Leon Cooper, former Navy Ensign and amphibian boat commander, not only remembers the battle in November 1943, but is now fighting to clean-up the battlefield to make it a fit memorial for thousands who died there.

Garbage now litters the beaches on Betio Island in the Tarawa atoll, one of the bloodiest battles fought by Marines in WW II. The first amphibious assault against fortified positions in the Pacific War, it would serve as a model and lessons learned for future assaults. The 2nd Marine Division paid the price for the lessons .

.

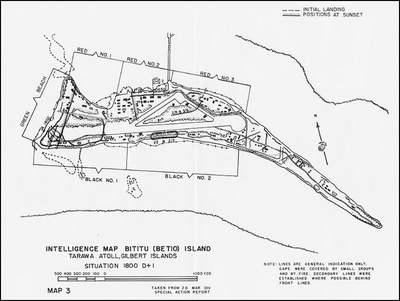

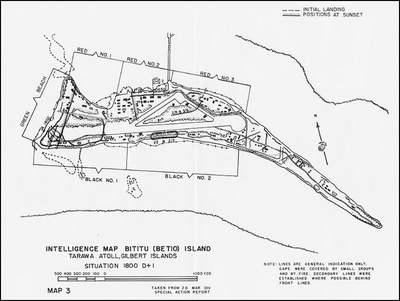

Located in the central Pacific, thirteen hundred miles northeast of the Guadalcanal, Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands was one of the bloodiest battles fought by the Marine Corps in WW II. The Japanese had established a defensive outpost on Betio Island three days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Using 4,000 Korean laborers, the Japanese built what looked like an impenetrable fortress on Betio, along with 4,000 foot airstrip for bombers.

In 1943, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff divided the Pacific Theater into two areas of operation. One area fell under the command of General Douglas MacArthur whose task was to attack the Japanese in New Guinea and the Philippines and eventually Japan; the other under Admiral Nimitz was designed to attack the Japanese through the Gilberts, Marshalls, and the Marianas in a leap frog fashion.

Betio’s Defenses

According to March 1944 Intelligence Bulletin: “The Japanese beach defenses consisted of well-emplaced and well-sited weapons, various types of  obstacles, and mines. The weapons included grenades, mortars, rifles, light and heavy machine guns, 13-mm dual-purpose machine guns, 37-mm guns, 70-mm infantry guns, 75-mm mountain guns (Model 41), 75-mm dual-purpose guns (Model 88), 80-mm antiboat guns, 127-mm twin-mount, dual-purpose guns, 140-mm coast-defense guns, and 8-inch coast-defense guns.”

obstacles, and mines. The weapons included grenades, mortars, rifles, light and heavy machine guns, 13-mm dual-purpose machine guns, 37-mm guns, 70-mm infantry guns, 75-mm mountain guns (Model 41), 75-mm dual-purpose guns (Model 88), 80-mm antiboat guns, 127-mm twin-mount, dual-purpose guns, 140-mm coast-defense guns, and 8-inch coast-defense guns.”

“The obstacles included pyramid-shaped, reinforced concrete obstacles, which were placed about halfway around the island on the coral reef; an antiboat barricade, made of coconut-palm logs: double-apron barbed wire; a perimeter barricade, constructed chiefly of coconut-palm logs; and antitank ditches, dug a short distance back of the perimeter barricade.

Antipersonnel and antiboat mines were laid on the fringing reef—frequently between the concrete obstacles—and on the beaches.” (See: http://www.lonesentry.com/articles/jp-betio-island/index.html)

The 2nd Marine Division, with the 2nd, 6th and 8th Marine regiments, would have to take Betio from the Japanese in November 1943. It was by all accounts a terrible ordeal, leaving over 1,150 dead and 2,300 wounded Marines in three days and almost the entire Japanese garrison of nearly 5,000 men, including several thousand Japanese Imperial Marines.

Betio is two miles long and a half of wide. New York’s Central Park is bigger.

Co ral Reef and Low Tide

ral Reef and Low Tide

Betio would prove to be three days of hell. The island was surrounded by a coral reef which prevented LCVP (Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel), flat bottom Higgens boats from entering the lagoon, except at high tide. At high tide there was 5 feet of water for the Higgens boats to cross over the reef. Naval intelligence expected the normal rising tide to allow larger landing craft to pass with room to spare. But on November 20th and 21st 1943, something called a neap tide phenomenon occurred, leaving a mean depth of just 3 feet over the reef. LCVPs got caught on the reef, making them perfect stationary targets for Japanese gunners.

Marines in the LCVPs, weighted down by their packs and equipment, would have to wade the 700 yards to the beach under constant artillery, motor, machine gun, and small arms fire. Many would be wounded or killed by enemy fire or downed in the attempt to reach the beach. In fact, casualties in the first wave of Marine battalions were as high as 75%.” (See: http://history.sandiego.edu/gen/ww2Timeline/Betio.html)

Others in the few LVT (Landing Vehicle Track) available for the assault would only get as far as the beach and then run smack into a five foot log seawall, which surrounded the entire island.

The 90 minute Naval bombardment managed to kill Admiral Shibasaki and key members of his staff, but very few of the enemy. Despite the questionable decision to invade Betio without LVTs for the entire invasion force and a heavy Naval bombardment, the Marines, at a tremendous cost in lives, defeated a tenacious enemy intent on fighting to the last man.

Robert Sherrod’s Witness

War correspondent Robert Sherrod had experience in covering the Aleutian Islands and the Navy raid on Wake Island. He went ashore with the Marines but nothing had prepared him for the terror he experienced. Tarawa was nothing like the Aleutians or Wake. Sherrod wrote Tarawa: The Story of a Battle in 1944. He would be very lucky to be alive:

"We jumped into the little tractor boat and quickly settled on the deck. ‘Oh, God, I’m scared,’ said the little Marine, a telephone operator, who sat next to me forward in the boat. I gritted my teeth and tried to force a smile that would not come and tried to stop quivering all over (now I was shaking from fear). I said, in an effort to be reassuring, ‘I’m scared, too.’ I never made a more truthful statement in all my life.

Now I knew, positively, that there were Japs, and evidently plenty of them, on the island. They were not dead. The bursts of shellfire all around us evidenced the fact that there was plenty of life in them!… After the first wave there apparently had not been any organized waves, those organized waves which hit the beach so beautifully in the last rehearsal. There had been only an occasional amphtrack which hit the beach, then turned around (if it wasn’t knocked out) and went back for more men. There we were: a single boat, a little wavelet of our own, and we were already getting the hell shot out of us, with a thousand yards to go. I peered over the side of the amphtrack and saw another amphtrack three hundred yards to the left get a direct hit from what looked like a mortar shell.

It’s hell in there,’ said the amphtrack boss, who was pretty wild-eyed himself. ‘They’ve already knocked out a lot of amphtracks and there are a lot of wounded men lying on the beach. See that old hulk of a Jap freighter over there? I’ll let you out about there, then go back to get some more men. You can wade in from there.’ I looked. The rusty old ship was about two hundred yards beyond the pier. That meant some seven hundred yards of wading through the fire of machine guns whose bullets already were whistling over our heads.

“The fifteen of us – I think it was fifteen – scurried over the side of the amphtrack into the water that was neck-deep. We started wading.”

Marines hunker down at the seawall

“No sooner had we hit the water than the Jap machine guns really opened up on us. There must have been five or six of these machine guns concentrating their fire on us… It was painfully slow, wading in such deep water. And we had seven hundred yards to walk slowly into that machinegun fire, looming into larger targets as we rose onto higher ground. I was scared, as I had never been scared before. But my head was clear. I was extremely alert, as though my brain were dictating that I live these last minutes for all they were worth. I recalled that psychologists say fear in battle is a good thing; it stimulates the adrenalin glands and heavily loads the blood supply with oxygen.

I do not know when it was that I realized I wasn’t frightened any longer. I suppose it was when I looked around and saw the amphtrack scooting back for more Marines. Perhaps it was when I noticed that bullets were hitting six inches to the left or six inches to the right. I could have sworn that I could have reached out and touched a hundred bullets. I remember chuckling inside and saying aloud, ‘You bastards, you certainly are lousy shots.’

After wading through several centuries and some two hundred yards of shallowing water and deepening machinegun fire, I looked to the left and saw that we had passed the end of the pier. I didn’t know whether any Jap snipers were still under the pier or not, but I knew we couldn’t do any worse. I waved to the Marines on my immediate right and shouted, ‘Let’s head for the pier!’ Seven of them came. The other seven Marines were far to the right. They followed a naval ensign straight into the beach – there was no Marine officer in our amphtrack. The ensign said later that he thought three of the seven had been killed in the water." (See: http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/tarawa.htm)

Robert Sherrod covered the rest of the Pacific War as an embedded correspondent with the Marines. He died of emphysema on February 13, 1994.

Ensign Leon Cooper

Young Leon Cooper, Navy amphibious boat commander, was another first eye witness to the enfolding tragedy. Volunteering for service in 1942, Cooper became in his words “a 90 day wonder,” commissioned as a officer in the Navy. Now, in his 80s, Leon Cooper returned to Betio in February 2008 after learning that the beach were so many gave their lives was a garbage dump. The trip to the island was recorded in a documentary at part of the effort to raise funds to clean-up the island and erect a proper memorial for the dead (See: http://www.returntotarawa.com)

Leon Cooper is obviously an intelligent man who keeps the language in the documentary salty and right on target. Any Marine would understand Cooper’s motives in producing this film and instinctively like him. At one point in the documentary, Cooper recalls his Higgens boat hung up on the reef, sees the deadly trap set for the Marines in the boat, and manages to get the boat off the reef and into the lagoon. You have to admire the man’s courage and determination. (See: http://www.snagfilms.com/films/title/return_to_tarawa/)

The tragedy is that “hundreds of Americans still lie in Betio,” according to Mr. Cooper.

"It is particularly contemptuous to treat WWII MIAs as if they were fossilized remains. The Defense Department’s recovery rate of 0.2% per year of WWII MIA ‘returns’ simply emphasizes the Department’s contempt," states Cooper. One study has estimated that, at the Department’s recovery rate, it will take more than 300 years to recover all of the Pacific War MIAs that are "recoverable." He goes on to say, "Will the thousands of Americans who still lie where they fell in Papua New Guinea, in the Solomons, in the Philippines, in the Marianas, and in the many minor land skirmishes ever be returned to their homes?"

Copies of Leon Cooper two books, 90 Day Wonder – Darkness Remembered, and The War in the Pacific – A Retrospective, are available upon request. For further information visit his Web site at: http://returntotarawa.net.”

Robert O’Dowd served in the 1st, 3rd and 4th Marine Aircraft Wings during 52 months of active duty in the 1960s. While at MCAS El Toro for two years, O’Dowd worked and slept in a Radium 226 contaminated work space in Hangar 296 in MWSG-37, the most industrialized and contaminated acreage on the base.

Robert is a two time cancer survivor and disabled veteran. Robert graduated from Temple University in 1973 with a bachelor’s of business administration, majoring in accounting, and worked with a number of federal agencies, including the EPA Office of Inspector General and the Defense Logistics Agency.

After retiring from the Department of Defense, he teamed up with Tim King of Salem-News.com to write about the environmental contamination at two Marine Corps bases (MCAS El Toro and MCB Camp Lejeune), the use of El Toro to ship weapons to the Contras and cocaine into the US on CIA proprietary aircraft, and the murder of Marine Colonel James E. Sabow and others who were a threat to blow the whistle on the illegal narcotrafficking activity. O’Dowd and King co-authored BETRAYAL: Toxic Exposure of U.S. Marines, Murder and Government Cover-Up. The book is available as a soft cover copy and eBook from Amazon.com. See: http://www.amazon.com/Betrayal-Exposure-Marines-Government-Cover-Up/dp/1502340003.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy