets to train her memory. Later on, in the Strasdenhof concentration camp, she ran over her experiences in her mind while dragging heavy stones.

“This helped me to preserve my sanity. And long after the war, when I was studying at the institute as an external student, I never finished studying on time and got little sleep the night before exams. If I could remember 10 telephone numbers and some part of the diary in the morning, I knew that my mind was working and I took the exam. If not, I went to bed again to have some more sleep.”

Therefore, her diary reads like prose, without dates. But when she was creating it she had not intended to publish it. It was important to survive, to look ahead to the future even when dark clouds were looming on the horizon.

In her introduction to the German edition, the German journalist Marianna Butenschön described Rolnikaite’s diary as written from the point of view of a child who had grown up overnight.

“This is why the text is so interesting, and Masha was a good observer,” she writes.

Rolnikaite was not the only chronicler of the ghetto in Vilnius but the obliteration of the Litwakes was also documented by Hermann Kruk, director of the Ghetto library, and by the journalist Grigory Schur. Their observations confirm each other’s versions.

Ninety percent of Rolnikaite’s diary, restored from her memory, corresponds with to the original diary, Butenschön says in the introduction.

The remaining 10 percent of non-identical text concerns “individual words, expressions or idioms but do not concern facts”, Rolnikaite said.

After the German troops had been defeated, Jewish cultural life started to revive in Vilnius. Abraham Sutzkever and Shmerke Kaczerginski founded a Jewish cultural and arts museum in the building that formerly housed the ghetto library.

The Jewish actor Solomon Mikhoels, who was also director of the Jewish theater in Moscow and president of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, visited the museum.

Mikhoels learned about Masha’s diary and borrowed it from her. He stayed up all night reading it, but explained afterward that it would shouldn’t be published because the Jewish community shouldn’t shed tears about what had happened in the past but build up a new culture for the future.

Mikhoel’s reaction aroused perplexity and a terrible foreboding among the Litwakes, which would soon to be fulfilled. On Jan. 13, 1948, the Jewish community was shaken by news that Mikhoel had died. As it turned out later, Mikhoels had been murdered by the NKVD secret police. His death marked the beginning of the Stalinist persecution of Jews, who were defamed as “homeless cosmopolitans.”

A large number of Jewish intellectuals were arrested and deported to Siberia. The Jewish theater in Moscow was closed, the streets and lanes in the Jewish quarter in Vilnius were renamed and Jewish tombstones were used as construction material all over Vilnius.

“The Jewish community had collected money to put up a memorial to the Jews murdered at the execution site of Ponar,” Rolnikaite said. “In 1952, the memorial was leveled to the ground one night and replaced by a rather modest obelisk devoted to all Soviet victims of fascism. There was not a single word about the Jews.”

With Stalin’s death, the wave of anti-Semitism subsided and Masha submitted her diary to the publishing company for scientific and political literature in Vilnius. Some months later, she received the required report.

For Masha the assessment read “like a death sentence”. The diary was described as not written from the correct class position – the Jewish Council was depicted in too positive a light, and Soviet partisans were not given the deserved attention. First, Masha refused to carry out the required changes, later she was prepared to compromise.

The famous Jewish-Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg, who had been awarded the Stalin prize and was notorious for his biting, strongly anti-German writing, first agreed to write the introduction of the Russian edition but later changed his mind. The manuscript of his sixth book had been returned to him with more than 134 comments, out of which he only considered 60. Ehrenburg feared that he would only harm her if he wrote the introduction.

It was not until 1963, almost 20 years after the end of the war, that her diary was printed in Yiddish under the title “I Must Tell.” Two years later a censored Russian translation was published. Moscow sold the manuscript to foreign publishing houses and boasted that the Soviet Union had its own Anne Frank.

“The Diary of Anne Frank,” written by a teenage Jewish refuge whose family hid in the Netherlands, is one of the most widely read tales of the Holocaust. Frank’s family were betrayed and she perished in the concentration camp Bergen-Belsen.

Rolnikaite does not like to be compared with Frank. “Anne Frank is famous through world. And I understand that her name was invoked to promote my book. But I do not want to be compared to her. Anne Frank is dead but I am still alive.”

Rolnikaite’s book was translated into 18 languages and published in 24 editions. But the shadows of her past have not ceased to hunt her. And she feels bound to tell her story over and over again by reading her diary to the public and visiting schools to talk to the younger generation about her experiences.

“When I was first invited to visit East Germany after the publication of the German edition, everybody asked me why I had agreed to take this trip. But I answered that I had to go to Germany. I needed to distinguish the Germany I got to know from the Germany of today”.

HUNTING THE SHADOWS

OF THE PAST

In the meantime, Rolnikaite has visited Germany five times. Her latest trip was to Nienburg, a small town in western Germany, where she was invited to talk about the Holocaust to pupils of a German high school. Although traveling has become difficult for the 78-year-old woman she had accepted the invitation. “The pupils there really did not know anything. Only one boy said that he read “The Diary of Anne Frank.” But they were interested and asked questions.”

Some pupils asked her whether she could forgive the German people for what happened to her. Rolnikaite does not experience any hatred. “I cannot forgive the SS people. But I do not feel any hatred towards other Germans.”

At the age of 14, Masha had given herself the promise “to enjoy every single minute of my life if I survive all this”. Looking back, she admits that she has not always been able to keep her promise – especially in moments when her fight against “the lurking black spider” appeared to be fruitless.

In 1967 for instance, Franz Murer, the “expert on Jewish affairs” who supervised Vilnius from 1941 to 1943, for which he was also called “The Butcher of Vilnius,” was acquitted by an Austrian court. Rolnikaite cannot understand this decision as she herself had witnessed Murer murdering numerous Jews.

And today fascism seems to have gained new power, even in the city where she lives, St. Petersburg, where thousands died during the Siege of Leningrad from 1941 to 1944.

“It is incomprehensible that the grandchildren of those who died under the Nazi regime join racist movements. Once, my husband and I were going home by metro when we noticed a young man, dressed in a black uniform with a swastika symbol on his right sleeve. Nobody paid any attention to him.”

The fact that present-day Russia is experiencing a strong swing to the right is often overlooked by the West.

A right-wing subculture has been developing in most major Russian cities and this trend does not seem to be coming to an end. On the contrary, right-wing extremism has been continuously spreading since the authorities not only do little to control them, but critics say they even support it. The police harass people with Caucasian and Asian appearances by random passport controls, extort money from their victims, beat them up and abuse them. Racially motivated attacks are often ignored or classified as hooliganism.

Friedrich Schiller announced in his “Ode to Joy” that “all humans will become brothers.”

In Rolnikaite’s opinion this wish will not be fulfilled.

“It seems that there is something evil in the human soul. Why did people join the SS? Some people obviously are defective. Bruno Kittel, for instance, was an actor and musician before he joined the SS. Strange things happen when you give a person power.”

Rolnikaite has been writing books her whole life. And all of them revolve around the one topic – the Holocaust of the Jewish community. Writing has become her way to survive.

“I want to give those a voice who did not survive the Holocaust. By talking about my experiences I feel I am doing something useful … I am contributing to the fight against racism and exclusion.”

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy