Vet Who Contracted Infectious Disease While Deployed, Transmits Disease to Wife and Unborn Children

Vet Who Contracted Infectious Disease While Deployed, Transmits Disease to Wife and Unborn Children

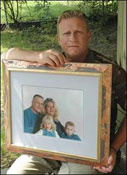

Left, Arvid Brown holds a 1999 family portrait. His wife, Janyce, died last year, and children Asa and Helen are disabled. Brown links their health woes to a disease he contracted in the Mideast.

This is a rather tragic case of a Gulf War veteran who contracted an infectious disease while deployed and later transmitted the disease to his wife who in turn transmitted it to their child in utero. The wife has since died.

VA initially sought governmental immunity under the Feres Doctrine but, in an appeal by attorney Robert Walsh to the 6th Circuit, this was found to not be applicable in a claim against VA.

Now a federal judge has denied the government’s efforts to have the lawsuit terminated as a matter of law ruling that our case can proceed on the theory that VA doctors owe family members a duty to warn them of potential risks when the veteran has symptoms of an infectious disease. Army veteran Arvid Brown, while serving in Saudi Arabia during the Persian Gulf War in 1991, was bitten by "sand flies" and contracted the parasitic disease Leishmaniasis. Sand fly bites are the most common vector by which this infectious disease is transmitted to humans…

Upon discharge from active duty, Mr. Brown of Flint was treated at Michigan VA hospitals for service related symptoms on over 50 visits. The VA never looked for Leishmaniasis as a cause of his symptoms, ignoring his service and medical history. Mr. Brown was finally diagnosed by a private physician in Michigan with Leishmaniasis in 1998. Mr. Brown’s wife was infected with Leishmaniasis because no one ever diagnosed Mr. Brown and told him of the infectious nature of this disease and its ability to be transmitted by sexual activity. Mrs. Brown gave birth to two children – both of whom were infected with Leishmaniasis in the womb.

His wife and children sued the VA under the Federal Torts Claim Act in September 2004 because they were infected with Leishmaniasis. The Government sought to have the case dismissed claiming that the VA owed no duty to the Veteran’s family. The family claimed that VA doctors committed malpractice in not diagnosing Leishmaniasis and failing to warn the wife that the disease could be transmitted to her and the children.

Judge John Corbett O’Meara of the United States District Court, Eastern District of Michigan, denied the Government’s Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings which claimed that the Government owed no duty to the family of a Veteran in an Order dated June 18, 2007.

The Court, relying on Michigan law, concluded that VA doctors do owe family members a duty to warn of risk when patients present with symptoms of a disease that is well known to be contagious. A duty of reasonable care may arise on the part of the Government.

The case against the VA will continue and the parties have agreed to try the issues of liability in the fall of 2007.

Contact information: Thomas F. Campbell (313-410-0017 /mobile)

Michael Viterna

Fausone Bohn, LLP

www.fb-firm.com

Northville, Michigan

(248) 380-0000

www.legalhelpforveterans.com.

Is family a Gulf War casualty? Ruling lets ill widower propel lawsuit

by Paul Egan / The Detroit News

SWARTZ CREEK — Nobody can say U.S. Army veteran Arvid Brown’s Gulf War illness is all in his head.

Brown’s late wife, Janyce, caught leishmaniasis — a sometimes deadly parasitic disease borne by sand flies that can attack the body’s cells and internal organs — a malady he brought home from Operation Desert Storm. So did the Swartz Creek couple’s two young children.

Now, the U.S. Court of Appeals has ruled the federal government and the Department of Veterans Affairs can be sued for alleged failure to diagnose Brown’s illness and for any injuries he and his family suffered.

Veterans’ groups are hailing the decision as a victory for families of tens of thousands of veterans of not only the first Gulf War, in which Brown served, but subsequent Mideast conflicts.

"This is a huge case," said Joyce Riley, spokeswoman for the American Gulf War Veterans Association in Versailles, Mo. "This gives a lot of veterans a lot of hope."

When Brown, now 48, returned from the Gulf War in 1991, he couldn’t understand why his once-vigorous health was deteriorating. His head, muscles and bones ached, his strength was sapped; he was constantly exhausted but could not sleep.

Doctors with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs could not pinpoint an ailment. They denied him disability benefits in 1995, and Brown said they prescribed painkillers and mood-altering drugs that made things worse.

It was Brown’s wife, Janyce, who had the research skills and persistence eventually to find a doctor who in 1998 diagnosed Brown with leishmaniasis.

By then, Janyce, too, had contracted the disease and both the couple’s children had been born with it and other ailments, according to medical reports filed in the case from Dr. Gregory Forstall, then-director of infectious diseases at McLaren Regional Medical Center in Flint, now in private practice.

The government has not disputed the medical reports.

Janyce Brown developed a series of ailments and last year died at age 43 of a rare and inoperable form of liver cancer. Though no definite link was established between her leishmaniasis and other diseases, Arvid Brown said his wife was healthy before they met.

Janyce Brown in 2004 brought a $125 million lawsuit against the government, but a federal judge in Detroit ruled the family couldn’t sue for injuries a soldier suffered while on active duty.

U.S. District Judge John Corbett O’Meara’s decision was based on the Feres doctrine, after the soldier involved in a precedent-setting 1950 U.S. Supreme Court decision. Army Lt. Rudolph J. Feres died in a 1947 fire caused by a defective heater in a military barracks at Pine Camp, N.Y. The court ruled his widow could not sue because Feres was on active duty.

Late last month, the U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati partially overturned O’Meara’s decision, saying the government is not liable for injuries suffered while Brown was on active duty but it can be sued for what happened once he returned to Michigan. The government may appeal, officials said.

"They should not be allowed to just use us up and throw us away," said Brown, now alone and raising two disabled children, ages 9 and 10, on his disability income. "Somebody has got to be accountable."

Many look toward lawsuit

Mark Zeller, 42, a Gulf War veteran in Dahlonega, Ga., said he is about to bring a lawsuit against the government and believes the decision in Brown’s case will strengthen his legal position.

"I can’t do anything and I have to sleep all the time," said Zeller, who has been diagnosed by Veterans Affairs doctors with chronic fatigue syndrome but says his wife and five children also constantly suffer from flulike symptoms.

The Feres doctrine "safeguards the government, but what safeguard do we have?" asked Zeller.

Leishmaniasis is little-known in North America but common in southwest Asia and many other parts of the world. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 12 million people in the tropics and subtropics have the disease. One form produces skin lesions. The more severe and deadly form, which Brown has, attacks blood cells and the body’s internal organs. Like malaria, it is a chronic disease that can be controlled but not cured.

Dr. Katherine Murray Leisure is a former Department of Veterans Affairs doctor now in private practice in Lebanon, Pa., specializing in infectious diseases. She said leishmaniasis if often difficult to diagnose and could be an underlying factor in half or more of the thousands of cases of veterans commonly referred to as suffering from "Gulf War syndrome."

Bedouins and others who live in the desert clothe their entire bodies for good reasons, Murray Leisure said. But, when U.S. forces go to the desert to fight, "we try to pretend we’re at the Jersey shore."

Situation likened to Titanic

Terry Jemison, a spokesman for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, said he could not comment on the Brown case because of the ongoing court case. But he said the department is aggressively researching the ailments of Gulf War veterans and plans to spend $15 million a year on research for the next five years.

No reliable numbers are available on how many family members believe they have been infected. But Riley, a registered nurse and former U.S. Air Force captain, said she believes tens of thousands of veterans’ relatives have suffered.

"I think this is the Titanic," said Robert P. Walsh, Brown’s Battle Creek attorney. "All these guys saw was the tip of the iceberg."

Arvid Brown, who grew up in southwest Detroit, spent about six months overseas during Desert Storm, helping to build, maintain and operate a prisoner of war camp near Hafr Al-Batin in northeastern Saudi Arabia, about 25 miles from the Iraqi border.

Brown remembers the sand flies, the camel spiders and the bug repellent. He remembers meeting soldiers in the desert who wore dogs’ flea collars around their necks, wrists and ankles and thinking how unhealthy that seemed.

The muscle aches, bone pains, headaches and rashes began while he was in Saudi Arabia, but "it was easy to attribute it to heat and everything I was doing," Brown recalled.

Long-delayed diagnosis

Solving the mystery would take seven years as Brown’s condition worsened through periods of disorientation, blackouts, extreme light sensitivity and almost unbearable pain. By 1998, when he was finally diagnosed, Brown had lost his job, been forced to give up driving and said he awoke early most mornings from a fitful sleep, vomiting blood.

Veterans Affairs doctors, who according to court records examined Brown on Sept. 13, 1994, but did not detect the disease, said he was suffering anxiety attacks and prescribed pills, Brown said. The department did not grant him benefits until 1998 and only this year recognized his diagnosis of leishmaniasis.

Jemison, the VA spokesman, said the department "remains committed to ensuring all veterans receive high-quality care."

In its answer to the lawsuit, the VA denied failing to diagnose Brown and denied committing malpractice in the medical care it gave Brown.

Somehow, amid the pain and fatigue, Brown, who was divorced from his first wife soon after returning from the Gulf, was able to meet and marry the woman he credits with saving his life.

Brown wed Janyce Surface in September 1994 as his health continued to spiral downward. He lost his job and they struggled to pay bills. Children arrived: Asa, now 10, in 1995, and his sister, Helen, now 9, in 1997. Both were born with severe handicaps and later tested positive for leishmaniasis. Helen is still unable to speak.

It was Janyce Brown who got her husband an appointment with Forstall, who diagnosed Arvid Brown with leishmaniasis in October 1998. Chemotherapy put the disease into remission, though Brown continues to struggle with his health today.

By 2000, Janyce Brown and both children had also tested positive for leishmaniasis. As Janyce struggled to care for her husband and look after two young children with cerebral palsy, her own health rapidly deteriorated. She died at home of cancer.

"She was an extremely intelligent individual, someone with the will and the nerves of steel and the tenaciousness of the meanest bulldog you had ever come across," Brown said.

"She was fighting for her husband, the man she loved … and her children … She will always be my biggest hero."

You can reach Paul Egan at (313) 222-2069 or pegan@detnews.com.

More information about Leishmaniasis

What is Leishmaniasis?

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by protozoan parasites that belong to the genus Leishmania and is transmitted by the bite of certain species of sand fly, including flies in the genus Lutzomyia in the New World and Phlebotomus in the Old World. The disease was named in 1901 for the Scottish pathologist William Boog Leishman. This disease is also known as Leichmaniosis, Leishmaniose, leishmaniose, and formerly, Orient Boils, kala azar, black fever, sandfly disease, Dum-Dum fever or espundia.

Most forms of the disease are transmissible only from animals (zoonosis), but some can be spread between humans. Human infection is caused by about 21 of 30 species that infect mammals. These include the L. donovani complex with three species (L. donovani, L. infantum, and L. chagasi); the L. mexicana complex with 3 main species (L. mexicana, L. amazonensis, and L. venezuelensis); L. tropica; L. major; L. aethiopica; and the subgenus Viannia with four main species (L. (V.) braziliensis, L. (V.) guyanensis, L. (V.) panamensis, and L. (V.) peruviana). The different species are morphologically indistinguishable, but they can be differentiated by isoenzyme analysis, DNA sequence analysis, or monoclonal antibodies.

Visceral leishmaniasis is a severe form in which the parasites have migrated to the vital organs.

Geography and epidemiology–It effects Veterans

Leishmaniasis can be transmitted in many tropical and sub-tropical countries, and is found in parts of about 88 countries. Approximately 350 million people live in these areas. The settings in which leishmaniasis is found range from rainforests in Central and South America to deserts in West Asia. More than 90 percent of the world’s cases of visceral leishmaniasis are in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil.

Leishmaniasis is also found in Mexico, Central America, and South America—from northern Argentina to southern Texas (not in Uruguay, Chile, or Canada), southern Europe (leishmaniasis is not common in travelers to southern Europe), Asia (not Southeast Asia), the Middle East, and Africa (particularly East and North Africa, with some cases elsewhere). The disease is not found in Australia or Oceania.

Leishmaniasis is present in Iraq and was contracted by a number of the troops involved in the 2003 invasion of that country and the subsequent occupation. The soldiers nicknamed the disease the Baghdad boil. It has been reported by Agence France-Presse that more than 650 U.S. soldiers may have experienced the disease between the start of the invasion in March 2003 and late 2004. [1] [2]

In fact, U.S. troops have experienced leishmaniasis cases in the Middle East already previously to the 2003 invasion, during the time of the previous Gulf conflict, when a large number of soldiers were stationed in Saudi Arabia. Of the 32 cases that were recorded by the U.S. military for that period (1990-1991), 20 were cutaneous, and 12 of the more severe visceral type [www.pdhealth.mil/downloads/Leishmaniasis_exsu_16Mar042.pdf].

During 2004, it is calculated that some 3,400 troops from the Colombian army, operating in the jungles near the south of the country (in particular around the Meta and Guaviare departments), were infected with Leishmaniasis. Apparently, a contributing factor was that many of the affected soldiers did not use the officially provided insect repellent, because of its allegedly disturbing odor. It is estimated that nearly 13,000 cases of the disease were recorded in all of Colombia throughout 2004, and about 360 new instances of the disease among soldiers had been reported in February 2005. [3] [4] [5]

In September 2005 the disease was contracted by at least four Dutch marines who were stationed in Mazari Sharif, Afghanistan, and subsequently repatriated for treatment.

Within Afghanistan, in particular Kabul is a town where leishmaniasis occurs commonly – partly to do with bad sanitation and waste left uncollected in streets, allowing parasite-spreading sand flies an environment they find favorable. See e.g. [6] and [7]. In Kabul the number of people infected is estimated at at least 200,000, and in three other towns (Herat, Kandahar and Mazar-i-Sharif) there may be about 70,000 more, according to WHO figures from 2002 cited e.g. here: [8].

Life cycle

Life cycle of the Leishmaniasis parasite. Source: CDCLeishmaniasis is transmitted by the bite of female phlebotomine sandflies. The sandflies inject the infective stage, metacyclic promastigotes, during blood meals (1). Metacyclic promastigotes that reach the puncture wound are phagocytized by macrophages (2) and transform into amastigotes (3). Amastigotes multiply in infected cells and affect different tissues, depending in part on which Leishmania species is involved (4). These differing tissue specificities cause the differing clinical manifestations of the various forms of leishmaniasis. Sandflies become infected during blood meals on an infected host when they ingest macrophages infected with amastigotes (5,6). In the sandfly’s midgut, the parasites differentiate into promastigotes (7), which multiply, differentiate into metacyclic promastigotes and migrate to the proboscis (8)

Signs and symptoms of Leishmaniasis

The symptoms of leishmaniasis are skin sores which erupt weeks to months after the person affected is bitten by sand flies. Other consequences, which can become manifest anywhere from a few months to years after infection, include fever, damage to the spleen and liver, and anaemia.

In the medical field, leishmaniasis is one of the famous causes of a markedly enlarged spleen, which may become larger even than the liver. There are four main forms of leishmaniasis:

Visceral leishmaniasis – the most serious form and potentially fatal if untreated.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis – the most common form which causes a sore at the bite site, which heal in a few months to a year, leaving an unpleasant looking scar. This form can progress to any of the other three forms.

Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis – this form produces widespread skin lesions which resemble leprosy and is particularly difficult to treat.

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis – commences with skin ulcers which spread causing tissue damage to (particularly) nose and mouth

Treatment

There are two common therapies containing antimony (known as pentavalent antimonials), meglumine antimoniate (Glucantim®) and sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam®). It is not completely understood how these drugs act against the parasite; they may disrupt its energy production or trypanothione metabolism. Unfortunately, in many parts of the world, the parasite has become resistant to antimony and for visceral or mucocutaneous leishmaniasis,[1] but the level of resistance varies according to species.[2] Amphotericin is now the treatment of choice; failure of AmBisome® to treat visceral leishmaniasis (Leishmania donovani) has been reported in Sudan,[3] but this failure may be related to host factors such as co-infection with HIV or tuberculosis rather than parasite resistance.

Miltefosine (Impavido®), is a new drug for visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis. The cure rate of miltefosine in phase III clinical trials is 95%; Studies in Ethiopia show that is also effective in Africa. In HIV immunosuppressed people who are coinfected with leishmaniasis it has shown that even in resistant cases 2/3 of the people responded to this new treatment. Clinical trials in Colombia showed a high efficacy for cutaneous leishmaniasis. In mucocutaneous cases caused by L.brasiliensis it has shown to be more effective than other drugs. Miltefosine received approval by the Indian regulatory authorities in 2002 and in Germany in 2004. In 2005 it received the first approval for cutaneous leishmaniasis in Colombia. Miltefosine is also currently being investigated as treatment for mucocutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L. braziliensis in Colombia,[1] and preliminary results are very promising. It is now registered in many countries and is the first orally administered breakthrough therapy for visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis.[4](More, et al, 2003). In October 2006 it received orphan drug status from the US Food and Drug administration. The drug is generally better tolerated than other drugs. Main side effects are gastrointetinal disturbance in the 1-2 days of treatment which does not affect the efficacy. Because it is available as an oral formulation, the expense and inconvenience of hospitalisation is avoided, which makes it an attractive alternative.

The Institute for OneWorld Health has developed paromomycin, results with which led to its approval as an orphan drug. The Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative is also actively facilitating the search for novel therapeutics.

Drug-resistant leishmaniasis may respond to immunotherapy (inoculation with parasite antigens plus an adjuvant) which aims to stimulate the body’s own immune system to kill the parasite.[5]

Several potential vaccines are being developed, under pressure from the World Health Organization, but as of 2006 none is available. The team at the Laboratory for Organic Chemistry at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zürich are trying to design a carbohydrate-based vaccine [9]. The genome of the parasite Leishmania major has been sequenced,[6] possibly allowing for identification of proteins that are used by the pathogen but not by humans; these proteins are potential targets for drug treatments.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy