Identifying the enemy can be difficult; mistakes can be costly, in lives, allegiances.

Identifying the enemy can be difficult; mistakes can be costly, in lives, allegiances.

by Andrew Maykuth

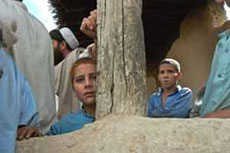

Left: A boy peers from behind a house post in the Afghan village of Bar Shultan, near the border with Pakistan. His father and brother were among eight people killed last month when a U.S. team conducted a raid at the house. The U.S. military says the raid targeted terrorists. The villagers say only civilians were killed.

BAR SHULTAN, Afghanistan–When the gunfire started about 2 a.m. outside the mud-walled compound, Malik Namatullah woke abruptly: The commandos had already scaled the wall and peered over the top.

The soldiers wore camouflage uniforms, night-vision scopes, and black balaclavas concealing all but their eyes. Their rifles were trained on Namatullah.

“It’s the Americans,” the farmer told his startled friends in this mountainous village along the Kunar River, six miles from the Pakistan border. “Don’t move.”

Namatullah’s strategy no doubt saved his life early that morning Aug. 24. Others were not so fortunate. A U.S. Special Forces team killed eight people at the house during the lightning strike, including a 12-year-old boy…

A coalition spokesman says the raid targeted terrorists. The villagers say only civilians were killed. Their fate illustrates the treacherous path the war has taken here after five years, where the allegiance of townspeople will ultimately determine the outcome, but where every civilian death is a propaganda victory for Islamic radicals.

According to the coalition, the U.S. forces were fired upon during an attempt to detain a man who they said collaborated with Arab extremists. The dead included the “al-Qaeda facilitator,” Alam Zair, the owner of the house, who was about 40.

But Namatullah and local officials insist Alam Zair was no terrorist. They say the Americans killed five elders from the ethnic Pashtun village who happened to be staying overnight to resolve a land dispute. Namatullah was among the visiting elders.

Within 24 hours, the Americans found themselves engulfed in a political crisis. Parliament expressed outrage at the American aggressiveness. President Hamid Karzai, under pressure from Afghans upset by the foreign military forces, promised an investigation.

U.S. forces quickly released four men they had detained during the raid, including Namatullah. The Afghan government pledged cash reparations to families of the dead. But the public damage was done.

“Unfortunately, this is not an unusual case,” said Shahzada Shahid, a Muslim cleric and a member of parliament from the area. “Gradually the opinions of people are turning against the Americans.”

In the three weeks since the attack, a clearer picture has emerged between the two seemingly incompatible accounts of events Aug. 24.

“Something happened that wasn’t intended,” acknowledged U.S. Navy Cmdr. Ryan B. Scholl, the head of the provincial reconstruction team in Kunar province, who has visited local officials after the incident and promised U.S. assistance to Bar Shultan.

While the Americans quietly expressed regret for the loss of life, Karzai’s office also muted its protests after being shown U.S. intelligence on the intended target. There is “some truth” to the Americans’ claim that Alam Zair was an enemy operative, said Jawad Ludin, Karzai’s chief of staff.

Bar Shultan is in a murky, stateless world, literally on the edge of Afghanistan, where tribal residents have traditionally been given autonomy. “We were free people, not under the control of Afghanistan or Pakistan,” said Anwar Khan, a white-bearded resident. Only in recent years under Karzai’s government have residents been treated as Afghans and given government identity cards.

Vehicles can reach the village only on a dirt road that the local people say is unsafe. So most people enter Bar Shultan by crossing the Kunar River in a raft lashed together from inner tubes and planks, propelled by four oarsmen who frantically fight the swift current.

For generations, Afghans have smuggled goods and arms through the steep, scrub-covered canyons that connect the river to the towering ridgeline marking the border with Pakistan. During the jihad against the 1980s Soviet occupation, mujaheddin infiltrated Afghanistan from Pakistan across these routes. Osama bin Laden was said to have operated here. Today the Taliban uses the same routes.

With no long-term relationship to a central government, residents typically resolve disputes through tribal councils, or shuras, made up of elders. When talk fails, they settle disputes with guns. So it was no surprise to locals that when the Americans came, they encountered plenty of firearms.

“Yes, of course, the Americans found guns and weapons,” said Saleh Muhammad, the Shigal District police chief, who guided two American visitors to the village on Sept. 2. “They’re Afghans. They have private problems between each other. Everybody has guns.”

The day before the attack, the chief of Shigal District called the village elders to his office for a daylong shura to help resolve a dispute over a 150-foot-long farm plot claimed by Alam Zair and a neighbor. As is the Pashtun custom, Alam Zair invited the elders to dinner and at the end of the day provided them with a place to sleep before they returned to their homes in the hills the next morning, Muhammad said.

It was a warm night, so five of the elders dragged their wood-framed beds and thin mattresses outside the mud walls to sleep in a breeze, Namatullah said. They were the first men the commandos encountered when they approached Alam Zair’s compound in the night.

Col. Tom Collins, a coalition spokesman, said the Afghans, who he said were guarding Alam Zair’s house, ignored a call to drop their guns, so American forces fired on them.

Scholl, the local American commander, said he believed the men outside the house were simply elders who picked the wrong night to stay at Alam Zair’s house. “We don’t have any information that they were bad elements,” he said.

“That side of the river doesn’t see too many coalition soldiers,” Scholl said. Surprised at night, he said, the elders probably reacted in a way “that got them killed.”

Neighbors who recovered the bodies said the fight was one-sided. They found four of the five men outside lying in their beds, shot in the head. Muhammad said that most of the bullet casings left on the ground were from American guns, not Kalashnikovs, which the local people favor. And the remarkably few bullet holes in the mud walls indicated an abbreviated firefight.

Alam Zair was killed near the front entrance to his house. The commandos who had climbed the mud walls fired into the kitchen, killing his son, Rauf, and critically wounding one of his wives. (She was flown to an American military hospital with no male family member accompanying her, prompting rumors that the Americans had kidnapped her.)

The eighth victim was Alam Zair’s older brother, Abdul Karem, who was gunned down after he came running from his house a few hundred yards away, carrying a lamp and a Kalashnikov.

A coalition spokesman said an American helicopter firing rockets also scattered unknown al-Qaeda elements surrounding the house. Villagers contended they were not al-Qaeda members but neighbors coming to see what the fuss was about.

The villagers denied that Alam Zair was helping the extremists and that the Americans must have acted on bad intelligence from somebody who was Zair’s enemy. But the coalition says it has multiple intelligence sources that show he was helping Arab extremists infiltrate from Pakistan into eastern Afghanistan. Local officials do acknowledge that Zair was associated with Afghan warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, a radical Islamist who has sided with al-Qaeda against the Americans. Hekmatyar still has a large following in Kunar.

When asked about al-Qaeda, villagers shrug and point at the mountains, where insurgents recently fired at an American-funded construction crew that is rebuilding the primary road that runs up the Kunar valley.

“They’re shooting rockets from up there,” said Anwar Khan. “They’re Pakistanis, not Taliban. They’re trying to stop the reconstruction of the country. They’re telling us not to participate in the reconstruction of our country.”

Scholl said the Americans would compensate the families of the tribal elders for the loss of their breadwinners. A State Department team will also look at bringing in a development project to Bar Shultan.

Local political leaders say that in the Pashtun culture, the offers of reparations go a long way to resolving hard feelings. Still, they said, the killings were senseless.

“There was no need for it,” said Shalizai Didar, the Kunar governor. “Alam Zair wasn’t the type of guy to run away. He had family living there. We could have brought him in for questioning if they had asked.”

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully Informed

In fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy