Veterans conquer new goals with support of fellow wounded, the military and the public

Veterans conquer new goals with support of fellow wounded, the military and the public

by E.A. Torriero, Chicago Tribune

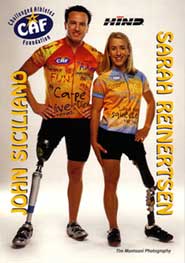

Left, John Siciliano and Sarah Reinertsen devote personal time and energy toward helping other amputees through The Challenged Athletes Foundation.

These days, Kelly, 25, is a helicopter pilot instructor in Arizona realizing a boyhood dream by flying above the mountains with students hard-pressed to notice his disability. He flies not over Baghdad, Iraq, but Bagdad, Ariz.

“I didn’t want to be a liability to someone else,” Kelly said. “I decided I couldn’t climb ladders well enough to rescue someone as a firefighter. But that doesn’t mean I can’t do something else that I’ve always wanted to do.”

In a toll not seen since the Vietnam War, Kelly is one of more than 550 war amputees in various stages of adjusting to life back in America. And unlike many of those who returned from Vietnam, they are getting a warm welcome home and can get help from support groups.

Like Tammy Duckworth, who made a spirited bid for Congress in suburban Chicago, and triple amputee Army Staff Sgt. Bryan Anderson, who returned home this week to Rolling Meadows, the amputees are notably visible.

On the ski slopes. Surfing the ocean waves. In corporate offices. On college campuses. As business owners. And in politics. War amputees are woven into the American fabric not only as symbols of the price of war but also of perseverance…

“We are living reminders of the sacrifice this country has made in Iraq,” said Ed Pulido, who lost his left leg after being wounded in Iraq in 2004. “You learn to adapt, to walk with God and live day by day.”

Pulido is one of many amputees helping to counsel newly returning wounded from Iraq as part of the non-profit Wounded Warrior Project.

“Ultimately you either lie in bed and grieve or get up and succeed,” said Pulido, an executive with the United Way of Central Oklahoma, a job he held before being called up from the Reserves for active duty.

As the war churns on, the Pentagon is geared to receive many more amputees. In a sign of recognition of the growing number of amputees, a $1 million federal grant has been awarded to university researchers in Ohio and Indiana. The researchers are about to begin an unprecedented survey of some of the more than 5,000 Vietnam-era amputees to figure out how to better serve those injured in Iraq.

“We hope to use their experiences from the past to predict the needs of Iraq war wounded,” said Chris Robbins, one of the researchers at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

Unlike after the Vietnam War, today’s wounded soldiers not only are finding a less frosty reception back in the U.S., they also are receiving state-of-the-art medical care and support from volunteer organizations designed to assist them.

“The general political climate is different,” said Kirk Bauer, who lost a leg in the Vietnam War and is executive director of Disabled Sports USA, which provides recreational outings for amputees.

“While there is opposition to the war, it’s not about taking it out on the soldiers,” he said. “When someone comes back without an arm or a leg, they are finding nothing but support. The acceptance makes it so much easier to move on.”

Iraq wounded nears 12,000

Nearly 12,000 Americans have returned from Iraq with injuries, from physical to psychological.

Those who have lost limbs enter specialized units at two military hospitals outside Washington, D.C., and in Texas where they are fitted with artificial devices, often in less than a month. They battle infections and bouts of depression.

Volunteer and non-profit support groups such as Wounded Warriors offer a buddy system in which former amputee patients spend hours at a time with those who are recovering.

“To be with someone who has gone through it before is invaluable,” said Richard “RJ” Meade, a counselor with the Wounded Warrior Project at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

In interviews, Iraq amputees and their counselors say one of the most trying times comes when amputees return home after a long rehabilitation.

Though many succeed, some don’t, they say. Some amputees become mired in sadness, abuse drugs and alcohol, and isolate themselves.

Erick Castro, 24, lost his left leg at the hip during an attack on the armored personnel carrier he was riding in on Aug. 25, 2003, outside Fallujah.

Less than a year later, he was back in California and spent the summer as a virtual shut-in. He was having trouble with his artificial legs, couldn’t bring himself to travel beyond his front door and was just lying in bed playing video games.

With the help of his girlfriend, who later became his wife, Castro said, he eventually summoned the courage to venture out. Today he is a proud father and a student at Arizona State University studying mechanical engineering. He hopes to someday develop devices for wounded veterans.

“Everyone hits a point where it’s like you can’t go on,” he said. “But you’ve got to push yourself. Once you get past it, you find that there is a life out there.”

Firefighting in the future?

A few hours north of Phoenix, former Staff Sgt. Kelly has learned that life’s detours can open new doors.

During his recovery at Walter Reed, Kelly played a key role in advocating better benefits for the wounded. Congress passed a bill providing added military insurance payouts for limb losses for a premium of just an extra $1 per month.

And while at Reed, Kelly learned that a childhood dream still was in reach. Nearsightedness had precluded him from becoming a pilot in the military. But he found out that civilian pilot requirements are not as stringent.

He enrolled at a high-altitude flight school in Prescott, Ariz., where the school’s owner was unfazed by his disability because his father made a living creating prosthetic devices.

Now as Kelly flies high, he hopes to double back on a once-abandoned goal of fighting fires–but with a copter.

“The only difference is that I’ll be fighting them from the air and not the ground,” he said.

– – –

Amputees’ long road

In Iraq, the wounded are rushed to surgery, stabilized and then flown hours later to a medical center in Germany.

Within days they arrive stateside at two Army hospitals designed to treat amputees. Artificial limbs are fitted within a month and eight to 14 months of rehabilitation begins; infections usually set back recovery.

Amputees rejoin civilian life, often attending college classes on veterans’ benefits. Two to four years later, they integrate into the working world.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully Informed

In fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy