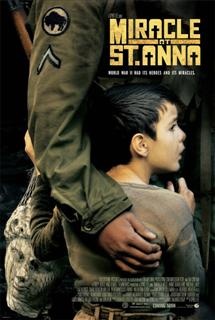

REVIEW: Miracle at St. Anna

REVIEW: Miracle at St. Anna

World War II Movie About Black Soliders in Itlay

A Move by Spike Lee

by Andrea Throckmorton

A murder committed by post-office worker Hector Negron in 1984 sets in motion an investigation that ties back to the experiences of a battalion of black American soldiers who became trapped in a Tuscan village during WWII.

The Emmy-winning "When the Levees Broke" and the box-office topping Inside Man have made Spike Lee one of the busiest independent director/producers on either coast (Lee has sequels to both projects in mind, too; in fact, IM 2 is being written right NOW!), and now he’s bringing a different WWII perspective to the big screen with Miracle at St. Anna. And he’s not stopping for air while taking swipes at Clint and the Coens and angering Italians for revising bits of their WWII history. So will some other sort of miracle earn Lee his first-ever Oscar?

Well, I imagine he has a better chance than, say, Oliver Stone this year, but a lot is riding on how Disney will market the film and how much of a push it will receive. (We hear Disney had to put the kibosh on Lee’s Eastwood comments, however, if he wants to make a good impression on the Academy — a move which might cause the director to abandon studio filmmaking for a spell?) Another factor not helping his campaign: The fact that Anna didn’t exactly stir audiences at its Toronto Film Festival premiere.

I mean, if this year’s Toronto International Film Festival had a subtitle, it could be "When Good Directors Go Bad." At least that’s what it has felt like around here as one anticipated new film after the next by some of the world’s name-brand auteurs—the Coen brothers, Spike Lee, Jonathan Demme—has laid a less-than-golden egg. And the younger directors one had harbored high hopes for? They’ve crashed and burned, too.

That was certainly the case with 32-year-old Peter Sollett, who followed up his promising 2002 debut, Raising Victor Vargas, with the noxious alt-romcom Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist. Where Sollett’s previous film was a rough-edged, richly observed portrait of a Dominican teenager coming of age on the streets of the Lower East Side, his latest is a self-consciously hip Juno knockoff that seems to have been made by, for, and about suburban teens who think they’re being original by wearing skinny jeans and listening to bands that advertise their super-secret shows on the walls of bathroom stalls (because putting up flyers or taking out an ad in the newspaper is, like, so five minutes ago).

And don’t even get me started about Lovely, Still—a first feature by 24-year-old director Nik Fackler screening in Toronto’s dubiously named "Discovery" section—which can best be described as a very poor man’s Away From Her as it might have been directed by a cut-rate M. Night Shyamalan. I realize the fact that this movie turns out to be about Alzheimer’s disease is supposed to be a surprise, but any film grotesque enough to use Alzheimer’s as a third-act, pull-the-rug-out-from-under-you twist deserves to have its beans spilled.

Still, at the mid-fest point, Toronto’s most crushing blows have been dealt by those filmmakers with the longest résumés and most gilded pedigrees, starting with Demme, whose fatuous Rachel Getting Married chronicles the reunion of a dysfunctional Connecticut clan on the eve of the eldest daughter’s nuptials. Call it My Big Fat United Nations Wedding: The bride is Jewish (and possibly recovering from an eating disorder). The groom is black. The wedding is Indian-themed right down to the bridesmaids’ saris. The maid of honor (Anne Hathaway) has just gotten out of rehab. A dead sibling looms large over the proceedings. And by the time the reception finally rolls around, Robyn Hitchcock (the subject of Demme’s 1998 concert film Storefront Hitchcock) and a New Orleans jazz band show up for extended musical interludes, by which point Rachel Getting Married has long ago stopped making sense. How former president Jimmy Carter (star of Demme’s 2007 Man From Plains) managed to avoid a cameo is something of a mystery.

Constantly teetering on the brink of hysteria and frequently tipping over into it, Rachel contains one 12-step program, two face-slappings, a car crash, an accidental drowning, multiple scenes of benevolent black folk (are there any other kind?) delivering soulful words of wisdom, and, before the end credits roll, copious tears and reconciliation. Some have likened Demme’s film to Noah Baumbach’s recent Margot at the Wedding, which is actually more like the kind of movie Demme used to make—the ones where the characters had edges and dimensions, and could be by turns loving and cruel, noble and deplorable. Here, we don’t doubt for a second that we’re watching a bunch of virtuous, good-hearted people who will manage to work out all of their problems, live happily ever after, and vote for Obama.

Lee’s Miracle at St. Anna isn’t quite as catastrophic, although, at nearly three hours, it’s almost as pointless. Lee has been publicly critical of Clint Eastwood for failing to include any African-Americans in his 2006 Iwo Jima diptych, but while Lee puts his buffalo soldiers front-and-center in this awkward hybrid of fable and WWII epic, the characters themselves are straight out of central casting: a smooth-talking Harlem lothario; an indignant polemicist; the requisite Uncle Tom; and a towering, soft-spoken "chocolate giant," as he is nicknamed by the young Italian boy whose lives the soldiers help to save in the titular Tuscan village. The motives of Lee’s film—to stake a claim for the black servicemen who fought and died for our country—are undeniably admirable, and the film itself (like all of Lee’s work) impeccably well-made. But this sliver of a narrative is the sort of thing Sam Fuller would have dispensed with in 80 minutes or so, whereas Lee hunkers it down with familiar wartime atrocities, flashbacks-within-flashbacks, and a wholly unnecessary wraparound story set in the 1980s.

Thankfully, not all of the masters present at Toronto this year have been throwing up bricks. France’s Agnes Varda returned to the festival with a lyrical, restlessly inventive memory film, The Beaches of Agnes, in which the octogenarian nouvelle-vague vet revisits hallmark locations from her life and career, including the small fishing village where she directed her first feature, La Pointe Courte, in 1954. It’s there, in perhaps the film’s loveliest sequence, that Varda tracks down the two young boys—now old men—seen pushing a hand-cart in one sequence from the earlier film and has them re-enact that scene, while a projector situated on the handcart broadcasts those half-century-old images onto a makeshift screen. Also in top form is the master American landscape filmmaker James Benning, who has declared that RR, his stirring ode to trains and the wide-open spaces they travel through, will be his last work shot on 16mm film; if so, that is our loss.

Heavyweight champ of the fest so far, however, is Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler, starring Mickey Rourke in a career-capping/resuscitating/redefining performance as an over-the-hill pro wrestler still grappling with opponents both physical and metaphysical. I will have more to say in the coming weeks, when The Wrestler makes its U.S. debut as the closing-night selection of this year’s New York Film Festival. But simply put: Who’d have thought that one of the great movies of Toronto (and the year) would turn out to be a wildly original, existentialist tragicomedy decked out in frosted-blond hair extensions and spandex tights?

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1046997/

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy