Poisoned veterans got empty promises

Poisoned veterans got empty promises

By: David Zeman

On the morning of March 10, 1993, as a blizzard barreled toward the East Coast, two senior officials from the Department of Veterans Affairs sat before a congressional panel and explained how the VA planned to track down thousands of World War II veterans exposed to hazardous chemicals.

“There is no doubt this is a dangerous occupational exposure,” Dr. Susan Mather told the House subcommittee. “So we will get their current names and addresses from IRS and then we will notify them directly of their exposure and ask them to come in.”

Nearly two years had passed since the Pentagon first acknowledged that it deliberately injured at least 4,000 soldiers and sailors in secret chemical tests during World War II. The Pentagon pledged to search for lists of these veterans for the VA.

Mather, a VA assistant chief of environmental medicine and public health, and John Vogel, deputy undersecretary for benefits, assured the congressmen the VA would actively pursue the men. “One cannot lose sight of the fact that medical care may be needed for these people,” Vogel said.

Rep. Michael Bilirakis, R-Fla., pressed the point: “You are not waiting; you are not sitting back, basically, and waiting for claims to be filed by them?”

“Oh, no, not at all,” Vogel said.

Breaking the silence

Just north of Washington, a veteran of the 1st Chemical Casual Company, wracked with skin cancer, felt the jolt of history.

Lee Landauer picked up his newspaper in suburban Baltimore one morning and learned – for the first time, he said – that the military misled his unit about the dangers of the chemical tests; that the poisons used on him in 1943 could kill him 50 years later. He learned something else, too: Washington stood ready to help.

Landauer felt liberated. The secret was out; his sacrifice acknowledged. And, for the first time in a decade, the cancer that had picked at his face, arms, neck, back and chest could be explained.

“They made it sound like the government wanted to see me,” Landauer said.

He pulled on his jacket and headed downtown to file a claim.

For the aging warriors of the 1st Chemical Casual Company, the flurry of attention the World War II program received in Washington in the early 1990s produced a rush of memories, and a disturbing new lens through which to view them.

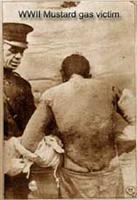

As young recruits in 1943, they were locked in gas chambers with mustard, lewisite and other poisons to test protective clothing. They were told to keep quiet about the tests, to accept the nausea and burns to their skin, eyes or throat. In return, they were offered extended furloughs and the promise that their scars would heal, that the pain was temporary.

Patriots to the bone, the men of 1st Chemical had respected their oaths, even as their bodies began to falter and their suspicions rose about the chambers they once had entered so willingly. One study showed that a majority of servicemen sworn to secrecy kept their pledge even 50 years later, still believing they’d be sent to Leavenworth if they talked.

But now with the secret finally, wonderfully, cathartically, out, it was time to rethink old assumptions. Did years of sun cause their skin cancer, as they always had believed? Did cigarettes cause their emphysema? Was it their two months at Edgewood or a lifetime of lab work that made them sniffle and hack all winter?

Entering a gas chamber with their buddies seemed like such a small sacrifice when they were recruits. A half-century later, the experiments began to take on a more menacing cast.

“Someone once asked him why he did it,” Elsie Weaver said of her husband, William, who suspected he had health problems linked to the testing and died in 1988. “He said, ‘Well, I was 18. When you’re 18, you don’t think you’ll be dying of anything the government is going to give you.’ “

It is difficult to say how many of the 100 soldiers from the 1st Chemical unit were still alive when the government finally owned up to the experiments in 1991. Many had died obscurely years earlier, their lives – and deaths – a mystery to a government that now vowed to find them.

But that was in the past. Whatever Washington’s mistakes, it now professed a commitment to locate chemical test veterans, wherever they lived.

“The years of silent suffering have ended for these WWII veterans who participated in secret testing during their military service,” Anthony Principi, then-acting-secretary of Veterans Affairs, declared in 1993.

“Be assured,” echoed President Bill Clinton, “this will not be treated as business as usual.”

It was time to take care of these men.

Up stepped Alfred Strauss.

No appeal, no benefits

In June 1993, at age 80, Strauss wrote to the VA from his Century Village apartment in Deerfield Beach, Fla.

The retired chemist’s medical records showed he suffered from several ailments linked to World War II testing: emphysema, chronic coughing and congestion, chronic obstructive lung disease and bronchitis. He just could not seem to catch his breath.

The VA sent Strauss to be examined by Ft. Lauderdale doctor Edward Michaelson.

In a Nov. 12, 1993, report, the doctor pinned Strauss’ ailments on his weight – he was 5 feet 9½, 202 pounds – and a prior smoking habit. Inaccurately noting that Strauss had no history of bronchitis or emphysema, the doctor wrote, “It does not appear as if any exposure to inhaled irritant chemicals or fumes have contributed to his mild to moderate respiratory problem.”

Perhaps the doctor was right. It was difficult to say, 50 years later, whether chemicals or nicotine caused Strauss’ breathing problems. But the VA’s stated policy was to resolve such conflicts in favor of the veteran. The VA had relaxed its requirements for granting mustard gas claims because the military’s own policies – the decades of secrecy, the reluctance to include chemical records in personnel files – made it more difficult for veterans to prove their claims. The VA nonetheless rejected Strauss’ claim, relying on the doctor’s report. Reached recently at his Florida office, Michaelson said federal privacy law prevents him from discussing individual patients. He said, however, that linking a patient’s lung disease to past chemical exposure is a complex task, requiring doctors to consider all aspects of a patient’s history as well as the chemical involved.

“Just because someone was exposed to something doesn’t mean they suffered any permanent impairment related to that exposure,” he said. “The answer you’re looking for is not a simple answer.”

VA officials declined to comment on the specifics of Strauss’ claim.

But Principi – who was not at the VA when Strauss’ claim was rejected – told the Detroit Free Press last month such cases are troubling, if true.

If the chemical-test veterans are being forced to prove their ailments were caused by the experiments, VA officials “are not applying the presumption correctly,” Principi said. “If it’s clear from the medical evaluation that you have a certain disease and there is clear, concrete evidence that you were exposed to mustard gas during some period of time, then you’re deserving of compensation. I mean it’s as simple to me as that.”

Alfred Strauss did not appeal, and he never heard from the VA again. He died in 1999. “He got zero compensation,” said Nellie Strauss, his 92-year-old widow.

Discouraged and dying

Why did the men of 1st Chemical give up? Why would soldiers, some of whom risked their lives overseas, surrender so meekly to a rejection letter?

A few said they felt guilty seeking benefits for injuries suffered outside of combat. Others were dispirited from past VA skirmishes. Indeed, the files of several 1st Chemical soldiers show how they were forced to haggle with the VA for even minor benefits immediately after the war. Others received stern letters ordering them to return “overpayments” of as little as $17 in pay after their discharge.

John L. Hannon, a 1st Chemical volunteer from Delaware, was repeatedly denied benefits after the war for injuries common among chemical test veterans – blurred vision, conjunctivitis, congestion, breathing problems and anxiety.

In 1999, Hannon again sought benefits, this time for anxiety, nose and eye problems. In denying his claim in 2000, the VA wrote, “(T)he evidence does not show full body exposure to mustard gas during active military service.”

In fact, Hannon’s file meticulously records his exposure.

“This man volunteered and participated in tests conducted by the Medical Division,” states an Edgewood record in his VA file. Hannon suffered “2 plus erythema (blisters) on hands” after being “exposed to H (mustard) vapor in the chamber.” The chemicals’ toxicity produced “slight systemic effects.”

Hannon, too, declined to appeal.

As the 1990s rolled on, illness and death took a firmer hold on the men of 1st Chemical.

That is not unexpected in men reaching their 80s. But it was the way they were faltering – from cancers, skin and respiratory diseases – that raised questions about the legacy of Edgewood.

1994: John Hogan, a physician in Utah, went to his grave believing the chronic pain on his leg could be traced to a frayed Army uniform that allowed chemicals to burn his skin. “It would flare up and be burning and red and itchy; he just knew it was from the mustard gas,” said his wife, Valera. “He’d say, ‘If that thing didn’t have holes in it, I’d have been all right.’ “

1995: John Berzellini, an asthmatic locked in a chamber for hours as his mask filled with mucus and drool, died of heart failure in Maryland. The skin on his hands was as delicate as crepe paper. And every winter he was bedridden for weeks with what his wife Irene called “a bronchial thing.”

1997: Francis Earnshaw, the West Virginia recruit sent home for “nerves” only to have his disability claim rejected, died in Ohio. Mary Jo, his wife of 50 years, did not learn the details of his Edgewood training until recently, when contacted by a reporter. “He was a guinea pig,” she declared.

1998: Paul Walters, a Missouri jeweler, died of leukemia, without ever telling doctors about Edgewood’s chambers.

1999: Zenon Siepkowski died after a battle with leukemia and respiratory disease.

Five veterans. Five deaths. None sought benefits for the illnesses that tormented them.

On the road to nowhere

But as the men of 1st Chemical faded, a small team of Pentagon workers was aggressively attacking its mission, combing through archives and remote warehouses – three, four or five times – to find the names of soldiers, sailors or other Americans exposed to chemicals.

The obstacles were daunting. Many Army and Navy chemical rosters had long since vanished, or contained only last names. More critically, millions of World War II Army files perished in a 1973 fire at a St. Louis records center, leaving Pentagon sleuths to search elsewhere.

Martha Hamed, a Pentagon supervisor assigned to the project, recalls spending winter days in the mid-1990s shivering in an unheated Utah warehouse, dragging boxes of veterans’ records to a sunny spot on the floor to keep warm.

Col. Fred Kolbrener, a now-retired project leader, said, “We literally went down a shelf – ‘You’ve got this shelf, I’ve got that one.’ – and we just read everything on that shelf. If we found anything at all that might have names in it, we grabbed it.”

Pentagon workers sometimes called veterans directly to ensure they had the right man. “A lot of us were personally invested in it,” said Hamed, whose father fought in World War II. Veterans “would call the office and say, ‘I’m dying, can you help me?’ It was heartbreaking. So we were on a mission. We tried to leave no stone unturned.”

From 1994 through 1997, the Pentagon compiled roughly 6,500 names – forwarding lists to the VA as they were gathered. “A couple times a month we’d be dropping stuff off at their offices,” Kolbrener said. The Pentagon even sent new commendations to some 772 chemical volunteers.

Officials at the Institute of Medicine, the scientific body that helped analyze the World War II program in 1993, said in an Aug. 2, 1995, internal memo: “Once the DOD decides to investigate fully, the amount they can accomplish is amazing.”

“Unfortunately,” the memo added, “Col. Kolbrener has reported that the VA has not responded very quickly once it is proven that a given individual was, in fact, exposed.”

Indeed, while the Pentagon searched for veterans’ names into 1997, the VA had quietly stopped tracking mustard gas claims three years earlier, when media and congressional attention began to wane.

The Free Press discovered the VA failed to directly notify any veterans or chemical workers of the health risks posed by the tests or their eligibility for benefits. No letters, no phone calls. The agency did not even run Pentagon lists through Internal Revenue Service computers or other government agencies to find current addresses for the chemical veterans, as it had promised Congress.

Even today, the VA cannot produce records on chemical claims after 1994. What records they have show the agency processed slightly more than 2,000 claims by September 1994, granting benefits to 193 people – fewer than 10 percent.

Who filed claims? Some were guinea pigs at places like Edgewood. Others helped make or transport chemical weapons for the military. Still others were ordinary enlisted men who may have mistaken the routine training exercises of their war years for true chemical tests.

Different people. Different circumstances. One common trait: They approached the VA. The VA didn’t go to them.

And the men of 1st Chemical? They are still not officially acknowledged. The government database on the test program does not list the unit among those that participated in chemical experiments.

No answers from VA

Kolbrener, now a security analyst with Virginia-based Xacta Corp., said last week he had no idea the VA had not searched for the people identified by his team. “I would think that that’s why we were doing it,” Kolbrener said.

The VA officials who testified to Congress in 1993 cannot, or will not, explain now what went wrong.

Vogel, who left the VA, refused comment. He referred questions to Quentin Kinderman, his assistant policy director. Now retired, Kinderman said, “I’m not sure I can really answer that. It really surprises me we would have dropped the issue at that time without doing something.”

Those answers stunned Jim Slattery, the Kansas congressman who chaired the 1993 hearing.

“When government officials from the executive branch come before a committee in Congress and make a commitment, that’s a sacred commitment and it must be honored,” said Slattery, now a Washington attorney. “It’s very disappointing.”

Principi, the VA secretary, said he was unaware of any problems with the chemical program until the Free Press raised questions about it in the summer. He noted he left the agency in January 1993, when Clinton took office, and did not return until 2000.

“Quite honestly, you hate to learn about these things from others, that veterans have not been receiving their benefits,” Principi said. “But the important thing to me is when a problem has been identified, to try to fix it, to try to help people. They served their nation honorably” so the VA must “do what we can to provide health care and compensation to them. That’s always been my bottom line and still is my bottom line. … If more needs to be done, it will be done.”

VA researchers sought out 500 mustard-gas veterans, eventually interviewing 363 by phone. To make the veterans feel comfortable answering questions, the researchers promised they would not share their conversations with other VA offices.

Dr. Paula Schnurr, deputy director of the VA’s post-traumatic stress research center, said the study cost $230,000. VA officials concede they could have used the same methods to search for the roughly 4,000 men used in chamber and field tests during the war. Assuming half of those men were alive in 1996, it would have cost the VA less than $1 million to find them and gauge their eligibility for benefits.

Principi, a combat-decorated Vietnam veteran, said last month it was not too late to act.

“If the VA promised to do a direct mailing and we did not do a direct mailing, having had their location and their addresses, then I would say we did let them down,” he said. “If we did not, if my successor did not, whomever, me or anybody else, then I say we need to go back and take another look and see what should be done.”

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy