by Anthony J Hall

Many of the same forces that make North America a primary aggressor in contemporary processes of colonization abroad are also operative in the internal colonization of the continent’s First Nations. This article explores the dynamics of this internal colonization by looking at the treatment of Aboriginal fishers in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest of the United States.

treatment of Aboriginal fishers in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest of the United States.

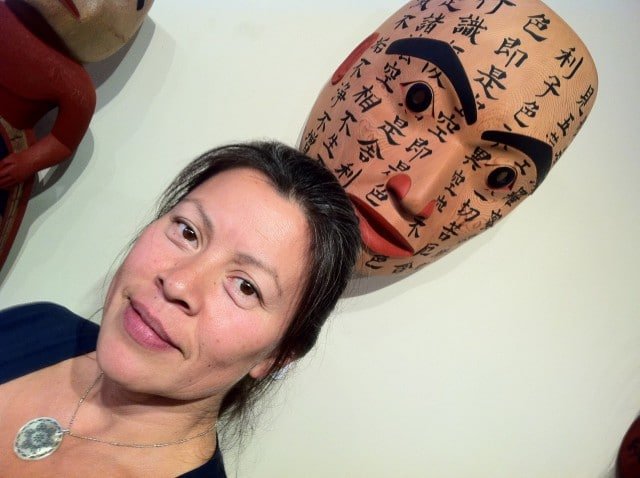

The Case of Kwitsel Tatel

Canada’s international reputation should rightfully be made to suffer infamy for the federal government’s treatment of First Nations Indian, Inuit and Metis peoples. Canada’s highest law describes this amalgam of groups as the Aboriginal peoples. The litany of federal crimes against Aboriginal peoples includes the Canadian government’s resort to the criminal courts where the prosecutors of the federal Crown attempt, case by case, to narrow judicial interpretation of sections 35 of Canada’s self-described supreme law. According to this provision of the Canadian constitution, “the existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of Aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.”

In order to illustrate my argument I shall make reference to the criminalization of Patricia Kelly, whose Coast Salish name is Kwitsel Tatel. Kwitsel Tatel’s experience is illustrative of a larger pattern that repeatedly points the litigious machinery of federal authority against some of the most important affirmations of human rights in the Canadian constitution. Kwitsel Tatel’s case is revealing for what it exposes about the political manipulation by the Canadian government of the criminal justice system in Canada’s westernmost province. It seems that almost anything goes when it comes to advancing the lie that it is law rather than theft governing the appropriation of resources from Aboriginal peoples. This cycle of legalized theft in British Columbia continues patterns of colonization initiated with Spain’s attempt to conquer, enslave, exterminate, and dispossess the Indigenous of the Americas beginning in 1492.

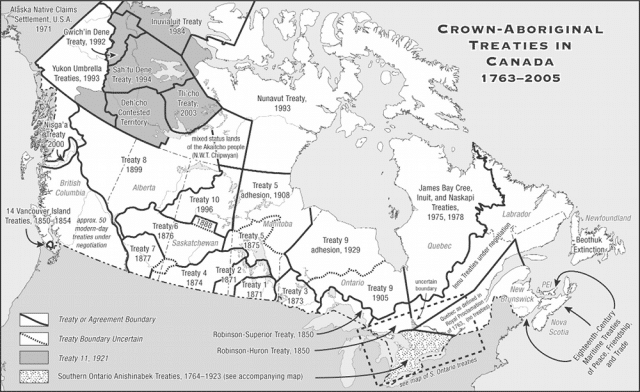

This criminalization of Kwitsel Tatal for possessing fish is taking place in a province where the disposition of title to lands, waters and resources is presently subject to negotiation between the Crown and Indigenous peoples. Since its founding in the mid-nineteenth century, British Columbia developed outside the rule of constitutional law stipulating that Indian consent must be obtained in British North America before non-Indian forms of settlement, land tenure and resource extraction can be enacted and advanced. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 is the major source of this constitutional requirement that Aboriginal consent must be obtained for the expansion of Euro-American settlements. King George III’s Royal Proclamation of 1763, which established the constitutional foundations of Quebec and of British imperial Canada, was a major provocation of the secessionist movement whose leaders delivered their political manifesto to the world on July 4, 1776 in the form of the American Declaration of Independence.

The belated effort to bring British Columbia within Canada’s rule of law is marked by the Crown-Aboriginal treaty negotiations covering the largest part of BC’s mountainous terrain as well as its rivers, lakes, and coastal waters. As demonstrated by the criminalization of Kwitsel Tatel and others for exercising their Aboriginal right to fish in their Aboriginal waters, the integrity of this contemporary process for making Crown-Aboriginal treaties is undermined because Crown officials are exploiting the criminal justice system to predetermine the outcome of negotiations with First Nations in BC. Through the coercive intervention by the RCMP, the federal Department of Fisheries, the federal Justice Department, and provincially-appointed judges, the criminalization of Kwitsel Tatel has become an integral part of the unfair, inequitable and therefore tainted BC treaty process.

I shall contrast Ms. Kelly’s treatment by the criminal justice system in Canada to the treatment extended Coast Salish people in the Pacific Northwest of the United States when their treaty rights to fish were affirmed in 1974 in the ruling of Judge George Boldt in the US District Court in the case of USA versus Washington. The US federal government took Washington state to court in 1970 to respond affirmatively to fish-ins that highlighted the contention of Indigenous peoples in the Pacific Northwest that their treaty rights to fish were being violated.

Kwitsel Tatel’s case demonstrates that in Canada the federal authority is following the opposite track to that of US federal government. The federal authority of Canada is not living up to both its fiduciary and section 35 responsibilities to protect Aboriginal peoples from violations of their existing Aboriginal and treaty rights. Indeed, the very federal government that is supposed to shoulder these responsibilities has put itself on the dark side of the law. Canada’s federal Justice Department has joined with those who seek to advance the extinguishment of section 35 rights in order enrich more quickly those transnational corporations who look to the provincial legislatures for their charters empowering them to extract and privatize natural resources.

By consistently opposing in court affirmative interpretations of section 35, Crown officials in Canada set a terrible example for the Canadian people. If even the Queen’s own advisers refuse to demonstrate what it means to recognize and affirm the existence of Aboriginal and treaty rights in test cases, why should Canadian citizens rise to a higher standard in their day-to-day dealings with Aboriginal peoples? Why should Canadians respect Canada’s constitution when it seems the Canadian government demeans, disrespects and frequently violates key aspects of a document that describes itself as Canada’s supreme law? This assault on rights is also an assault on Aboriginal peoples, the very groups whose communities already suffer the highest rates of poverty, suicides, addictions, domestic violence, and incarceration.

[youtube S2UMgov3k-Y]

The federal effort to criminalize Kwitsel Tatel and hundreds of other First Nations people throughout Canada for exercising their Aboriginal and treaty rights is one small part of a dark process that is filling Canadian jails especially in Western Canada with disproportionately high numbers of Indian, Metis and Inuit individuals. This federal push to deny and negate rather than recognize and affirm Aboriginal and treaty rights is part of a scandal of law enforcement marked by a stunning lack of protection especially for Aboriginal women in western Canada.

This failure of protection goes far beyond the propensity of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to side with those who violate Aboriginal and treaty rights. In its entire history when has Canada’s federal police force ever intervened even once to enforce a positive affirmation of the Canadian constitutional law of Aboriginal and treaty rights? What government, corporation, or individual has ever been criminalized for violating the constitutionally-protected existence of Aboriginal and treaty rights? This failure of protection cuts beyond legal abstractions to affect conditions governing the lives and deaths of Aboriginal peoples, far too many of meet very violent ends.

Hundreds of Aboriginal women have been made to disappear in Canada in a predatory frenzy involving circumstances that go largely uninvestigated or inadequately investigated. This failure of protection is epitomized by the feeding of dozens of Aboriginal sex trade workers into the slaughtering machines of a Vancouver-area pig farmer named Robert Pickton. The RCMP delayed pressing charges on Pickton for several years even though the relatives of the victims supplied police with plenty of evidence of what was taking place. Who were police and Crown prosecutors trying to protect by holding back from responding to a widely-shared secret that something was terribly wrong at “Piggies,” at Pickton’s after-hours party emporium where some prominent Vancouverites joined the hoypoloi in the quest for fun and excitement?

Fish Farms and Wild Salmon

Over the past decade Kwitsel Tatel has experienced what it means to be criminalized by a system of law enforcement that affords little protection for the very persons of Indians, Inuit and Metis let alone for their constitutionally-affirmed Aboriginal and treaty rights. A member of the Sto:lo Nation of Coast Salish people, Kwitsel Tatel has spent almost a decade in and around the provincial court of Chilliwack British Columbia trying to defend herself from charges mounted by the Federal Department of Fisheries, the RCMP, and the federal Justice Department. As the Sto:lo matriarch sees it, Kwitsel Tatel would betray the legacy of her ancestors, but especially that of her fisher mother, by paying the $200 fine to signify her agreement that she is guilty of a crime of possessing salmon that she harvested from the Fraser River. She would also betray her posterity by giving into the federal Crown’s effort to deny and negate the viability of her people’s Aboriginal fishery.

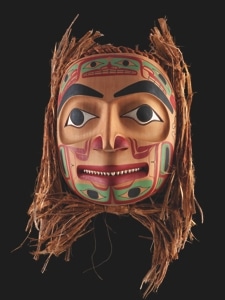

A single mother of two teenagers, Kwitsel Tatel has represented herself in the legal proceedings. She has not received any monetary backing from federally-funded or provincially-funded Aboriginal organizations who unfortunately are sometimes subject to political manipulation by their paymasters. Kwitsel Tatel has consistently contended that the federal charge against her violates the activity that she views as the very core of her Aboriginal rights whose existence is recognized and affirmed in the Canadian constitution. Since time immemorial the rich fisheries of the west coast region of North America have offered up the main supply of sustenance for Kwitsel Tatel’s people. Indeed, these fisheries reside at the cultural heart of Aboriginal orientations to the spiritual ecology of this region’s rich Aboriginal environment.

Kwitsel Tatel has been made to pay a high price for continuing the heritage of her ancestors in British Columbia by exercising her Aboriginal right to fish even in the face of aggressive shows of force by the RCMP and federal Department of Fisheries who have sided with the farmers of  domesticated fish in BC’s coastal waters. These fish farms have been sources of infestation and sickness for the wild salmon populations.

domesticated fish in BC’s coastal waters. These fish farms have been sources of infestation and sickness for the wild salmon populations.

By favouring fish farmers over Aboriginal harvesters of the wild salmon, law enforcement officials are replicating old patterns that formerly saw the US and Canadian governments band together with the railway companies to favour termination of the wild buffalo herds of the prairies. Like the wild buffalo populations once did, the wild salmon populations currently give some Indigenous peoples in BC a means of maintaining a degree of economic independence. The political economy of harvesting wild salmon in Aboriginal fisheries runs contrary to the policies of institutional assimilation that prevail still. Thus the propensity has been to replace wild salmon with farmed salmon, much like the wild buffalo herds were replaced with privatized animal husbandry, in continuing the genocidal legacy of nineteenth-century Aboriginal policies.

Because of her alleged crime of harvesting and possessing wild salmon Kwitsel Tatel has faced incarceration where she was subjected to the indignity of vaginal and anal inspections. Her picture appeared in a publication called Crime Stoppers, a police snych line. With her having been branded as a criminal in Crime Stoppers and with requirements to appear in court almost 200 times in the last decade, Kwitsel Tatel’s employment opportunities have been severely limited.

The plunge of Kwitsel Tatel into joblessness helps illustrate how the criminalization of targeted groups and individuals tends both to breed and reflect poverty even as it is an outcome and driver of racism. To be criminalized by the criminal justice system is to be placed on the far side of a line where predators inside or outside the police tend to enjoy impunity from prosecution. This propensity was illustrated last autumn when the RCMP’s heavily-armed units for policing Indian people in the Fraser Valley area were turned on Kwitsel Tatel’s home with the apparent intention of apprehending her children. What does this kind of police intervention do to relationships within the targeted family and between the members of the targeted family with the rest of the community? Only a deft and timely intervention by a friend and family member, Chief June Quipp, averted a tragic outcome.

From the Washington State Fish-Ins of the mid-1960s to the Boldt Decision in the Case of USA versus Washington State

The most watched and performed Washington state fish-ins took place in the mid-1960s when Aboriginal fishers and some of their allies purposely courted arrest by Washington state police to dramatize their contentions that their treaty rights were being violated. The Aboriginal fish-ins attracted broad support from within Native American communities and from church groups and celebrities. Near the animating heart of this confederacy of shared purpose was a strong partnership linking the legendary Hollywood movie star, Marlon Brando, with Puyallup leader, Robert Satiacum. A gifted student of the nexus between commerce and law, Satiacum sought to improve the economic life of his people by exploiting fully the reference in the section 2.3 of the US Constitution to “Indians not taxed.”

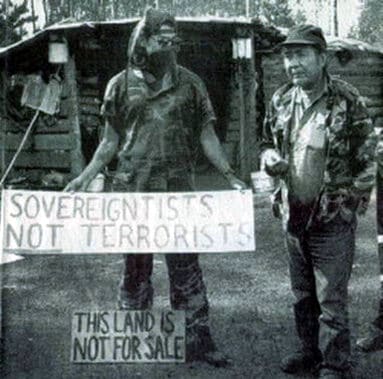

In retrospect the Washington state fish-ins helped channel the energy from a growing movement of activists intent on extending the worldwide movement for an end to colonialism into the inner organization of North American society. The spirit of what began on the rivers of Washington state would in later years give rise to a Native American occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969, the Washington DC-bound Trail of Broken Treaties in 1972, the symbolic return to Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in 1973, and AIM’s occupation of Anicinabe Park in the Kenora region of northwestern Ontario in 1974. From this trajectory of activism and from the networking of Native American activists inside the prisons of Canada and the United States emerged the American Indian Movement, AIM, one of the main groups targeted for infiltration and sabotage by the J. Edgar Hoover’s Federal Bureau of Investigation’s COINTELPRO program.

AIM was devoted to asserting the sovereignty and self-determination of  Indian communities in North America and the international community. AIM’s spokespersons, including Dennis Banks and Russell Means, argued that the sovereignty of Indian nations was demonstrated by the existence of 400 or so treaties transacted with the US government. These agreements with First Nations had been ratified in Congress in the same way as US treaties with foreign countries. The federal effort to destroy AIM through tactics of police infiltration and the criminalization of its leadership, sometimes through the manufacturing of false evidence, demonstrates patterns of interaction with the criminal justice system that most likely remain operative to this day.

Indian communities in North America and the international community. AIM’s spokespersons, including Dennis Banks and Russell Means, argued that the sovereignty of Indian nations was demonstrated by the existence of 400 or so treaties transacted with the US government. These agreements with First Nations had been ratified in Congress in the same way as US treaties with foreign countries. The federal effort to destroy AIM through tactics of police infiltration and the criminalization of its leadership, sometimes through the manufacturing of false evidence, demonstrates patterns of interaction with the criminal justice system that most likely remain operative to this day.

British Columbia has been one of the jurisdictions where the criminal justice system has been subverted to advance the assault on AIM. For instance, Leonard Peltier was extradited from British Columbia in 1976 based on the false testimony given to Canadian officials by federal officials in the United States. Peltier would become one of the most famous political prisoners in the world, a frequent topic of discussion, for instance, in the summitry between US president Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Peltier is widely seen to have been framed by the US government for the murder of two FBI agents at Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota in 1975.

BC is also the site of from which John Graham was extradited in 2007 to South Dakota to face charges that he had murdered Micmac Indian and AIM activist, Anna Mae Aquash. The case by US federal prosecutors against Graham characterizes the homicide of Aquash as a recrimination on behalf of AIM’s inner security unit against a suspected police informant. Whatever happened, the evidence is overwhelming that covert police infiltration of AIM was so deep and severe that it became impossible to for members of the organization to collaborate constructively.

Among the key supporters of the Washington state fish-ins was the Episcopal minister John Yaryan who was arrested along with Marlon Brando and dozens of others in the course of the spectacle. On behalf of the American Friends Service Committee, the Quakers, Dr. Evans Roberts was also instrumental in assembling, interpreting and disseminating information essential to the mobilization of public opinion in support of the Aboriginal and treaty rights of North America’s First Nations.

As the Washington state fish-ins moved from the rivers to the courts the US Justice Department increasingly took the side of the Native Americans beginning with amicus curiae interventions. It was Attorney-General Robert Kennedy who moved first to assert federal authority in the defense of Aboriginal and treaty rights from state incursions. Ramsay Clark, Kennedys’ friend and his successor as US Attorney-General, continued this push that would culminate in 1970 in the historic decision of the US Justice Department to take Washington state to court for violating treaties contracted in the 1850s that recognize Aboriginal rights to fish even off their reservations.

In the journal, Cultural Survival, Peter Knutson has described the significance of the federal stance in the case of USA versus Washington state as follows:

The federal intervention in the Washington State salmon fishery was necessary to protect the culturally unique relation of Indian people to the salmon resource. According to their argument, salmon is at the core of a culture complex; not only does it provide economic sustenance for tribespeople, but through participation in the harvest, it provides a focus for personal and collective identity. Given democratic commitment to the rights of the minority, the federal government must intervene to protect the rights of cultural minorities.

Ramsay Clark has been a close observer of the treatment by Crown officials of the issues pertaining to the contested titles to the lands, waters and natural resources of British Columbia. His level of involvement grew in 1995 when his client, Splitting The Sky, emerged as a key figure in the Gustafsen Lake Indian War on lands that had been the site of an AIM-inspired sundance ceremony. In the course of this contention the sundancers’ lawyer, Dr. Bruce Clark, was sent by a judge for a mental examination in the course of his presentation aimed at bringing forward the argument he developed in his Ph.D. thesis.

The main thrust of Clark’s argument is that politics has been allowed to prevail over a dispassionate reading of the law in the role afforded to the criminal justice system in Canada in dealing with contending interpretations of the BC title issue. Clark went as far as to challenge the jurisdiction of BC’s courts in these matters. In looking over what had transpired in the armed confrontation at Gustafsen Lake, where Crown officials deployed land mines against the self-declared Ts’peten Defenders, the former chief law enforcement officer of the United States observed, “In the course of the [Gustafsen Lake] standoff Canada deployed all the violence, deception, wiles and corruption learned from five hundred years of experience in crushing Indian peoples.” (Hall, Earth into Property, p. 583)

I became involved in the Gustasen Lake conflict when I wrote about the deeper constitutional issues entailed in the confrontation in an opinion piece that appeared in the The Globe and Mail on September 5, 1995. Five years later I wrote an expert opinion for a court case involving an application from Canada to the United States to extradite James Pitawanakwat from Portland Oregon. At the time Pitawanakwat had moved to Portland having jumped his probation for the crimes committed at the Gustafsen Lake Indian War.

I was asked by the Federal Public Defender’s office representing Pitawanakwat to address the so-called political offenses exception clause of the Canada-US Extradition Treaty. In the case of USA versus Pitawanakwat Judge Janice Stewart wrote a ruling that concurred with my own expert opinion on several key points. In a reversed outcome to the process that had taken place when Leonard Peltier had been extradited from British Columbia to the United States in 1976, the application by the US State Department to extradite Pitawanakwat back to Canada was denied. Judge Janice Stewart had been persuaded that the conviction of Pitawanakwat in the criminal justice system of British Columbia had been tainted by political factors.

Among these factors was a huge media campaign in 1995 when an RCMP officer was caught on camera describing his force’s “smear and disinformation campaign.” (Hall, Earth into Property, 578- 584) As a result of this process James Pitawanakwat was granted asylum in the United States from the politically-tainted criminal justice system in British Columbia. This ruling in a US court on issues arising from the contested title to the lands and waters of British Columbia in my view helps demonstrate the international character of the some of the issues that still await resolution.

The Criminalization of Aboriginal Peoples as an Tactic of Colonization and Dispossession

Ramsay Clark’s comment about the legacy of more than five centuries of crushing Indian people is very pertinent to the treatment of Kwitsel Tatel by Canada’s criminal justice system. The process of invoking the power of the law to justify the appropriation of Aboriginal resources and to suppress Aboriginal resistance to these assaults has long been an integral feature of colonization and imperial expansion. Some aspects of the founding of the United States epitomize this process.

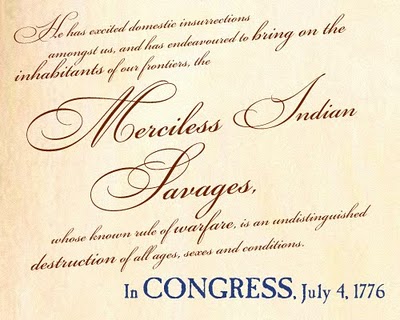

The USA was founded on a primal criminalization of those Indigenous peoples that were the primary obstacles to the new republic’s transcontinental expansion. The founding manifesto of the USA, the American Declaration of Independence, included a provision condemning King George for the alleged crime of “bringing on the merciless Indian savages whose known rule of warfare is in an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions.” This early example of racial profiling, a classic illustration of the same mindset driving forward US suspension of the rule of law in the name of the so-called Global War on Terror, was a direct response to the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Based on the principle that Aboriginal consent must be obtained before the expansion of Euro-Americans settlements could go forward, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 detailed a plan to regulate western expansion and outlaw the anti-Indian vigilantism of the Anglo-American frontier.

George for the alleged crime of “bringing on the merciless Indian savages whose known rule of warfare is in an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions.” This early example of racial profiling, a classic illustration of the same mindset driving forward US suspension of the rule of law in the name of the so-called Global War on Terror, was a direct response to the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Based on the principle that Aboriginal consent must be obtained before the expansion of Euro-Americans settlements could go forward, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 detailed a plan to regulate western expansion and outlaw the anti-Indian vigilantism of the Anglo-American frontier.

The regime of Crown-Indian relations set in motion by the Royal Proclamation was an important factor in the decision of many Aboriginal peoples in the era of the American Revolution and the War of 1812 to ally themselves with the military forces of the British imperial Crown and against those of the Anglo-American rebels. The US military assault on the Indian fighting forces answering Tecumseh’s call to arms was justified in the language of criminalization. In describing the Aboriginal defenders of Canada, Lewis Cass, a former governor of Michigan Territory and future candidate for president of the United States, condemned the Indian Confederacy as “deserters of a few tribes.” Cass continued, “The acknowledged government of each tribe disavowed any participation in their projects. And they were in fact a lawless predatory band, obeying no common authority, and seeking no common authority, and seeking no rational object.” (Hall, Earth into Property, 280)

The execution of Louis Riel for treason in 1885 by the Dominion of Canada epitomizes the criminalization of Aboriginal resistance to the colonial assault on Aboriginal and treaty rights. Riel led his movement of Metis resistance to the negation of his people’s rights and titles in the era when the Canadian government ceased treating Indigenous peoples like allies of the Crown and instead began treating them as wards of the federal authority. The replacement of the regime of the Royal Proclamation with that of the Canadian parliament’s Indian Act would prove to have disastrous consequences for Indigenous peoples.

Part of the transformation of Indigenous peoples from allies of the Crown to wards of the Canadian state involved the criminalization of the natural leadership of Aboriginal peoples. For instance, the same process of federal criminalization experienced by Riel was also directed at Big Bear and Poundmaker, both of whom had tried to hold back young Cree warriors from joining the Metis resistance of 1885. At his his trial in Regina Riel referred to the process whereby Canadian authorities “began by treating the leaders of the small community as bandits, as outlaws, leaving them without protection, they disorganized that community.” (Hall, Earth into Property, 585-586)

The effects of this abuse of law in stripping away protection and leadership from Aboriginal communities is everywhere on sorry display in the high rates of Aboriginal poverty, unemployment, incarceration, addictions, suicide and domestic violence. What do we convey to our youth when police choose to publish Kwistel Tatel’s photograph in Crime Stoppers rather than devote energy to determining what it means for law enforcement officials, but especially Crown prosecutors, that the highest constitutional law in Canada calls for the recognition and affirmation of the existence of Aboriginal and treaty rights? Clearly we still have not transcended our national schizophrenia that reveres Riel as a founder of Manitoba and of Canada who was nevertheless executed Dominion authorities for treason.

There was a major push to criminalize Robert Satiacum in the years following the Boldt ruling and its confirmation by a higher court in the case of USA versus Washington state. I suggest the background of this process of criminalization where I write in Earth into Property, Colonization, Decolonization, and Capitalism, “Satiacum acquired powerful new enemies once he pressed his legal arguments beyond Indian gaming and tax-free sales of tobacco and alcohol to attempt a fundamental reordering of the tax structure of the US oil and gas industry.” (p. 582) Much of this process of criminalization took place in the criminal justice system of British Columbia where Satiacum was jailed for a time. He also established a precedent in Canada-US relations when a lower court extended Satiacum the status of a refugee in 1987.

The process of criminalizing efforts to advance the internationalization of Aboriginal and treaty rights in Canada has been extended to at least three lawyers in British Columbia. According to the 1994 affidavit of lawyer Jack Cram, “Dr. Bruce Clark, Renate Andres-Auger and myself have all seen the inside of a jail cell” for raising issues concerning the relationship between sovereignty and the unceded land title of most Aboriginal groups in BC. (Affidavit of Jack Cram, 30 May, 1994, 18)

The Nexus of the Title Question and the Criminal Justice System in the History of British Columbia

The criminalization of Kwistel Tatel in a Chilliwack court puts on clear display the troubled connection between the criminal justice system in British Columbia and the unresolved nature of title to lands and resources in Canada’s westernmost province. This connection has been a consistent feature of the political culture of British Columbia when a fur trade domain was transformed into a full-fledged colony of Great Britain in 1858 in response to a rush of Californian gold seekers into the valley of the Fraser River and its tributaries.

In the early days of British Columbia there was much reference to the ideals of even-handed British justice being made to apply equally to all inhabitants of the colony. The statistics, however, do not bear out this principle. Between 1859 and 1870 BC’s first judge, Matthew Begbie ordered the hanging of 26 people, 22 of them Indians, 3 of them Chinese, and one of a person of European ancestry. Among those hanged were five Chilcotin men who in 1864 were found guilty by Judge Begbie for killing some of the builders of a road into their territory. There was no serious grappling at the time with the issue of whether these doomed men had engaged in a legitimate act of self-defense from a genuine assault on their people and territories.

In looking back at this history of hanging in colonial BC Sidney L. Harring, a US-based legal historian has written, “There is no parallel to these executions anywhere in the hundred colonies that Britain founded, even in the penal colony of New South Wales; they make the founding of British Columbia a bloody colonial enterprise. But that violent history was ‘legal,’ each with executions ordered by a British judge.” (Harrings White Man’s Law cited in Hall, Earth into Property, 373)

Many have asked why Crown officials applied the terms of the Royal Proclamation to treaty negotiations with Indigenous peoples east of the Rockies but not to the Indians of British Columbia. To me the answer can be summed up in two words: the Royal Navy. As the Dominion of Canada extended its presence into the vast territories its agent had acquired from the Hudson’s Bay Company they were very vulnerable to the incursions of disaffected Indians. This strategic consideration was a factor in the negotiation of eleven numbered treaties and adhesions that were negotiated between 1871 and 1929.

In the coastal regions of British Columbia the power of the Royal Navy made it easier for Crown officials to escape some fundamental reckoning with the title issue, although BC’s founding governor, James Douglas, did order the negotiation of Crown-Aboriginal treaties in the immediate vicinity of the colonial capital of Victoria. By and large the navy asserted the Crown’s might with ceremonial displays of its ships’ firepower. In 1863, however, a naval battle did take place between the war canoes of the inhabitants of a Salish village on Kuper Island and the Royal Navy’s gunboat Forward.

Although the title question was not negotiated in a comprehensive fashion throughout the early decades of BC history, there was plenty of agitation advancing all sides of the issue. This intensity of the debate about what to do was captured in a collections of documents published by the BC Legislature in 1876. That document is entitled Papers Connected to the Land Question, 1850-1875. That collection of documents demonstrates the complexity of the legal and political issues concerning Aboriginal title to the lands and waters during a period when British Columbia was subject to a wide variety of jurisdictional claims. Over the course of this quarter century between 1850 and 1875 these claims included those of Great Britain, the Hudson’s Bay Company, the colony of Vancouver Island, the colony of British Columbia, the province of British Columbia, the Dominion of Canada and, of course, the many Aboriginal nations and confederacies of people possessing the oldest titles of all.

The title issue became mired in efforts in the mid-nineteenth century to decentralize the organization of the British Empire. This modernized empire of free trade was supposed to decrease the expense of colonial administration. The result was a clear conviction on the part of the imperial government that the Indigenous peoples should be dealt with but that it was the responsibility of the local government to pay the expense of the treaty transactions. Not surprisingly this proposal did not go over well with many non-Indian inhabitants of BC even though they were strongly outnumbered by the Indigenous peoples throughout much of the nineteenth century.

British Columbia entered the Dominion of Canada in 1871 on the condition that a transcontinental railway be built to connect the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean. In the early years the government of Canada tried to force some reckoning with the title issue on the government of British Columbia but to no avail. The seriousness of the issue came to light in 1871 when the Dominion government used its constitutional power to disallow provincial legislation that ignored the title of the Indigenous peoples.

The Papers Connected to the Land Question was suppressed in the early years of the twentieth century to keep the important document out of the hands of an emerging Indian leadership seeking resolution to the title question. Efforts were made to undermine this leadership by deploying the federal Indian Act as weapon to criminalize the raising of money by Indian people to pursue any Indian claim of any kind. This provision came into force in 1927 six years after the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, then the highest court on the British Empire, affirmed the existence of “the native title to land” in the case of Amodu Tijani versus, The Secretary, Southern Nigeria. By criminalizing Indian political processes and trying to keep crucial information away from Indian leaders, Crown officials tried to block any process that might lead to the Nigerian precedent being applied to the title of BC’s lands and waters.

The Role of Christian Religion in the BC Title Issue

Some Christian missionaries became important allies of Indigenous peoples in their quest for recognition of their title to their Aboriginal lands and waters. This heritage of collaboration forms one the brighter streams of interaction with Indigenous peoples in efforts to Christianize the Aboriginal populations of the Americas. The Protestant missionary, Jeremiah Evarts, presented one the most exemplary role models in this history of Christian efforts to recognize and affirm the existence of Aboriginal and treaty rights. Using the nom de plume of William Penn, the Quaker leader known for making treaties with the Aboriginal residents of Pennsylvania, Reverend Evarts led the campaign to oppose the Indian removal policies pressed forward in the United States after Andrew Jackson was installed as US president in 1828.

Some of the Anglican missionaries to British Columbia have tended to be particularly intent on applying to the development of BC the principles of Aboriginal title as codified in the Royal Proclamation. The fact that the British imperial monarch is also the head of the Church of England helped contribute to this propensity. Many of these forces met in the activism of Rev. Arthur O’Meara who was a clergyman, a lawyer, and secretary of the Allied Tribes of British Columbia founded in 1916. A Haida graduate of the Coqualeetza Residential school in Sardis, The Reverend Peter Kelly was another strong Christian advocate of the need to apply the Royal Proclamation to BC.

Throughout the late nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth century various Aboriginal delegations sought recognition of their Aboriginal title by visiting the Governor-General in Ottawa and various officials in Great Britain including the monarch. One of the powerhouses of organization and activism to emerge from these processes was Andy Paull. A clerk in a law office, Paull would not become a lawyer although he was qualified to do so. In order for him to become a lawyer in those days Paull would have had to become an enfranchised citizen of Canada and thereby cease to be a registered Indian. The sharp distinction between registered Indians and Canadian citizens remained absolute until the 1960s. One could not be both concurrently.

Even now the relationship between Indian status and Canadian citizenship remains a twilight zone of constitutional uncertainty. As some Indian people in BC see it, they will not embrace Canadian citizenship until their relationship with Canada is formalized through some sort of treaty relationship with the Crown. As other First Nations people see it, they do not want their Aboriginal group to make a treaty. Rather they want to negotiate ways that will enable them to draw economic activity from ways of exercising their unceded title in their Aboriginal lands and waters.

Andy Paull was able to negotiate around the Indian Act’s prohibition on advancing Indian claims by doing some of his activism under the cover of his work as a coach of the North Shore Indians lacrosse team. Many on his team were Iroquoian people from the bigger reserves in Ontario and Quebec. Andy Paull received some support for his political and legal work from the Roman Catholic Church. So too did his associate, Jules Sioui, a Huron man from a small Roman Catholic reserve in the area of Quebec City area. There has sometimes been a Roman Catholic undercurrent to some Indian resistance to colonization by a Protestant majority in Washington Territory and British Columbia.

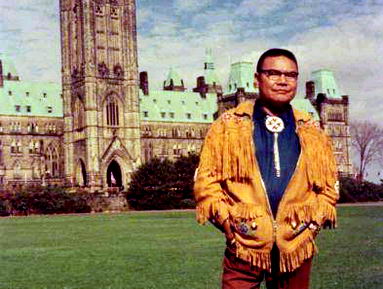

From the Shuswap Country of British Columbia to the World Council of Indigenous Peoples: George Manuel and the Fourth World

Andy Paull helped mentor and advise George Manuel who emerged from Shuswap Territory in the BC interior to become one of the most important political figures that Canada has ever produced. After changes to the Indian Act that lifted the prohibition on advancing Indian claims and after the Indian rejection of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s assimilationist White Paper policy in 1969, Manuel went on to bring a strong Indian voice to national politics in Ottawa through the agency of the National Indian Brotherhood. He went futher. In 1975, the year after he and Michael Posluns had co-authored The Fourth World: An Indian Reality, Manuel went on the found the World Council of Indigenous Peoples (WCIP).

With the concept of the Fourth World and with the founding of the WCIP Manuel expressed the aspirations of Indigenous peoples in North Americas at a time when the movement for decolonization was changing the political landscape of global geopolitics. This effort to frame the place of Indigenous peoples in the framework of international relations was not entirely novel. For instance the Cayuga diplomat Deskahe, also known as Levi General, proved to be quite effective in bringing attention to the grievances of Six Nations Longhouse peoples to the attention of the League of Nations in Geneva after the First World War. Both Manuel and Deskahe were significant contributors to the trajectory of thought and action that led to the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by the United Nations in 2007.

Manuel’s idea of the Fourth World proved to give voice to the broader ideals of the Non-Aligned Movement that still exists to this day. The member states of the Non-Aligned Movement are former colonies of the European powers. The Non-Aligned Movement was founded at Bandung Indonesia in 1955 with a determination that those emerging from one form of colonization should eschew getting caught up in the new colonialism of superpower rivalry. As Manuel saw it, the Indigenous peoples of North America, like other colonized groups throughout the world, should avoid being mired in a false dichotomy of socialism versus capitalism, the Soviet-led world versus the US-led world. They should go beyond the clichés of the Third World to embrace their Aboriginal heritages as sources of inspiration on how to develop their diverse political economies. The embrace of genuine self-determination requires this mixture of tradition and innovation which is the essence of the Fourth World.

Manuel’s philosophical and political breakthroughs coincided with a big breakthrough in the application of the principles of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 to the land and waters of BC. As lawyer for the Nisga’s people of the Nass River Valley in northwest BC, Thomas Berger was instrumental in eliciting from the Supreme Court of Canada a rather ambivalent ruling that the idea of Indian title or Aboriginal title is a genuine feature of Canadian law. This juridical recognition had immediate implications for the progress of a major hydroelectric project in northern Quebec. In 1975 Aboriginal obstacles to this project were eased aside with the negotiation of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Treaty with the indigenous Cree population.

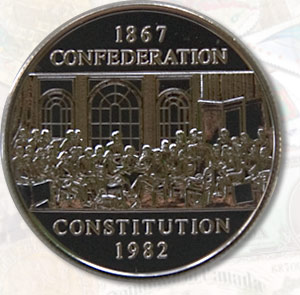

“A Great National Question:” Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canadian Federalism

It was not until the confrontations during the Indian summer of 1990 that the negotiation of Crown-Aboriginal treaties in British Columbia really began in earnest. A major factor in creating the constitutional context of these negotiations was patriation of the Canadian constitution from Great Britain in 1982. The Constitution Act 1982 emerged from intense negotiations between the federal government of Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau and the political leadership of 9 of 10 Canadian provinces. The government of Quebec under premier Rene Levesque was excluded from the negotiations because of its separatist ideology. To this day the National Assembly of Quebec has not sanctioned the Constitution Act, 1982.

It was not until the confrontations during the Indian summer of 1990 that the negotiation of Crown-Aboriginal treaties in British Columbia really began in earnest. A major factor in creating the constitutional context of these negotiations was patriation of the Canadian constitution from Great Britain in 1982. The Constitution Act 1982 emerged from intense negotiations between the federal government of Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau and the political leadership of 9 of 10 Canadian provinces. The government of Quebec under premier Rene Levesque was excluded from the negotiations because of its separatist ideology. To this day the National Assembly of Quebec has not sanctioned the Constitution Act, 1982.

The course of the negotiations in 1981 brings to light some of the key dynamics in the relationship of Aboriginal peoples to Canadian federalism. On the eve of November 5, 1981 the Canadian provincial premiers involved in the constitutional negotiations demanded the removal of the phrase in the draft text calling for the recognition and affirmation of Aboriginal and treaty rights. The federal government gave into this demand. This the federal government should not have done because it is the primary trustee charged to protect the rights, interests and titles of those Aboriginal peoples who lack their own direct representation in the constitutional process. Only a huge outpouring of protest and consternation forced the first ministers of Canada to put back the phrase in question as section 35. The word “existing”was inserted before the term, Aboriginal and treaty rights.

Why did the premiers of the English-speaking provinces make this demand? In Canada provincial governments have fought hard for an interpretation of the Constitution Act, 1867 that supports the contention that provincial governments can possess, control and monopolize Crown title to the natural resources within provincial borders. The very idea of Aboriginal and treaty rights puts limitations on provincial claims of ownership and control of natural resources. Not only that, but because “Indians and lands reserved for the Indians” were made the legislative domain of the Canadian parliament in section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867, any affirmation of Aboriginal and treaty rights carries the threat of federal intervention into what provincial authorities would like to believe is their own exclusive jurisdictional domain.

The legal meaning of the phrase, “lands reserved for the Indians,” was made the subject of a major constitutional contention between the governments of Ontario and Canada in a case known as St. Catherine’s Milling and Lumber versus the Queen.This litigious showdown, that would help define the shape of Canadian federalism, went before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) in Great Britain in 1888. At that time the JCPC was the highest court in the British Empire. Where the lawyers for the Dominion government argued for a broad interpretation of the meaning of “lands reserved for the Indians,” lawyers for Ontario argued for as narrow an interpretation as possible. The provincialist case depended on chains of precedents going back to the Crusades. Ontario’s case depended on the principle that the claims of a Christian monarch always preempt the titles of non-Christians and that the doctrine of “discovery” forms a valid basis for claiming territory.

Unfortunately the government of Ontario won the case and as a consequence provincial governments claim ownership and control over most of the natural resource wealth in Canada. The provincial effort to remove the positive affirmation of Aboriginal and treaty rights from the patriation deal in 1981 exposes the extent of the anti-Aboriginal bias of provincial authorities in Canadian federalism. Premier Don Getty of Alberta gave renewed evidenced of this anti-Aboriginal bias in 1987 after a First Ministers conference in Ottawa on Aboriginal matters. It was reported

“Getty said the recent First Ministers meeting on aboriginal rights is a perfect example of the constitutional unfairness that could drive Alberta to consider separation. The premier said if Alberta had been forced to accept entrenchment of native rights in the Constitution, separatism would have been seriously considered. “We would have gone home and talked about maybe having to pull out of the bloody country.”(Edmonton Sun, 2 June, 1987)

This history of Aboriginal and treaty rights in Canadian federalism raises one of the anomalies that discredits the federal-provincial criminalization of Kwitsel Tatel for possessing fish she harvested from the Fraser River. The prosecutor who has spent almost a decade busily criminalizing Kwitsel Tatel represents the federal Crown. The judge before whom the prosecutor presents the federal case against Kwitsel Tatel and other Aboriginal fishers is appointed by the provincial government. Would it have made sense if a state-appointed judge had evaluated the federal defense of Aboriginal treaty rights in the case of USA versus Washington state.

This subordination in British Columbia of federal authority to the power of provincial adjudication turns on its head the fiduciary responsibilities of the Crown that should fall primarily on the national government. Indeed, Aboriginal peoples have every right to be insulted by an arrangement that makes the extent of their Aboriginal rights to fish the business of a provincial system of jurisprudence in a domain of where provinces lack jurisdiction. In Canadian federalism responsibility for fish and Indians lie at the federal level. The structure of the court administering Kwitsel Tatel’s case predetermines that Aboriginal fishing is a matter for the federal criminal law administered by provincial governments.

This subordination in British Columbia of federal authority to the power of provincial adjudication turns on its head the fiduciary responsibilities of the Crown that should fall primarily on the national government. Indeed, Aboriginal peoples have every right to be insulted by an arrangement that makes the extent of their Aboriginal rights to fish the business of a provincial system of jurisprudence in a domain of where provinces lack jurisdiction. In Canadian federalism responsibility for fish and Indians lie at the federal level. The structure of the court administering Kwitsel Tatel’s case predetermines that Aboriginal fishing is a matter for the federal criminal law administered by provincial governments.

The provincialist orientation of this court institutionalizes the denial and negation of the principle that Aboriginal Affairs are matters of national significance that combine the Crown’s fiduciary responsibilities to its former Aboriginal wards, with the necessary juridical arbitration of section 35, with the explicit federal responsibility for both fish as well as for Indians and lands [and waters] reserved for the Indians. As David Laird put it in 1874 when on behalf of the federal Crown he tried to prevail on the BC’s provincial government to come to terms with the constitutional legacy of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the BC title issue forms the basis of “a great national question.” (Hall Earth into Property, 420)

Some Constitutional Questions

In 1982 the legacy of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 was renewed with the constitutionalization of the phrase, “existing Aboriginal and treaty rights.” This section 35 term has yet to be adequately defined either through the process of constitutional amendment or judicial interpretation. I think it a good constitutional question to ask the Supreme Court of Canada for some guidance on precisely who is supposed to do this recognizing and affirming of existing Aboriginal and treaty rights. Are there any legal consequences when a government, a police force, a corporation, or an individual move to deny and negate rather than recognize and affirm the existence of Aboriginal and treaty rights?

What is the responsibility of Crown officials when it comes to the implementation of section 35? What are the constraints, if any, on federal prosecutors who seem to take it as their task to deny and negate Aboriginal rights by criminalizing those in British Columbia who claim to be exercising their Aboriginal rights through the continuation of their Aboriginal fisheries. Why is it that the federal government in Canada has never, so as far I know, taken on a case that conforms to the statement in the Canadian constitution that existing Aboriginal rights are to be recognized and affirmed? Why has not the government of Canada followed the example of the federal authority in the United States in the case of USA versus Washington state?

Is there legitimacy in an approach to law that uses criminal courts and the devastating consequences of criminalization supposedly as a way to recognize and affirm an important genre of human rights? Isn’t there a fundamental contradiction in such an approach to determining the scope and limitations of section 35? The other side of determining the scope and limits of section 35 is to determine the scope and limits of both federal and provincial jurisdiction, but especially with respect to the disposition of natural resources.

The effort to define rights by criminalizing those who attempt to exercise them demeans the Canadian state in ways that I find shameful. In my view, insult is added to injury in a process that denies resources to the would-be defenders of rights even as the Canadian state retains virtually unlimited access to public resources in its quest to circumscribe Aboriginal and treaty rights as much as possible. This disparity of means negates the possibility of a level playing field. Surely Canadians can do much much better in addressing the oldest human rights issue of the Americas.

Anthony Hall is a Professor of Globalization Studies at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta Canada where he has taught for 25 years. Along with Kevin Barrett, Tony is co-host of False Flag Weekly News at No Lies Radio Network. Prof. Hall is also Editor In Chief of the American Herald Tribune. His recent books include The American Empire and the Fourth World as well as Earth into Property: Colonization, Decolonization and Capitalism. Both are peered reviewed academic texts published by McGill-Queen’s University Press. Prof. Hall is a contributor to both books edited by Dr. Barrett on the two false flag shootings in Paris in 2015.

Part II was selected by The Independent in the UK as one of the best books of 2010. The journal of the American Library Association called Earth into Property “a scholarly tour de force.”

One of the book’s features is to set 9/11 and the 9/11 Wars in the context of global history since 1492.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy