…by Jonas E. Alexis

Premillennialist George Eldon Ladd says, “The basic watershed between a dispensational and a nondispensational theology” is that dispensationalism “forms its eschatology by a literal interpretation of the Old Testament and then fits the New Testament into it. A nondispensational eschatology forms its theology from the explicit teaching of the New Testament.”[1]

For a dispensationalist or a Judaizer, many of the teachings in the Old Testament must take precedence over the teachings in New Testament—and sometimes even the teachings of Christ.

Moreover, Judaizers tend to invoke passages in the Old Testament in order to further their political and ideological ends. This has been one of the central issues among evangelical politicians.

In 2010, former presidential candidate Michele Bachmann, who has long been a supporter of Israel,[2] made the pronouncement on the eve of her political stardom that America would cease to exist if it stops supporting Israel. She said:

“I am convinced in my heart and in my mind that if the United States fails to stand with Israel, that is the end of the United States. We have to show that we are inextricably entwined, that as a nation we have been blessed because of our relationship with Israel, and if we reject Israel, then there is a curse that comes into play.

“And my husband and I are both Christians, and we believe very strongly the verse from Genesis [Genesis 12:3], we believe very strongly that nations also receive blessings as they bless Israel. It is a strong and beautiful principle.”[3]

We will not go into extensive theological exegesis here. We shall do so later in subsequent articles. But for Bachmann and others, this issue discussed in Genesis still applies to modern Israel, even though many Protestant writers have shown that God fulfilled those promises during the time of Joshua.[4] Scripture also makes it plain that all the nations have been blessed because of Jesus Christ, who is the seed of Abraham.

“For Moses truly said unto the fathers, A prophet shall the Lord your God raise up unto you of your brethren, like unto me; him shall ye hear in all things whatsoever he shall say unto you. And it shall come to pass, that every soul, which will not hear that prophet, shall be destroyed from among the people. Yea, and all the prophets from Samuel and those after, as many as have spoken, have likewise foretold of these days.

“Ye are the children of the prophets, and of the covenant which God made with our fathers, saying unto Abraham, and in thy seed shall all the kindred of the earth be blessed. Unto you first, God, having raised up his Son Jesus, sent him to bless you, in turning away every one of you from his iniquities” (Acts 3:22-26).

This is completely antithetical to the Christian Zionist movement, which to a large extent elevates geopolitical Israel above anything else, including the church. One of the leading dispensationalists to espouse such a view is Herman Hoyt, who declared that in the dispensationalist millennium, the living Israel “will be the head over all the nations of the earth” and “on the lowest level there are the saved, living, Gentile nations.”[5]

This view has been stated in many ways by other leading dispensationalist writers, including Charles C. Ryrie, J. Dwight Pentecost, H. Wayne House, Thomas D. Ice, John F. Walvoord, Arnold G. Fruchtenbaum, Hal Lindsey, and even the late Dave Hunt.[6]

Hunt goes so far as to say that “national Israel [will be] restored to its place of supremacy over the nations.”[7] For dispensationalists, geopolitical Israel is one of the keys to the millennium. Pentecost states, “The Gentiles will be Israel’s servants” during that era.[8] For Fruchtenbaum, “In the millennium Israel as a nation will rule over the Gentiles.”[9]

The only way dispensational premillennialists are able to solve this theological numbo-jumbo is to propose that God has two distinct plans: one for the church and one for the nation of Israel. Charles C. Ryrie put it this way:

“A dispensationalist keeps Israel and the church distinct.”[10]

Quoting another authority, Ryrie declares that “the basic premise of Dispensationalism is two purposes God expressed in the formation of two peoples who maintain their distinction throughout eternity.”[11]

This view was articulated by other leading dispensationalists such as Lewis Sperry Chafer,[12] and this thesis has played a major role in the writings of people like John Nelson Darby and C. I. Scofield.[13]

By the time we reach the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Dispensational Premillennialism had already been politicized, with presidents such as Ronald Reagan and beyond politically endorsing the movement. Charles Colson, a former Nixon advisor, had a cohort of friends in the White House who would lecture U.S. officials about prophecies in the book of Ezekiel and who would telephone “premillennialist faculty members at ‘Mid-South Seminary.”[14]

Ronald Reagan was also a product of Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth and other apocalyptic frenzies. Reagan told Christian Life magazine back in 1968, “Apparently never in history have so many of the prophecies come true in such a relatively short time.”

Historian Paul Boyer declared that “The Late Great Planet Earth strengthened Reagan’s prophecy belief, and at a 1971 political dinner in Sacramento shortly after leftist coup in Libya, Reagan observer soberly:

‘That’s the sign that the day of Armageddon isn’t far off…Everything is falling into place. It can’t be too long. Ezekiel says that fire and brimstone will be rained upon the enemies of God’s people. That must mean that they’ll be destroyed by nuclear weapons.’”

Reagan also said, “You know, I turn back to your ancient prophets in the Old Testament and the signs foretelling Armageddon, and I find myself wondering if we’re the generation that’s going to see that come about. I don’t know if you’ve noted any of those prophecies lately, but believe me, they certainly describe the times we’re going through.”[15]

Former president George W. Bush tried to convince France’s then president Jacques Chirac that “biblical prophecies were being fulfilled” and specifically that “Gog and Magog are at work in the Middle East,” but Chirac decided that “France was not going to fight a war based on an American president’s interpretation of the Bible.”[16]

Like the dispensationalist camps, when the Gog and Magog apocalypse failed Bush, he turned to Baghdad as the forces of evil. As we shall see, all of this is completely compatible with the Judaizing movement which got its inception in the fifteenth century.

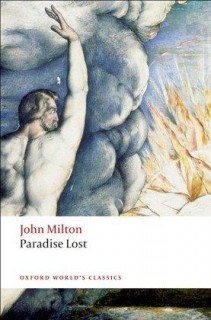

John Milton Was a Judaizer

A somewhat classic example of invoking the Old Testament to further ideological purposes is found in the life of John Milton, famed seventeenth-century English poet known for writing Paradise Lost.

Milton wanted to divorce his wife, but there was clear teaching about divorce in the New Testament. Christ taught that one ought not to divorce unless one partner has committed fornication (Matthew 5:32). Milton solved that problem by appealing to Moses and rejecting Christ’s teachings! To Milton,

“Our savior’s words touching divorce are, as it were, congealed into a stony rigour, inconsistent both with his doctrine and his office.”[17]

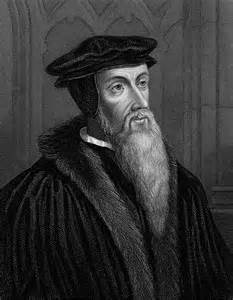

As we shall see in subsequent articles, this form of eisegesis is consistent with many Protestant writers long before Milton came on the scene. Martin Luther for example wanted to burn the book of James because James did line up with Luther’s sola fide. And John Calvin was exegetically shown to be a Judaizer on many aspects.[18]

As we shall see in subsequent articles, this form of eisegesis is consistent with many Protestant writers long before Milton came on the scene. Martin Luther for example wanted to burn the book of James because James did line up with Luther’s sola fide. And John Calvin was exegetically shown to be a Judaizer on many aspects.[18]

Milton later said,

“Yea, God himself commands in his law more than once, and by his prophet Malachi, as Calvin and the best translations read that ‘he who hates, let him divorce—that is, he who hates cannot love. Hence it is that the rabbins, and Maimonides…tells us that ‘divorce was permitted by Moses to preserve peace in marriage and quiet in the family.’”[19]

Milton’s reliance on rabbis such as Maimonides had nothing to do with the teachings of Christ, but rather with his own desire for divorce. He later published his own tract entitled The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce, in which he essentially pleaded with England to allow divorce in society based on the teachings of the Old Testament and “some of the best among reformed writers.”[20]

Yet Milton completely missed Moses’ point for sanctioning divorce in the Old Testament. As E. Michael Jones puts it,

“Milton again needs to contradict Christ and scripture, because Christ said ‘in the beginning it was not so,’ meaning that divorce was something added after the fall because Moses had to deal with the hardness of his people’s hearts.”[21]

The temptation to reject the plain teachings of Christ—and the message of things like love, truth, dignity, love for one’s neighbor, and protection the innocent—and to embrace some of the Old Testament laws that were fulfilled or nullified by the coming of Jesus Christ did not start or die out in the seventeenth century. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries many heretical movements drew their conclusions from the Old Testament.[22]

Our time is no exception. For example, Sarah Palin frequently invoked passages in the Old Testament to pursue her political ends.[23] Michelle Bachmann did the same thing in 2011. When Bachmann was obviously outmatched and losing support in Iowa, she didn’t invoke Christ or figures in the New Testament, but turned to Old Testament figures.[24]

The simple fact is that many politicians—most specifically Christian Judaizers—have over the centuries appealed to the Old Testament in order to marshal their ideological purposes.[25]

Take for example the Hussite revolution (which began in 1419), which used Moses and the nullified laws of the Old Testament, with respect to killing and pillaging enemies, as justification. There were indeed theological disputations around that time, and theological disputations got into politics, and politics got into a bloody war.[26]

The selling of indulgences was one of the doctrines that caught the spirit of that era. Luther rose up and challenged that idea. But Luther did not stop there. Luther clung to the sword as portrayed in the Old Testament. Luther used language like the Old Testament, language which can be found throughout his denunciation of the pope.

“Hearest thou this, O pope,” he wrote in 1520, “not most holy, but most sinful? O that God from heaven would soon destroy thy throne and sink it in the abyss of hell!…O Christ, my Lord, look down, let the day of thy judgment break, and destroy the devil’s nest at Rome.”[27] Luther sounded like James and John in the New Testament:

“And it came to pass, when the time was come that he [Jesus] should be received up, he stedfastly set his face to go to Jerusalem. And sent messengers before his face: and they went, and entered into a village of the Samaritans, to make ready for him. And they did not receive him, because his face was as though he would go to Jerusalem.

“And when his disciples James and John saw this, they said, Lord, wilt thou that we command fire to come down from heaven, and consume them, even as Elias did? But he turned, and rebuked them, and said, Ye know not what manner of spirit ye are of. For the Son of man is not come to destroy men’s lives, but to save them (Luke 9:52-54).

The Hussites solved problems such as indulgences by not only appealing to Moses in bearing swords and marching to crush their enemies, but also by leading mobs into churches and smearing excrement on crucifixes.[28]

Historian Howard Kaminsky declares that Huss did not decide to start the violent revolution and the radical Hussites did not draw their radical movement which led to violent acts against monks in particular from Huss himself.[29] There might be a glimpse of truth in this. But Huss’ heavy reliance on the Old Testament makes his doctrine ambiguous. He said:

“The time has come for us, just as it did for Moses in the Old Testament, to take up our swords and defend the law of God.”[30]

The obvious question is why didn’t Huss appeal to Christ, the humble servant and the model for all Christians? Why didn’t Huss appeal to passages such as Matthew 5:43-48, which implicitly forbids serious followers of Christ to take up arms against enemies, most specifically when it comes to theological disputes?

As Jones rightly argues, whether Huss liked it or not, his statement here was an obvious appeal to the Old Testament, which Huss’s followers took to a radical height. Moreover, it makes the Protestant motto sola scriptura meaningless, because if Scripture is going to be interpreted in light of the wars and pillaging of Old Testament and not in light of Christ’s teachings, then we are in deep trouble.

Historians agree that this posed a problem for the Reformers. Even Erasmus saw that Judaica expositio—a literal interpretation of many of the Old Testament principles, such as eye for an eye and tooth for a tooth, with little regard for the teachings of the New Testament—could be a problem for the Judaizers.[31]

Erasmus was proved right, for we know that “the philological works most frequently consulted by Christian Hebraists (such as Reuchlin’s De rudimentibus) were actually written by Jews. In addition, several important exegetical works of the early Reformation period—such as Bucer’s commentary on the Psalter (1529)—drew heavily upon medieval rabbinical sources, such as David Kimhi and Abraham Ibn Ezra and Solomon ben Isaac (Rashi) of Troyes.”[32]

Will Durant writes that “Luther’s conception of God was Judaic. He could speak with eloquence of the divine mercy and grace, but more basic in him was the old picture of God as the avenger, and therefore of Christ as the final judge.”[33]

Before Luther, continues Durant, judaizing rarely happened in Western culture; after Luther, “the Judaic contribution triumphed over the Greek; the Prophets won against the Aristotle of the Scholastics and the Plato of the humanists…the Old Testament overshadowed the New; Yahweh darkened the face of Christ.”[34]

This played an influential role in Luther’s writings and teachings. And this essential point has been overlooked by many Protestant writers after Luther and beyond.

It is therefore safe to say that many during the Protestant Reformation were Judaizers, though Zwingli, on a theoretical level, was probably not one of them.[35] Yet on a practical level Zwingli was a Judaizer and was even accused of betraying the Protestant motto, sola scriptura.[36]

A propaganda manifesto was written in 1412 which reads,

“And so, dear holy community in Bohemia, let us stand in battle line with our head, Master Huss, and our leader, Master Jerome; and whoever will be a Christian, let him turn to us. Let everyone gird on his sword, let brother not spare brother, nor father spare son, nor son father, nor neighbor spare neighbor…All should kill so that we can make our hands holy in the blood of the accursed ones, as Moses shows us in his books; for what is written there is an example to us.”[37]

Will Durant declared, “On July 30, 1419, a Hussite crowd paraded into New Town, forced its way into the council chamber, and threw councilors out of the windows into the street, where another crowd finished them off. A popular assembly was organized, which elected Hussite councilors.”[38]

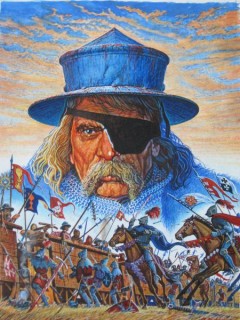

Pope Martin V organized a crusade against the Hussites, with king Sigismund approving it. The Hussites struck back by organizing their own army with Jan Zizka as the leader, “a sixty-year-old knight with one eye, who trained them, and led them to incredible victories.”[39]

Zizka defeated Sigismund, then began to espouse the view that there should be no religious dissent. As a consequence of this worldview, his army

“passed up and down Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia like a devastating storm, pillaging monasteries, massacring monks, and compelling the population to accept the Four Articles of Prague. The Germans in Bohemia, who wished to remain Catholic, became the favorite victims of Hussite arms.”[40]

The Four Articles of Prague declared that one ought to have freedom to worhip, to give no secular power to the clergy, and to punish mortal sins, yet the Hussites in general violated those principles. In other words, the document was a smokescreen for the Hussites. (However, not all Hussites were revolutionaries. There were many who were peaceful, detested wars and hatred against enemies, and practiced a return to traditional, mere, Christianity.[41])

Martin Luther was an admirer of Huss and believed he should not have been burned at the stake.[42] Later, Luther argued that “the German Church should be reconciled with the Hussites of Bohemia.”[43]

It should be made clear at the outset that there were several problems with the Reformation, but the issues were not as black and white as some historians have argued.

Calvin for example was responsible for the death of Michael Servetus, a Spanish physician who, upon reading rabbinical criticism of Christianity, no longer thought that the Trinity was valid. Servetus propounded heretical views in believing that Jesus was not co-equal with the Father, and that God the Father had to breath the Logos into Jesus. These views, among others, certainly made him a heretic, and he was disliked by both Catholics and Protestants.[44]

After writing Christianismi Restitutio in 1546, in which he denounced the idea that God had predestined some to hell and others to heaven, Servetus sent the manuscript to Calvin. Calvin returned the favor by sending Servetus a copy of his Institutes of the Christian Religion. The die was cast.

Servetus sent Institutes back to Calvin with insulting comments because he thought Calvin was making elementary errors. Servetus made the point that it was irrational for God to send some to hell irrespective of whether they want to accept him or not and then condemn those same people for not accepting him. Calvin himself wrote in his Institutes:

“By predestination we mean the eternal decree of God, by which He determined with Himself whatever He wished to happen with regard to every man. All are not created on equal terms, but some are preordained to eternal life, others to eternal damnation; and, accordingly, as each has been created for one or other of those ends, we say that he has been predestined to life or death.”[45]

In other words, freewill and predestination, in the Calvinist reading of things, are mutually exclusive. Moreover, those who are predestined to death are rebel sinners and therefore deserve God’s wrath! For example, you blindfold a person and then tell him to choose either right or left. And when he doesn’t choose what you want, you strike him dead. How is that logical?

Well, in the Calvinist reading of things, this is called compatibilism. It is the metaphysical idea that people are responsible and even blamed for their actions even though they cannot possibly do otherwise, even though it was God’s intention and decree that they fall into temptation and therefore be condemned!

These are essential in Calvin’s doctrine of predestination, and this is the doctrine that has been repudiated by many because it is pregnant with internal contradictions and because it makes God the author and the actual creator of sin. Listen to one Calvinist: God “can’t sin.” But two sentences later, the same author declares that God “created sin.”[46] The Reformed author did not appeal to sola scriptura this time to propound that doctrine but appeals to the Westminster Confession in order to support his case.[47]

By propounding this doctrine in his Institutes, Calvin made Servetus’ job easy.

Later Calvinists have found this doctrine repugnant and soon the essential doctrine of predestination as propounded by Calvin in his Institutes was “predestined” to split into five groups: five points, four points, three points, two points, and one point.

Servetus also implicitly made the point that if God condemns some for not responding to his gift of salvation, then the obvious conclusion is that God had given them the ability to respond to his calling. Modern Calvinists have struggled mightily to solve that contradiction.[48]

Calvin, in return, wrote to one of his friends in 1546,

“Servetus has just sent me a long volume of his ravings. If I consent he will come here, but I will not give my word, for should he come, if my authority is of any avail, I will not suffer him to get out alive.”[49]

By this time, Servetus was wanted by both Protestants and Catholics for heresy. He was arrested in Catholic lands, but barely escaped from prison and settled in Protestant Geneva, Calvin’s territory. On a Sunday, he went to church and was quickly recognized. Calvin quickly ordered his arrest.

During the trial, he was partially accused of having “in the person of M. Calvin, defamed the doctrines of the Gospel of the Church of Geneva.”[50] On two occasions, Calvin appeared during the trial as Servetus’s accuser, though “the Protestant Council of Geneva asked the Catholic judges at Vienne for particulars of the charges that had been brought against Servetus.”[51]

During the trial, Servetus literally begged for mercy, and two opponents of Calvin were summoned to save Servetus from burning at the stake. When the ministers declared that Servetus should be punished for his “utter lack of the spirit of meekness and docility,” he responded by saying, “You should show it toward me even though I were possessed of an evil spirit.”[52]

Durant declared that the two opponents irritated Calvin even more than Servetus. Matteo Gribaldi, a professor of jurisprudence at Padua, called upon the people at the assembly to seriously reconsider the fraudulent civil punishment for religious opinions and matters. He was banished “on suspicion of Unitarianism.”

Gribaldi was later established as a professor of law at the University of Tubingen, but “Calvin sent word there of Gribaldi’s doubts; the university pressed him to sign a Trinitarian confession; instead he fled to Bern, where he died of the plague in 1564.”[53]

Servetus moved on to write a reply to Calvin, in which he called Calvin “liar,” “impostor,” “hypocrite,” and “miserable wretch.” Calvin returned the favor by calling Servetus a “dirty dog” who “wiped his snout” and the “perfidious scamp.”[54] Bainton declares that Servetus’s statement that Calvin was a “liar” was not entirely without merit. For example, Calvin, during the trial, accused Servetus of being unable to understand and read Greek, when in fact Servetus knew the language well.[55]

Servetus was eventually condemned to be executed. Scared to death, Servetus begged Calvin to reconsider. Calvin declared that he would have a second thought if Servetus recanted from his heretical views. Servetus refused. He was eventually burned alive on October 27, 1553.[56]

“When the executioner brought the fire before his face he gave such a shriek that all the people were horror-stricken. As he lingered, some threw on wood. In a fearful wail he cried, ‘O Jesus, Son of the Eternal God, have pity on me!’”[57]

Many Protestant reformers were in agreement that Servetus deserved his punishment. Philip Melanchthon, a collaborator of Martin Luther, wrote a letter to Calvin and others giving “thanks to the Son of God” for the “punishment of this blasphemous man,” and declared that the burning was “a pious and memorable example to all posterity.”[58]

Some Protestant scholars such as Alister McGrath have tried to downplay Calvin’s role in the execution, thereby giving the impression that Calvin had nothing to do with it. Yet the evidence against such a defense is found in Calvin’s own mouth.

McGrath declares that Calvin’s “tacit support for the capital penalty for offenses such as heresy which he (and his contemporaries) regarded as serious makes him a little more than a child of his age, rather than an outrageous exception to its standards…To single out Calvin for particular criticism, however, suggests a selectivity approaching victimization.”[59]

McGrath says that Calvin’s involvement in the affair “was oblique.” Yet Calvin himself declared the opposite. McGrath continues, “The trial, condemnation and execution of Servetus were entirely the work of the city council, at a period in its history when it was particularly hostile to Calvin. The Perrinists had recently gained power, and were determined to weaken his position.”[60]

Not so. Even other Protestant historians such as Roland H. Bainton agreed that the whole trial was orchestrated by John Calvin.[61] Moreover, Calvin told us,

“And what crime was it of mine if our Council at my exhortation…took vengeance upon his execrable blasphemies?”[62]

McGrath declares, “Calvin himself attempted to alter the mode of execution to the more humane beheading; he was ignored.”[63] McGrath never tells us that it was Servetus who wanted “the more humane beheading,” to which Calvin agreed. The request was denied by the council, but Calvin had a hand in how Servetus was executed.

Calvin himself wrote a letter to the King of Navarre years later when he was still receiving criticism for his involvement in the execution, saying,

“Do not fail to rid the country of those zealous scoundrels who stir up the people to revolt against us. Such monsters should be exterminated, as I have exterminated Michael Servetus the Spaniard.”[64]

In a rather sophisticated way of downplaying Calvin’s influence in the affair, McGrath declares, “Every major Christian body which traces its history back to the sixteenth century has blood liberally scattered over its credentials. Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed and Anglican: all have condemned and executed their Servetuses, whether directly, or—as in the case of Calvin himself—indirectly.”[65]

Calvin received widespread criticism for his act, prompting him in 1554 to write Defensio Orthodoxae Fidei de Sacra Trinitate Contra Prodigiosos Errores Michaelis Serveti, in which he quoted passages in the Old Testament such as Deuteronomy 13:5-15, 17:2, Exodus 22:20, and Leviticus 24:16 to buttress his defense of burning heretics.

“Whoever shall maintain that wrong is done to heretics and blasphemers in punishing them makes himself an accomplice in their crime…Wherefore does He [God] demand of us so extreme severity if not to show us that due honor is not paid Him so long as we set not His service above every human consideration, so that we spare not kin nor blood of any, and forget all humanity when the matter is to combat for his glory?”[66]

By this time Calvin was already a Judaizer in applying Old Testament law to heretics. Even Durant wrote, “Whereas in general [Calvin] accepted St. Paul as his guide, he refused to use the Pauline expedient of declaring the old law superseded by the new.”[67]

E. Michael Jones agrees with Louis Israel Newman that Calvin knew the consequences of not burning Servetus, that he was soon going to be accused of Judaizing.[68] Diarmaid MacCulloch declares that for political reasons, Calvin wanted to prove to his enemies that he was not weak.[69]

But by burning Servetus, Calvin implicitly ended up Judaizing anyway. This was so clear that Calvin almost applied the same Old Testament law to a close friend of his, Sebastian Castellio.

Castellio was born in France in 1515 and became erudite in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and was a Greek teacher at Lyons. He also lived with Calvin for a while and, in 1541, Calvin appointed him as rector of the Latin School at Geneva.

In time, Castellio parted company with Calvin on the doctrine of predestination and accused Calvin of intolerance, among other things, though he still admired Calvin as a friend.

Unlike Servetus, who told Calvin that Simon Magus was the real father of the doctrine of predestination,[70] Castellio never castigated Calvin as a liar. Calvin again summoned the Council and accused Castellio. He was banished and for nine years lived in abject poverty, “supporting a large family, and working at night on his version of the Scriptures. He finished this in 1551.”[71]

Castellio finally got to teach Greek again at the University of Basel, and was completely shocked that Calvin was the main culprit behind the execution of Servetus. Years later, Castellio produced Haereticis an Sint Persequendi (Should Heretics Be Persecuted?), in which he implied that Christ would not have burned anyone alive for being a heretic.

In order to make a rational and exegetical case, Castellio appealed to the New Testament and declared that the Old Testament laws with respect to burning heretics were out-dated.

Moreover, according to Castellio, execution, or martyrdom, is a bad way to stop an idea. The best way to silence a false belief is through rational discourse and exegetical argument. Calvin indirectly counter-attacked through his friend Theodore de Besze.

In his De Haereticis a Civili Magistratu Puniendis Libellus (A Little Book on the Duty of Civil Magistrates to Punish Heretics), Besze argued that the Old Testament still stands. Castellio responded, but his manuscript was not published until half a century later, probably for fear that his death would be imminent if he did.

In 1563, Castellio died in poverty, and “Calvin pronounced his early death a just judgment of a just God.”[72] In 1553, Calvin wanted to widen his support, which infuriated some opponents and ended up into open confrontation.

“Four of his chief opponents who did not flee the city were beheaded, and their defeat, Calvin’s triumph, was represented as God’s triumph.”[73]

As we are beginning to see, the Judaizing spirit, which got its inception in the fifteenth century, is very complicated. The modern Christian Zionist movement, which got its theological metaphysics in the Judaizing spirit, is another Jewish movement with some “Christian” flavor. At least four more articles on this topic are on their way.

Jonas E. Alexis has degrees in mathematics and philosophy. He studied education at the graduate level. His main interests include U.S. foreign policy, the history of the Israel/Palestine conflict, and the history of ideas. He is the author of the new book Zionism vs. the West: How Talmudic Ideology is Undermining Western Culture. He teaches mathematics in South Korea.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy