Thomas Paine: The Forgotten Founding Father

Thomas Paine: The Forgotten Founding Father

Too Radical Yet Without Thomas Paine, there would be No America

Thomas Paine (Thetford, England, 29 January 1737 – 8 June 1809, New York City, USA) was a pamphleteer, revolutionary, radical, and intellectual. Born in Great Britain, he lived in America, having migrated to the American colonies just in time to take part in the American Revolution, mainly as the author of the powerful, widely-read pamphlet, Common Sense (1776), advocating independence for the American Colonies from the Kingdom of Great Britain. In the The American Crisis, pamphlets supporting the Revolution, he wrote the very famous lines:

"These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph."

Later, Paine was a great influence on the French Revolution. He wrote the Rights of Man (1791) as a guide to the ideas of the Enlightenment. Despite an inability to speak French, he was elected to the French National Assembly in 1792. Regarded as an ally of the Girondists, he was seen with increasing disfavour by the Montagnards and in particular by Robespierre.

Paine was arrested in Paris and imprisoned in December 1793; he was released in 1794. He became notorious with his book, The Age of Reason (1793-94), which advocated deism and took issue with Christian doctrines.

In Agrarian Justice (1795), he introduced concepts similar to socialism. Paine remained in France during the early Napoleonic Era, but condemned Napoleon's moves towards dictatorship, calling him "the completest charlatan that ever existed.". Paine remained in France until 1802, when he returned to America on an invitation from Thomas Jefferson, who had been elected president.

Paine died at 59 Grove Street in Greenwich Village, New York City, on the morning of June 8, 1809.

Born in 1737, Paine grew up around farmers and uneducated people, as his parents, Joseph Paine, a Quaker, and Frances Cocke, an Anglican, were impoverished. He left school at the age of 12 and was apprenticed to his father, a corsetmaker, at 13, but apparently failed at this. At 19, Paine became a merchant seaman, serving a short time before returning to Great Britain in April 1759. There he became a master corsetmaker and set up a shop in Sandwich, Kent. On September 27, 1759, Paine married Mary Lambert. His business collapsed soon after. His wife became pregnant, and, following a move to Margate, went into early labor and died along with her child.

In July 1761, Paine returned to Thetford where he worked as a supernumerary officer. In December 1762, he became an excise officer in Grantham, Lincolnshire. In August 1764, he was again transferred, this time to Alford, where his salary was £50 a year. On 27 August 1765, Paine was discharged from his post for claiming to have inspected goods when in fact he had only seen the documentation. On July 3, 1766, he wrote a letter to the Board of Excise asking to be reinstated. The next day the board granted his request to be filled, upon vacancy. While waiting for an opening, Paine worked as a staymaker in Diss, Norfolk and later as a servant (records show he worked for a Mr. Noble of Goodman's Fields and then for a Mr. Gardiner at Kensington). He also applied to become an ordained minister of the Church of England and, according to some accounts, he preached in Moorfields.

In 1767, Paine was appointed to a position in Grampound, Cornwall. He was subsequently asked to leave this post to await another vacancy and he became a schoolteacher in London. On 19 February 1768, Paine was appointed to Lewes, East Sussex. He moved into the room above the 15th-century Bull House, a building which held the snuff and tobacco shop of Samuel and Esther Ollive. Here Paine became involved for the first time in civic matters when Samuel Ollive introduced him into the Society of Twelve, a local elite group that met twice a year to discuss town issues. In addition, Paine participated in the Vestry, the influential church group that collected taxes and tithes and distributed them to the poor. On 26 March 1771, at age 36, he married his landlord's daughter, Elizabeth Ollive.

From 1772 to 1773, Paine joined other excise officers in lobbying Parliament for better pay and working conditions for excisemen, and in the summer of 1772 he published The Case of the Officers of Excise, a 21-page article and his first political work. Paine had 4,000 copies printed and spent the winter in London distributing the pamphlet to members of Parliament. In the spring of 1774, Paine was dismissed from the excise service for being absent from his post without permission, and his tobacco shop failed as well. On April 14, he auctioned off his household possessions to pay his debts. On June 4, he signed a separation agreement with his wife and moved to London where a friend introduced him to Benjamin Franklin in September. Franklin advised Paine to emigrate to the British colonies in America, and wrote him letters of recommendation. Paine left England in October, arriving in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on November 30, 1774.

Paine barely survived the transatlantic voyage. The drinking water on the ship was so bad that typhoid fever killed five passengers, and Paine was too ill to leave his cabin when he arrived in Philadelphia. Benjamin Franklin's physician, who had arrived to welcome him to America, literally had to pick up Paine and carry him off. It took the doctor six weeks to nurse Paine back to health.

Paine was also an inventor, receiving a patent in Europe for a single-span iron bridge, even though through a lack of funds, the bridge was in a field in Paddington, London. He developed a smokeless candle, and worked with John Fitch on the early development of steam engines. This aptitude for invention, coupled with his originality of thought, found him an advocate more than a century later in the famous inventor Thomas Edison. Edison championed Paine's achievements and helped restore him to his proper place in history.

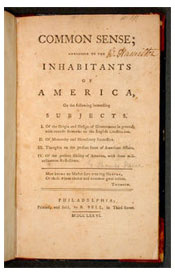

Common Sense, Paine's pro-independence monograph published anonymously on 10 January 1776, spread quickly among literate colonists. Within three months, 120,000 copies are alleged to have been distributed throughout the colonies, which themselves totaled only four million free inhabitants, making it the best-selling work in 18th-century America. Its total sales in both America and Europe reached 500,000 copies. It convinced many colonists, including George Washington and John Adams, to seek redress in political independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain, and argued strongly against any compromise short of independence. The work was greatly influenced (including in its name – Paine had originally proposed the title Plain Truth) by the equally controversial pro-independence writer Benjamin Rush and was instrumental in bringing about the Declaration of Independence.

Common Sense, Paine's pro-independence monograph published anonymously on 10 January 1776, spread quickly among literate colonists. Within three months, 120,000 copies are alleged to have been distributed throughout the colonies, which themselves totaled only four million free inhabitants, making it the best-selling work in 18th-century America. Its total sales in both America and Europe reached 500,000 copies. It convinced many colonists, including George Washington and John Adams, to seek redress in political independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain, and argued strongly against any compromise short of independence. The work was greatly influenced (including in its name – Paine had originally proposed the title Plain Truth) by the equally controversial pro-independence writer Benjamin Rush and was instrumental in bringing about the Declaration of Independence.

Loyalists attacked Common Sense with vigor. One such early attack, entitled Plain Truth, was written in 1776 by prominent loyalist James Chalmers. An expatriate of Scotland, Chalmers attacked Paine's writing as "quackery." Chalmers would serve as commander of the First Battalion of Maryland Loyalists in the war.[citation needed]

Paine's strength lay in his ability to present complex ideas in clear and concise form, as opposed to the more philosophical approaches of his Enlightenment contemporaries in Europe, and it was Paine who proposed the name United States of America for the new nation. When the war arrived, Paine published a series of important pamphlets, The Crisis, credited with inspiring the early colonists during the ordeals faced in their long struggle with the British. The first Crisis paper began with the famous words:

In 1778, Paine alluded to the then ongoing secret negotiations with France in his pamphlets, and there was a scandal which resulted in Paine being dropped from the Committee on Foreign Affairs. In 1781, however, he accompanied John Laurens during his mission to France. His services were eventually recognized by the state of New York by the granting of an estate at New Rochelle, New York, and he received considerable gifts of money from both Pennsylvania and – at Washington's suggestion – from Congress. Later, whilst in France, Thomas Paine was scathing towards Washington, writing in a letter to him, "I do not know whether you have lost your principles or that you never had any",[citation needed] when he realized that the American revolution had been hijacked by an elite, as was happening in France. He was also violently opposed to Washington owning slaves.

Returning to Europe, Paine finished his Rights of Man on 29 January 1791 whilst staying with his friend Thomas 'Clio' Rickman. On January 31, he passed the manuscript to the publisher Joseph Johnson, who intended to have it ready for Washington's birthday on February 22. Johnson was visited on a number of occasions by agents of the government. Sensing that Paine's book would be controversial, he decided not to release it on the day it was due to be published. Paine quickly began to negotiate with another publisher, J.S. Jordan. Once a deal was secured, Paine left for Paris on the advice of William Blake, leaving three good friends, William Godwin, Thomas Brand Hollis and Thomas Holcroft, in charge of concluding the publication. The book appeared on March 13, three weeks later than originally scheduled. It was an abstract political tract published in support of the French Revolution, written as a reply to Reflections on the Revolution in France by Edmund Burke. The book— which was highly critical of monarchies and European social institutions— sold briskly but was so controversial that the British government put Paine on trial in absentia for seditious libel. He later published a second edition of the Rights of Man in February 1792 which contained a plan for the reformation of England, including one of the first proposals for a progressive income tax.

Regarded as an ally of the Girondins, he was seen with increasing disfavour by the Montagnards who were now in power, and in particular by Robespierre. A decree was passed at the end of 1793 excluding foreigners from their places in the Convention (Anacharsis Cloots was also deprived of his place). Paine was arrested and imprisoned in December 1793.

Paine protested and claimed that he was a citizen of America, which was an ally of Revolutionary France, rather than of Great Britain, which was by that time at war with France. However, Gouverneur Morris, the American ambassador to France, did not press his claim, and Paine later wrote that Morris had connived at his imprisonment. Paine thought that George Washington had abandoned him, and was to quarrel with him for the rest of his life.[9]

Imprisoned and fearing that each day might be his last, Paine escaped execution apparently by chance. A guard walked through the prison placing a chalk mark on the doors of the prisoners who were due to be condemned that day. He placed one on the door of the cell that Paine shared with three other prisoners, which, due to Paine being ill at the time, he had asked to be left open. The prisoners in the cell then closed the door so that the chalk mark faced into the cell when they were due to be rounded up. They were overlooked, and survived the few vital days needed to be spared by the fall of Robespierre on 9 Thermidor (27 July 1794). Paine was released in November 1794 due in large part to the work of the new American Minister to France, James Monroe.

Prior to his arrest and imprisonment, knowing that he would likely be arrested and executed, Paine wrote the first part of The Age of Reason, an assault on organized "revealed" religion combining a compilation of inconsistencies he found in the Bible with his own advocacy of Deism. In his "Autobiographical Interlude" which is found in The Age of Reason between the first and second parts, Paine writes, "Thus far I had written on the 28th of December, 1793. In the evening I went to the Hotel Philadelphia . . . About four in the morning I was awakened by a rapping at my chamber door; when I opened it, I saw a guard and the master of the hotel with them. The guard told me they came to put me under arrestation and to demand the key of my papers. I desired them to walk in, and I would dress myself and go with them immediately."

In 1800 , Paine purportedly had a meeting with Napoleon. Napoleon claimed he slept with a copy of Rights of Man under his pillow and went so far as to say to Paine that "a statue of gold should be erected to you in every city in the universe." However, Paine quickly moved from admiration to condemnation as he saw Napoleon's moves towards dictatorship, calling him "the completest charlatan that ever existed."[10] Paine remained in France until 1802 when he returned to America on an invitation from Thomas Jefferson.

Paine returned to America in the early stages of the Second Great Awakening and a time of great political partisanship. The Age of Reason gave ample excuse for the religiously devout to hate him and the Federalists attacked him for his ideas of government stated in Common Sense, for his association with the French Revolution, and for his friendship with President Jefferson. Also still fresh in the minds of the public was his Letter to Washington, published six years prior to his return.

Paine died at the age of 72, at 59 Grove Street in Greenwich Village, New York City on the morning of June 8, 1809. Although the original building is no longer there, the present building has a plaque noting that Paine died at this location. At the time of his death, most American newspapers reprinted the obituary notice from the New York Citizen, which read in part: "He had lived long, did some good and much harm." Only six mourners came to his funeral, two of whom were black, most likely freedmen. The great orator and writer Robert G. Ingersoll wrote:

"Thomas Paine had passed the legendary limit of life. One by one most of his old friends and acquaintances had deserted him. Maligned on every side, execrated, shunned and abhorred — his virtues denounced as vices — his services forgotten — his character blackened, he preserved the poise and balance of his soul. He was a victim of the people, but his convictions remained unshaken. He was still a soldier in the army of freedom, and still tried to enlighten and civilize those who were impatiently waiting for his death, Even those who loved their enemies hated him, their friend — the friend of the whole world — with all their hearts. On the 8th of June, 1809, death came — Death, almost his only friend. At his funeral no pomp, no pageantry, no civic procession, no military display. In a carriage, a woman and her son who had lived on the bounty of the dead — on horseback, a Quaker, the humanity of whose heart dominated the creed of his head — and, following on foot, two negroes filled with gratitude — constituted the funeral cortege of Thomas Paine."[11]

The burial location of Thomas Paine in New Rochelle, New YorkA few years later, the agrarian radical William Cobbett dug up and shipped his bones back to England. The plan was to give Paine a heroic reburial on his native soil, but the bones were still among Cobbett's effects when he died over twenty years later. There is no confirmed story about what happened to them after that, although down the years various people have claimed to own parts of Paine's remains, such as his skull and right hand.

Some believe Paine may have begun to form his early views on natural justice during his childhood, while listening to a mob jeering and attacking those punished in the Thetford stocks.[citation needed] Others have argued that he was influenced by his Quaker father.[citation needed] In The Age of Reason – Paine's treatise in support of deism – he wrote:

The religion that approaches the nearest of all others to true deism, in the moral and benign part thereof, is that professed by the Quakers … though I revere their philanthropy, I cannot help smiling at [their] conceit; … if the taste of a Quaker [had] been consulted at the Creation, what a silent and drab-colored Creation it would have been! Not a flower would have blossomed its gaieties, nor a bird been permitted to sing.

Paine was an early advocate of republicanism and liberalism. He dismissed monarchy, and viewed all government as, at best, a necessary evil. He opposed slavery and was amongst the earliest proponents of universal, free public education, a guaranteed minimum income, and many other ideas considered radical at the time.

In the second part of The Age of Reason, Paine writes about his illness and the fever he suffered while in prison. ". . . I was seized with a fever that in its progress had every symptom of becoming mortal, and from the effects of which I am not recovered. It was then that I remembered with renewed satisfaction, and congratulated myself most sincerely, on having written the former part of 'The Age of Reason.'" The content of the work can be briefly summarized in this quotation:

The opinions I have advanced… are the effect of the most clear and long-established conviction that the Bible and the Testament are impositions upon the world, that the fall of man, the account of Jesus Christ being the Son of God, and of his dying to appease the wrath of God, and of salvation by that strange means, are all fabulous inventions, dishonorable to the wisdom and power of the Almighty; that the only true religion is Deism, by which I then meant, and mean now, the belief of one God, and an imitation of his moral character, or the practice of what are called moral virtues—and that it was upon this only (so far as religion is concerned) that I rested all my hopes of happiness hereafter. So say I now—and so help me God.

With regard to his religious views, in The Age of Reason (begun in France in 1793), Paine stated:

I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.

All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.

He described himself as a "Deist" and commented:

How different is [Christianity] to the pure and simple profession of Deism! The true Deist has but one Deity, and his religion consists in contemplating the power, wisdom, and benignity of the Deity in his works, and in endeavoring to imitate him in everything moral, scientifical, and mechanical.

The first article published in America advocating the emancipation of slaves and the abolition of slavery was written by Paine. Titled "African Slavery in America", it appeared on March 8, 1775 in the Postscript to the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser, more popularly known as The Pennsylvania Magazine, or American Museum.

Paine published his last great pamphlet, Agrarian Justice, in the winter of 1795-96. It further developed ideas proposed in the Rights of Man concerning the way in which the institution of land ownership separated the great majority of persons from their rightful natural inheritance and their means of independent survival. Paine's proposal is now deemed a form of Basic Income Guarantee. The Social Security Administration of the United States recognizes Agrarian Justice as the first American proposal for an old-age pension. In Agrarian Justice Paine writes:

In advocating the case of the persons thus dispossessed, it is a right, and not a charity… [Government must] create a national fund, out of which there shall be paid to every person, when arrived at the age of twenty-one years, the sum of fifteen pounds sterling, as a compensation in part, for the loss of his or her natural inheritance, by the introduction of the system of landed property; And also, the sum of ten pounds per annum, during life, to every person now living, of the age of fifty years, and to all others as they shall arrive at that age.

Legacy

Statue of Thomas Paine in Thetford, Norfolk, Paine's birthplaceThomas Paine's writings had great influence on his contemporaries, especially the American revolutionaries. His books inspired both philosophical and working-class Radicals in the United Kingdom; and he is often claimed as an intellectual ancestor by United States liberals, libertarians, progressives and radicals. Both Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Alva Edison read his works with respect.

Lincoln is reported by William Herndon to have written a defense of Paine's deism in 1835 that was burned by Lincoln's friend Samuel Hill as a gesture meant to save Lincoln's political career.

Edison said of Paine:

I have always regarded Paine as one of the greatest of all Americans. Never have we had a sounder intelligence in this republic… It was my good fortune to encounter Thomas Paine's works in my boyhood… it was, indeed, a revelation to me to read that great thinker's views on political and theological subjects. Paine educated me then about many matters of which I had never before thought. I remember very vividly the flash of enlightenment that shone from Paine's writings and I recall thinking at that time, 'What a pity these works are not today the schoolbooks for all children!' My interest in Paine was not satisfied by my first reading of his works. I went back to them time and again, just as I have done since my boyhood days.[14]

There is a museum in New Rochelle, New York in his honour and a statue of him stands in King Street in Thetford, Norfolk, his place of birth. The statue holds a quill and his book, Rights of Man. The book is upside down. NYU also has a bust of Thomas Paine in their pantheon of heroes. Two additional statues of Paine are displayed in Morristown, New Jersey and Bordentown, New Jersey.

Thomas Paine Links

- Thomas Paine Society

- Thomas Paine National Historic Association

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy