“And don’t you think that being deceived about the truth is a bad thing, while having a grasp of the truth is good? And don’t you think that having a grasp of the truth is having a belief that matches the way things are?” Plato[1]

…by Jonas E. Alexis

Whenever I want to be entertained, I sometimes sit back and observe some of the internal contradictions that exist in the political and intellectual landscape. Sometimes it would get so bad that I would end up asking myself,

Whenever I want to be entertained, I sometimes sit back and observe some of the internal contradictions that exist in the political and intellectual landscape. Sometimes it would get so bad that I would end up asking myself,

“Why did those people even bother to take a simple course in geometry or logic in high school or college if they cannot (or will not) apply it to real-life? Why do people want to get an education after all?

How can those people not see the logical or metaphysical implications of their own positions? Is it really that hard to sit down and start examining the logical endpoint of one’s own position? Do those people really care about truth and logic and consistency at all? Or do they just want to insult logic and reason?”

People who take logic and reason seriously always try to follow an argument to its logical conclusion and see where it really leads.

For example, it is hard to be a completely consistent atheist precisely because somehow you are going to end up living in contradiction, most specifically when it comes to morality. Nietzsche saw this and many other metaphysicians such as Camus and Sartre realized it. Here is a classic example.

In 1996, Richard Dawkins argued vigorously that

“The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, and no good, nothing but blind pitiless indifference…”[2]

Got that? If there is no design, then the universe has no purpose, no evil and no good. Yet ten years later, Dawkins proved that there is something called good and evil by calling the God of the Old Testament

“jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving control-freak; a vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser; a misogynistic, homophobic, racist, infanticidal, genocidal, filicidal, pestilential, megalomanical, sadomasochistic, capriciously malevolent bully.”[3]

Beautiful, isn’t it? I thought there was no good and evil? Dawkins needs to thank goodness that he never met philosophers like Emmanuel Kant.

It is the same thing when Darwinists hold that Jewish behavior is genetic and then try to hold Jews accountable for their actions. The interesting implication that follows from this principle is this: people are responsible and even blamed for their actions even thought they cannot possibly do otherwise! This goes against all our legal system.

It is the same thing when Darwinists hold that Jewish behavior is genetic and then try to hold Jews accountable for their actions. The interesting implication that follows from this principle is this: people are responsible and even blamed for their actions even thought they cannot possibly do otherwise! This goes against all our legal system.

Secondly, there is no morality according to the Darwinian evolutionary paradigm. Darwin, who I supposed was as good a Darwinian as anyone else, had this to say in the first edition of the Descent of Man: “Extinction follows chiefly from the competition of tribe with tribe, and race with race.”[4]

According to Darwin, sub-species—he called them “anthropomorphous apes”—will be eliminated by the “civilized races of man.” In other words, the “civilized races of man” will emerged out of struggle, out of cut-throat competition, and out of ruthless behavior.

Moreover, Darwinian metaphysics is, at its core, deterministic.[5] Listen to philosopher of science Michael Ruse:

“I appreciate when somebody says ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself,’ they think they are referring above and beyond themselves…Nevertheless, to a Darwinian evolutionist it can be seen that such reference is truly without foundation.

“Morality is just an aid to survival and reproduction…an ephemeral product of the evolutionary process, just as are other adaptations. It has no existence or being beyond this, and any deeper meaning is illusory.”[6]

Massimo Pilgliucci, evolutionary biologist and Chair of the Department of Philosophy at the University of New York, stated unambiguously,

“There is no such thing as objective morality. We got that straightened out. Morality in human cultures has evolved and is still evolving, and what is moral for you might not be moral for the guy next door and certainly is not moral for the guy across the ocean.”

Science fiction writer H. P. Lovecraft wrote:

“Morality is the adjustment of matter to its environment—the natural arrangement of molecules. More especially it may be considered as dealing with organic molecules.”[7]

And people like Francis Crick tell us that things like joy, love, emotion, freewill, are simply illusions.[8] In short, Darwinian metaphysics provides no serious mechanism for morality. In fact, the system works against it. But Darwinists continue to invoke morality to make their point. Once again, this is a contradiction that they cannot avoid.

These people should read G. K. Chesterton, who wrote eloquently and powerfully:

“The new rebel is a Skeptic, and will not entirely trust anything. He has no loyalty…and the fact that he doubts everything really gets in his way when he wants to denounce anything. For all denunciation implies a moral doctrine of some kind; and the modern revolutionist doubts not only the institution he denounces, but the doctrine by which he denounces it…

“As a politician, he will cry out that war is a waste of life, and then, as a philosopher, that all life is a waste of time. A Russian pessimist will denounce a policeman for killing a peasant, and then prove by the highest philosophical principles that the peasant ought to have killed himself. A man denounces marriage as a lie, and then denounces aristocratic profligates for treating it as a lie.

“He calls a flag a bauble, and then blames the oppressors of Poland or Ireland because they take away that bauble. The man of this school goes first to a political meeting, where he complains that savages are treated as if they were beasts; then he takes his hat and umbrella and goes to a scientific meeting, where he proves that they practically are beasts.

“In short, the modern revolutionist, being an infinite skeptic, is always engaged in undermining his own mines. In his book on politics he attacks men for trampling on morality; in his book on ethics he attacks morality for trampling on men. Therefore the modern man in revolt has become practically useless for all purposes of revolt. By rebelling against everything, he has lost his right to rebel against anything.”[9]

What I am quickly learning is that many people seem to devote themselves to a particular system but do not have the intellectual courage to follow that system all the way.

In the previous article, I pointed out that Patrick Slattery objected to the idea that if Jewish behavior is genetic, then David Duke should be happy that Jews are acting that way precisely because Duke is a Darwinist.

Moreover, if we grant that the idea is true, then Duke is indirectly supporting the Jewish cause because survival of the fittest, the struggle for life and existence, is a logical extension which inexorably and effortlessly flows from Darwin’s writings. Slattery wagged his finger and wished that I had not entertained thoughts like that.

But Slattery again seems to forget that Duke is a Darwinist! Once Slattery and Duke clarify this vital contradiction in a cogently rational manner, then I will stop entertaining thoughts like Duke is indirectly promoting the Jewish cause.[10]

About two years ago, I had a discussion on this issue with an eminent scholar and professor who is teaching in the state of California. I challenged him to consider the theological and philosophical aspect of the issue. His response?

“The theological perspective is not my cup of tea.”

But the professor was trying to study the real conflict that is inherent in Judaism! Suppose a person is trying to examine Christianity or Islam but does not want to examine the sayings or teachings of Christ or Muhammad. Would you say that the person is doing real research?

The professor went about explaining the issue through “genetics” and “science” and could not see how his view lacks moral clarity and intellectual depth.[11]

A contradiction can come in many forms, but for our purpose here, let us define what we mean.

A contradiction can come in many forms, but for our purpose here, let us define what we mean.

A contradiction is, put simply, this: “Nothing be said both to be and not be something at the same time and in the same respect.”[12]

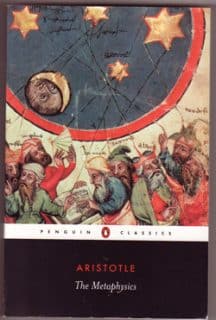

This is known as the principle of non-contradiction (or the law of non-contradiction), which was first articulated quite powerfully by Aristotle in his Metaphysics. He argued,

“It is impossible for the same thing at the same time both to be-in and not to be-in the same thing in the same respect.”[13]

Subsequent works in mathematics and philosophy have applied almost the same principle. In defining that principle, the Oxford Companion to Philosophy puts it this way: “Nothing both is and is not” at the same time and in the same respect.[14]

In other words, for two statements to be contradictory, they must say opposite things (implicit or explicit) at the same time and in the same respect. This principle is non-negotiable if one is to remain rational.

Commenting on Aristotle’s Metaphysics, the Persian polymath and Medieval philosopher Avicenna (Ibn Sina) said:

“Anyone who denies the law of non-contradiction should be beaten and burned until he admits that to be beaten is not the same as not to be beaten, and to be burned is not the same as not to be burned.”

A contradiction, as we all know, is not just a mental conflict. It too has its consequences—sometimes huge consequences. What is so frustrating is that when people cannot recognize or are not willing to see the implicit contradictions in their own statements, intelligent debates become almost impossible or mute.

I do not get angry very easily, but whenever so-called thinking people try to deliberately ignore a vital contradiction in their own worldview, that usually ticks me off in an instant. It usually happens when I am dealing with people who ought to know better. However, I have no problem when my own students cannot see their own contradictions because that can easily be fixed through clarification.

Three months ago, I told a very smart student of mine that there seems to exist an objective standard by which we can say that this or that painting is good or bad art and that real art itself seems to be transcendent. I proceeded to say that if one looks at some of the paintings by people like Michelangelo or Da Vinci, one is faced with the frightening conclusion that something good and transcendent is at work.

Three months ago, I told a very smart student of mine that there seems to exist an objective standard by which we can say that this or that painting is good or bad art and that real art itself seems to be transcendent. I proceeded to say that if one looks at some of the paintings by people like Michelangelo or Da Vinci, one is faced with the frightening conclusion that something good and transcendent is at work.

The student was a little upset because, according to him, there is no way to say that this or that art is good or bad. According to him, it is a matter of opinion. “Finally, I think I can destroy your point here,” he said. “I can prove you are absolutely wrong about this.” “Please,” I said. “I’d like to hear this.”

One afternoon, he spent about one hour trying to show me that there is no objective standard by which one can judge a piece of artwork. After he was done, I simply said:

“All right. You just spent virtually one hour trying to convince me that there is no objective standard with respect to art. Should I and everyone else accept your view?”

He said, “Which view?” “That there is no standard for analyzing art?” I responded.

Instantly he said, “Yes. Why would I be talking to you about this the whole time?” Then I started smiling, to which he replied, “What? What’s so funny?”

I responded,

“And you can’t see that this view is a standard in and of itself? You have just trapped yourself into your own cage. You are desperately trying to persuade me to accept the view that there are no standards, which means that you believe that my view is absolutely wrong. Aren’t you appealing to an implicit standard which presumably says that ‘Alexis is quite wrong? And don’t forget you said that everyone ought to accept this view.’”

He stared at me for a while and then turned to the window. After about twenty five seconds, he muttered,

“Crap. Headache.”

I proceeded to say,

“The reason you and I are having this conversation is that you are implicitly appealing to a standard, even though you explicitly deny it. And the moment you say that you are going to prove me wrong, you indirectly are proving my point.

“Furthermore, if I grant your argument here–that there are basically no standards–then my opinion is just as valid as yours, which means that it is presumptuous of you to spend almost an hour to convince me that you are right. It also implies that you are narrow-minded and cannot tolerate a different worldview.

“The moment you open your mouth and say that I am wrong, then you are ultimately saying that some interpretations are good and some interpretations are bad. If you can wrestle with that for the next two days and come back with a rigorous answer, then let us talk again.”

He never solved the dilemma precisely because you simply cannot deny esthetic standards without assuming esthetic standards. As G. K. Chesterton convincingly articulated again, “For all denunciation implies a moral doctrine of some kind.”[15]

The next time we met, he brought one of his friends, who was also interested in the discussion. We went to Dunkin’ Donuts and spent about two hours there. After we were done talking, he told his friend, “You see, I told you.”

“What did you tell him?” I said.

“I told him that if he can convince you otherwise, then I’d buy him a house,” he responded.

My last statement to them was simply this:

“I didn’t invent reason. I simply submit myself to it. The reason you and I can have a decent conversion is because we are part of reason. If you follow reason all the way, then you will be fine. And if you follow reason to its logical conclusion, as Plato and others have done, then you will ultimately have an encounter with the author or reason, who is good, transcendent, wise, and who is beyond the space-time continuum. It is up to you. My encouragement to you is to go all the way.”

[1] Plato, The Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 116.

[2] Richard Dawkins, River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life (New York: Basic Books, 1995), 133.

[3] Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (New York: Mariner Books, 2008), 51.

[4] Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1872), 229.

[5] For a study on this, see for example Hilary Rose and Steven Rose, Alas, Poor Darwin: Arguments Against Evolutionary Psychology (New York: Vintage, 2001).

[6] Michael Ruse, The Darwinian Paradigm: Essays on its History, Philosophy, and Religious Implications (New York: Routledge, 1989), 268-269.

[7] H. P. Lovecraft, “A Letter on Religion,” Christopher Hitchens, ed., The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever (New York: Da Capo Press, 2007), 135.

[8] Francis Crick, The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 33.

[9] G. K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1996), 52-53.

[10] I have no confidence that they will address the issue in a cogently rational manner. Darwin himself struggled with the idea and had to live in contradiction. For example, he thought that slavery was wrong. But he could come up with a rational answer as to why slavery was wrong precisely because his own idea implicitly supports slavery.

[11] I challenge Duke and Slattery to respond cogently and consistently. The issue is not as easy as positing an assertion and then leaving the scene without facing the consequences. In fact, the issues are much more subtle and complicated. For similar studies, see for example John Horgan, The Undiscovered Mind: How the Human Brain Defies Replication, Medication, and Explanation (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999); M. R. Bennett and P. M. S. Hacker, Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003); Maxwell Bennett and Daniel Dennett, Neuroscience and Philosophy: Brain, Mind, & Language (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007).

[12] Manuel Velasquez, Philosophy: A Text with Readings (CA: Wadsworth Group, 2002), 51.

[13] Aristotle, The Metaphysics (New York: Penguin Books, 1998), 87.

[14] Ted Honderich, The Oxford Companion to philosophy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 507; for other sources, see for example Douglas Walton, Informal Logic: A Pragmatic Approach (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008); Jacob Van Vleet, Informal Logical Fallacies (Lanham: University Press of America, 2011); T. Edward Damer, Attacking Faulty Reasoning: A Practical Guide to Fallacy-Free Arguments(Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2009); S. Morris Engel, Fallacies and Pitfalls of Language: The Language Trap (New York: Dover Publications, 1994).

[15] Chesterton, Orthodoxy, 52-53.

Jonas E. Alexis has degrees in mathematics and philosophy. He studied education at the graduate level. His main interests include U.S. foreign policy, the history of the Israel/Palestine conflict, and the history of ideas. He is the author of the new book Zionism vs. the West: How Talmudic Ideology is Undermining Western Culture. He teaches mathematics in South Korea.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy