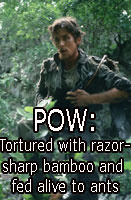

Tortured with razor-sharp bamboo and fed alive to ants: The story behind one PoW's incredible escape from Vietnam

Tortured with razor-sharp bamboo and fed alive to ants: The story behind one PoW's incredible escape from Vietnam

by Zoe Brennan

Flying low over the dangerous and impenetrable Laotian jungle on a bombing mission against the Viet Cong, U.S. Air Force Colonel Eugene Deatrick saw a lone figure waving to him from a clearing below.

He continued on his flight path, but ten minutes later – puzzled that a native in this hostile terrain would try to attract his attention – he decided to turn back for another recce.

This time, he saw the letters SOS spelt out on a rock. Beside them stood an emaciated man dressed in rags, waving the remains of a parachute over his head and signalling desperately.

Deatrick radioed headquarters, who told him that no Americans had been shot down in the area, and instructed him to carry on. But the man continued waving, mouthing over and over again: "Please don't leave." (continued…)

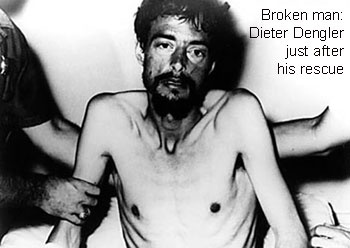

Eventually, at Deatrick's insistence, two rescue helicopters were scrambled. Dropping a cable down to the frantic figure, they winched him on board. Fearful that he could be a Viet Cong suicide bomber, the crew pinned the six stone man to the helicopter deck and searched him – his backpack turned out to contain only a half-eaten snake.

Almost beyond speech, the man whispered: "I am an American pilot. Please take me home."

Contacting control command, the helicopter eventually received verification: they had found Lieutenant Dieter Dengler, the only American ever to break out of a prisoner of war camp in the Laotian jungle and live to tell the tale.

The year was 1966. Dengler had been missing, presumed dead, for six months, and subjected to barbaric torture at the hands of his captors.

But, plotting his getaway in the tiniest detail over several months, he at last escaped his prison by sheer force of will, surviving in the world's fiercest wilderness with primal tenacity as death stalked his every step.

Emerging back into civilisation, he captivated the American nation with his astonishing story and film star looks – a lone ray of hope in the horrors of the Vietnam War.

Now, Dieter Dengler's extraordinary journey has been made into a gripping new film, Rescue Dawn, starring Christian Bale.

They could scarcely have asked for more inspiring source material. For in the annals of history's great escapes, there is no story quite like that of Lieutenant Dengler.

It started in war-time Germany, where Dengler grew up. Huddled with his tiny brother in an attic in the Black Forest region, the young Dengler looked out of the window to see an Allied fighter plane flying just a few hundred feet away.

The cockpit was open, and there sat the pilot, his goggles raised on his forehead, black leather gloves gripping the controls. Dengler was captivated.

As a teenager, he emigrated to America, signed up to join the U.S. Air Force as a pilot and was assigned to an aircraft carrier heading for Vietnam. On the morning of February 1,

1966 – just after becoming engaged to his sweetheart, Marina – Dengler launched from the U.S.S Ranger with three other aircraft on a top-secret bombing mission near the Laotian border.

Visibility was poor, and as Dengler rolled his Skyraider in on the target after flying for two-and-a-half hours into enemy territory, he was strafed by anti-aircraft fire.

"There was a large explosion on my right side," he remembered when interviewed shortly before his death in 2001. "It was like lightning striking. The right wing was gone.

"The airplane seemed to cartwheel through the sky in slow motion. There were more explosions – boom, boom, boom – and I was still able to guide the plane into a clearing."

He said: "Many times, people have asked me if I was afraid. Just before dying, there is no more fear. I felt I was floating."

Thrown 100ft from the plane in a crash-landing, Dengler lay unconscious for a few minutes before running into the jungle to hide.

For two days, he lived on the run in the jungle, strapping his injured left leg with bamboo, before being found by the local Pathet Lao, the Laotian equivalent of the communist Viet Cong.

They took him captive and marched him through the jungle. At night, he was tied spread-eagled on the ground to four stakes to stop him escaping.

In the mornings, his face would be so swollen from mosquito bites he was unable to see.

Far worse was to come. After an early escape attempt, Dengler was picked up by his guards at a jungle water hole. This was when the torture began.

"I had escaped from them, they wanted to get even," he said.

They would hang him upside down by his ankles, with a nest of biting ants over his face, until he lost consciousness. At night, they suspended him in a freezing well so that if sleep came, he feared he would drown.

Other times, he was dragged by water buffalo through villages, his guards laughing as they goaded the animal with a whip.

Bloodied and broken, he was asked by Pathet Lao officials to sign a document condemning America, but still he refused, so the torture intensified. Tiny wedges of bamboo were inserted under his fingernails and into incisions on his body to grow and fester.

Bloodied and broken, he was asked by Pathet Lao officials to sign a document condemning America, but still he refused, so the torture intensified. Tiny wedges of bamboo were inserted under his fingernails and into incisions on his body to grow and fester.

"They were always thinking of something new to do to me," Dengler recalled.

"One guy made a rope tourniquet around my upper arm. He inserted a piece of wood, and twisted and twisted until my nerves cut against the bone. The hand was completely unusable for six months."

After some weeks, Dengler was handed over to the even fiercer Viet Cong. As they marched him through a village, a man slipped Dengler's engagement ring from his finger. Dengler complained to his guards.

They found the culprit, summarily chopped off his finger with a machete and threw him aside, handing the ring back to their horrified captive.

"I realised right there and then that you didn't fool around with the Viet Cong," he said.

Finally, Dengler arrived at his destination: a prisoner of war camp. "I had been looking forward to it," he said.

"I hoped to see other pilots. What I saw horrified me. The first one who came out was carrying his intestines around in his hands."

There were six other captives: four Thais and two fellow Americans, Duane Martin and Eugene DeBruin. One had no teeth – plagued by awful infections, he had begged the others to knock them out with a rock and a rusty nail in order to release pus from his gums.

"They had been there for two and a half years," said Dengler. "I looked at them, and it was just awful. I realised that was how I would look in six months. I had to escape."

As food began to run out, tension between the men grew: they were given just a single handful of rice to share while the guards would stalk deer, pulling the grass out of the animal's stomach for the prisoners to eat while they shared the meat.

The prisoners' only "treats" were snakes they occasionally caught from the communal latrine, or the rats that lived under their hut which they could spear with sharpened bamboo.

Nights brought their own misery. The men were handcuffed together and shackled to medieval-style foot blocks. They suffered chronic dysentery, and were made to lie in their excrement until morning.

After several months, one of the Thai prisoners overheard the guards talking.

They, too, were starving and wanted to return to their villages. They planned to march the captives into the jungle, and shoot them, pretending they had tried to escape.

Dengler convinced the others that now was the time to make their move. "I planned to capture the guards at lunchtime, when they put down their rifles to get their food. There were two minutes and twenty seconds in the day when I could strike."

In that time, Dengler had to release all the men from their handcuffs.

"The day came," he said. "The cook yelled 'chow time', and I let the handcuffs off. My heart was pounding, I slipped through a loosened fence, and seized three rifles."

He ran into the open, ready to capture the camp. But the others were nowhere to be seen – they had fled. Only Duane was beside him, vomiting with nerves.

Dengler raised a machine gun for the first time in his life. A guard was now two feet from him, waving a machete. Dengler fired.

Five dead guards lay at his feet, two others ran zig – zagging into the jungle. Duane and Dengler escaped into the wild; their fellow prisoners were never seen again.

"Seven of us escaped," said Dengler. "I was the only one who came out alive."

But escape brought its own torments. Soon, the two men's feet were white, mangled stumps from trekking through the dense jungle.

They found the sole of an old tennis shoe, which they alternated wearing, strapping it onto a foot with rattan for a few moments' respite.

In this way, they were able to make their way to a fast-flowing river. "It was the highway to freedom," said Dengler, "We knew it would flow into the Mekong River, which would take us over the border into Thailand and safety."

The men built a raft, and floated downstream on ferocious rapids, tying themselves to trees at night to stop themselves being washed away in the torrential water. By morning, they would be covered in mud and hundreds of leeches.

So weak that they could barely crawl up the river bank, the men eventually reached a settlement – but the villagers who greeted them were far from welcoming.

The pair knelt on the ground and pleaded. Dengler said: "One man had a machete in his hands. He swung and hit Duane's leg, and blood gushed everywhere. With the next swipe, Duane's head came off."

"I reached for the rubber sole from his foot, grabbed it and ran. From that moment on, all my motions became mechanical. I couldn't care less if I lived or died."

Miraculously, it was a wild animal who gave him the mental strength to continue.

"I was followed by this beautiful bear. He became like my pet dog and was the only friend I had."

These were his darkest hours. Little more than a walking skeleton after weeks on the run, he floated in and out of a hallucinatory state.

"I was just crawling along," he said. "Then I had a vision: these enormous doors opened up. Lots of horses came galloping out. They were not driven by death, but by angels. Death didn't want me."

It was five days later, on July 20th 1966, that Dengler heard an American airplane overhead and, summoning up his last reserves of strength, waved the parachute from an old flare that he had stumbled upon in the jungle to attract the pilot's attention.

The signal was spotted by Colonel Deatrick: Dengler's ordeal was at an end.

The stricken airman was taken to Da Nang Hospital in Vietnam, where he was interrogated by the CIA. In a further twist to his incredible tale, the pilot was sprung from their care by his fellow airmen, who wanted to bring him home.

They rustled him out of his hospital bed into a waiting helicopter and flew him to a hero's welcome aboard his naval carrier.

At night, however, he was tormented by awful terrors, and had to be tied to his bed. In the end, his friends put him to sleep in an cockpit, surrounded by pillows. "It was the only place I felt safe," he said.

Dengler recovered physically, but never put his ordeal behind him, retiring from the forces to become a civilian test pilot.

He said: "Men are often haunted by things that happen to them in life, especially in war. Their lives come to be normal, but they are not."

He lived out his remaining years in the San Francisco hills, marrying three times, before succumbing to brain disease aged 62.

He was buried with full military honours at Arlington National Cemetery in America, where a squadron of F14s flew over his grave in one final tribute to his remarkable break for freedom.

"Go to Original" links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted on VT may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the "Go to Original" links.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. VT has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is VT endorsed or sponsored by the originator. Any opinions expressed by the author(s) are not necessarily those of VT or representative of any staff member at VT.)

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy