Marine veteran remembers Parris Island senior drill instructor who was awarded the Navy Cross with the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines (the “Walking Dead”) in Vietnam and later killed at Con Thien on 6 July 1967.

(SALEM, OR) – We changed trains in Washington, D.C. The overnight train from Washington came to an abrupt stop at Yemassee at 0530 on January 26st. We didn’t have to wait for instructions. Two Marines with no nonsense attitudes boarded the train and in tones that only Marines can mimic, quickly got all of us off the train.

The overnight train from Washington came to an abrupt stop at Yemassee at 0530 on January 26st. We didn’t have to wait for instructions. Two Marines with no nonsense attitudes boarded the train and in tones that only Marines can mimic, quickly got all of us off the train.

It had snowed in the North and we were wearing winter coats. We had left the North and winter and gone into another world with palm trees and summer warmth. No need for suntan lotion. While waiting for the bus, we sat at rigid attention on bare bed springs in the wooden Receiving Barracks, interrupted by policing (cleaning) the main street of the town. Once on the bus to Parris Island, those of us who smoked tossed our cigarettes out of the windows, after one Marine NCO let it be known you couldn’t “light up” whenever you felt like it. We were becoming quick learners.

Marine Corps boot camp covers a 13 week training cycle. The Marine Corps has the longest basis training of all the services. Recruits west of the Mississippi go to Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego; while those east of the Mississippi go to Parris Island, South Carolina. The standing joke in the Corps was that “Hollywood” Marines have it easier than those going through Parris Island. Don’t believe it.

Not everyone makes it through Marine Corps boot camp. Enlistment is not a free ticket into the Marines. You have to earn it. We had a number of recruits who couldn’t keep up with the training because of sprained ankles or broken bones. Once healed, they were assigned to another platoon to complete training. I don’t know the “drop-out rate” but you can bet, no one made any calls to their mothers asking to go home.

A Marine Corps boot camp platoon only has one senior drill instructor and one or more junior drill instructors. Senior drill instructors or SDIs are easily identified by their black belts. As want-a-bee Marines, the first and last words out of our mouths when addressing any drill instructor was always “Sir”!

Our SDI was a decorated Korean War veteran who had survived the breakout from the Chosin Reservoir to Wonson in 1950, earning a Silver Star in the process. Besides being a expert shot, he had a drinking problem and suffered from PTSD and repeated bouts of malaria.

Physical beatings were common in Platoon 308. Most were administered by a junior drill instructor. On occasion, the SDI would take part. For example, one recruit (now dead) had his front teeth knocked out for reading a letter from his girl friend after lights out.

Grown men beating-up teenagers is not something the Marine Corps puts on recruitment posters and was, in fact, a direct violation of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

Our SDI challenged other drill instructors for no apparent reason. More than once, it looked like an argument would result in a fist fight on the parade grinder with other drill instructors. At the rifle range, anyone with a “Maggie drawer’s” (missing the target) was hung up on their thumbs by their belt suspender straps. Trust me, you don’t want to repeat this at home.

We did more physical training in the barracks at night, including some after lights out. With a very tight training schedule, this meant that we were often denied needed sleep and not in the best condition for the next day’s events.

Pvt Dixie, a pet mouse, was a “gift” from a graduating 3rd Battalion platoon. One night, our “pet mouse” got out of the GI can, probably with some help from one of the recruits. We spend hours on our hands and knees looking for Pvt Dixie. Sometime around 0300, the dead mouse or a reasonable looking substitute was found and promptly presented to the SDI. A “full military burial” took place behind the 3rd Battalion mess hall mess.

At a reunion in Philadelphia, one former recruit told us the story that may have ended the SDI’s tour on the island. This recruit was a big, heavy set kid who had been the target of special interest by the SDI and a junior drill instructor. Tied to one of the polls in the barracks, he was beaten so badly in the kidneys that the ensuing bleeding required medical attention. Although questioned by Navy corpsmen and a doctor, he denied any beatings.

Soon after this episode, he was on fire watch walking the perimeter outside the barracks when the SDI coming in from liberty marked him for special attention. In a drunken rage, the SDI spat tobacco in his face. In self-defense, the recruit took a swing at the SDI. The encounter was observed by others. This recruit wound up in the Brig (jail), tried at a court martial, charges dismissed, and recycled to another platoon on the island.

In the middle of the training cycle, we woke-up at reveille to find that we now had two SDIs or, at least, there were now two Marine drill instructions with black belts. We didn’t know it, but the Marine Corps had decided to transfer our original SDI off the island.

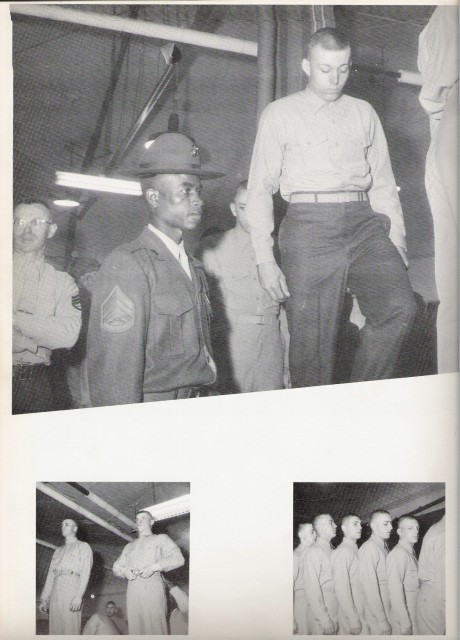

For a few days, SSgt Jettie River, Jr., a black Marine drill instructor and the same rank as our SDI, took the role of an observer. He gave no orders; just watched us go through the day’s training events. To our amazement, our SDI hurled racial insults at him without any reaction.

The clue that “something was up” came when a junior drill instructor who could easily masquerade as the Marquis de Sade read the SDI’s Silver Star citation with tears in his eyes. I doubt if any of us felt the same way. The next thing we knew was he was gone and SSgt Rivers was the new SDI.

SSgt Jettie Rivers, age 29, was an oddity at Parris Island. In 1962, you could count the number of black Marine drill instructors at Parris Island on one hand. A wiry, athletic man from the deep South, he would prove that he didn’t have an ounce of prejudice in his body, even though black men in the South in those days couldn’t eat at a restaurant with whites or even ride in the front of a bus with whites. Racial prejudice was the norm in the South in the 1960s. To this day, it’s hard to believe that Jettie Rivers was not affected by the abuse he experienced growing up in Alabama and Tennessee.

He was an exceptionally fair, discipline man in an environment where others often stepped across the line. He never laid a hand on any recruit, never cursed, never got into your face nor did he tolerate abuse by others.

You can get an idea of what Parris Island was like in gthe 1960’s days by watching “Full Metal Jacket.” Just up the violence in the film by a factor of 10 or so and you should have some idea of how tough things could get.

There was always a price to pay for a “mistake.” All of this changed 180 degrees as soon as SSgt Rivers took over the leadership role of an SDI. No more games or “hazing” and beatings.

As a skinny 19 year old Marine boot, I had difficulty in getting over the obstacle course with my rifle, pack, cartridge belt, canteen, and helmet, ‘782′ gear in Marine speak. Failure would mean a trip to motivation platoon. I didn’t need any motivation, only more arm strength. In his typical quiet way, SSGT Rivers identified the problem and took appropriate corrective action.

I worked on increasing arm strength in the barracks at the end of the training day. Using the pipes hanging from the barrack’s ceiling, I did pull-ups and then dropped to my knees for push-ups until exhausted. All of this was done without abusive language or physical force. Within a week, I was keeping pace with the rest of the platoon. By the end of boot camp, I could do one arm push-ups with either arm.

Platoon 308, S Company, 3rd Battalion, Marine Corps Recruit Depot, Parris Island graduated with 75 Marines in May 1962. We are much older now but none of us can forget Parris Island and Jettie Rivers, Jr.

In 1962, Marines would not be involved in Vietnam for another three years. Some of us got to Nam.

I started looking for “survivors” of Platoon 308 in April 2006. Thanks to the internet and some good people, mostly vets, lending a helping hand I found 55 of the 75 original boot camp platoon members.

A number of Marines made the trip to Nam including Ernie Cannucci, Pete Cassidy, Peter Bellone, Fred Crowley, Bob Bates, Keith Shepherd, Jack Keleher, Brady Ray Bird, Milt Goings, Anthony Pulowski, Ross Lee Brown, Thomas Tucker, Jim McDonald, and Dave Klauder.

The 9th Marines–the first American ground forces in Vietnam–didn’t go ashore at Da Nang until March 1965. By then we were in our third year of active duty. In 1965, Dave Klauder, my boot camp buddy from Pennsylvania, and I were stationed with the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing (MAW) at Iwakuni, Japan. We both signed up for 4 year enlistments with aviation guaranteed.

Dave Klauder went with SATS (Short Air Tactical Systems) in May 1965, the 4th Marines and several hundred Seabees to a no named site 55 miles south of Da Nang. It was promptly named “Chu Lai”, General Krulak’s name in Mandarin Chinese. Dave was a sergeant at the time so no one questioned him filming the landing from the assault craft with an 8mm camera. As Dave tells the story, the Navy was bombarding the beach at the time. Lucky for him, no VC (Vietnamese Communists) were shooting back.

The landing was unopposed and the Seabees and the Marines in SATS built an airfield on a 4,000-foot strip of aluminum matting. Dave spent several months at Chu Lai returning to Iwakuni a good 50 pounds lighter before rotating back to the states.

The build-up of Marine forces in Vietnam picked-up speed in ‘66 and ‘67. Marines were involuntarily extended 120 days in ‘66. So much for a January discharge.

I spent my last four months on active duty assigned to the 4th Marine Aircraft Wing Headquarters, Marine Barracks, Naval Air Station, Glenview, Illinois. Rumor (in Marine speak “scuttlebutt”) had it that the Corps had plans to invade North Vietnam and needed to call up the 4th Marine Division and the 4th Marine Aircraft Wing. In fact, the Marine Corps reserves were never called-up. The call-up would require Congressional approval and President Johnson didn’t have the votes to pull it off. Scrap the invasion of North Vietnam.

One Marine who didn’t come back from Vietnam was Jettie Rivers, Jr. During the Vietnam War, the 1st Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment (1/9 for short) earned the name of “The Walking Dead” for its high casualty rate. The battalion endured the longest sustained combat and suffered the highest killed in action (KIA) rate in Marine Corps history. The battalion was engaged in combat for 47 months and 7 days, from 15 June 1965 to 19 October 1966 and 11 December 1966 to 14 July 1969. With typical battalion strength of 800 Marines and Navy hospital corpsmen, 94% (747) were killed in Action (KIA) over this period. Any Marine assigned to 1/9 during this period was very lucky to be alive. Jettie Rivers, Jr. was not one of the lucky ones.

First Sergeant Jettie Rivers was killed with Captain Richard J. Sasek, Commanding Officer, D/1/9, HM2 John J. Van Vleck, (Corpsman with D/1/9), Cpl Joseph W. Barillo, and LCpl Edward M. Brady, on 06 July 1967 at Con Thien, RVN, by the same enemy incoming fire. He was survived by a wife and two children and is buried in Arlington.

The Marine Corps posthumously promoted FSgt Jettie Rivers to 2nd Lieutenant, not a common action. If the streets of Heaven are guarded by U.S. Marines, the Lord couldn’t find a better platoon leader.

Jettie Rivers’ Navy Cross citation speaks to the courage of the man and his willingness to go to the aid of other Marines, regardless of the consequences.

Second Lieutenant

D CO, 1ST BN, 9TH MARINES, 3RD MARDIV

United States Marine Corps

09 November 1932 – 06 July 1967

Nashville, TN

Panel 23E Line 022

The President of the United States

takes pride in presenting the

NAVY CROSS to

JETTIE RIVERS, JR., First Sergeant

United States Marine Corps

For service as set forth in the following CITATION:

For extraordinary heroism as Company First Sergeant while serving with Company D, First Battalion, Ninth Marines in the Republic of Vietnam on 14 and 15 May 1967. While engaged in search-and-destroy operations against units of the North Vietnamese Army, Company D became engaged with an estimated reinforced enemy company and Second Lieutenant (then First Sergeant) Rivers, a member of the company command group, was wounded. Realizing that the enemy had forced a gap between the command group and one platoon and the two rear platoons, he immediately informed the company commander. At dusk the enemy fire and mortar barrages intensified, and as casualties mounted, the two separate elements set up a hasty perimeter of defense. Second Lieutenant Rivers expertly directed his men’s fire, placed personnel in strategic positions, and personally participated in repelling the enemy assault. Observing a number of enemy soldiers maneuvering toward the perimeter, he mustered a small force of Marines and personally led them to meet the enemy, killing several of the enemy soldiers. When evacuation of the wounded was completed, Second Lieutenant Rivers requested permission to take the point in an attempt to link up the smaller element with the other two platoons. A short distance from the perimeter, the group encountered withering machine-gun fire which instantly killed the platoon sergeant and seriously wounded the platoon leader. Second Lieutenant Rivers immediately took command of the situation, aiding the wounded and personally pinning down the enemy machine gun while the casualties were removed. Now under complete darkness and subject to continuous enemy crossfire and sporadic mortar barrages, Second Lieutenant Rivers assisted in joining the two units. Discovering that all of the platoon leaders had become casualties, he assisted the company commander in setting up an effective perimeter and personally supervised the medical evacuation preparations. Presently a deadly mortar barrage precipitated an all-out enemy assault on the company. Second Lieutenant Rivers was everywhere – encouraging the men, directing fire, assisting the wounded, and distributing ammunition to critical positions. Wounded himself, he continued this pace until late in the afternoon when relief arrived. By his initiative, devotion to duty, and aggressive leadership, he served to inspire all who observed him and was instrumental in saving the lives of many Marines. His great personal valor reflected great credit upon himself, the Marine Corps and the United States Naval Service.

Robert O’Dowd served in the 1st, 3rd and 4th Marine Aircraft Wings during 52 months of active duty in the 1960s. While at MCAS El Toro for two years, O’Dowd worked and slept in a Radium 226 contaminated work space in Hangar 296 in MWSG-37, the most industrialized and contaminated acreage on the base.

Robert is a two time cancer survivor and disabled veteran. Robert graduated from Temple University in 1973 with a bachelor’s of business administration, majoring in accounting, and worked with a number of federal agencies, including the EPA Office of Inspector General and the Defense Logistics Agency.

After retiring from the Department of Defense, he teamed up with Tim King of Salem-News.com to write about the environmental contamination at two Marine Corps bases (MCAS El Toro and MCB Camp Lejeune), the use of El Toro to ship weapons to the Contras and cocaine into the US on CIA proprietary aircraft, and the murder of Marine Colonel James E. Sabow and others who were a threat to blow the whistle on the illegal narcotrafficking activity. O’Dowd and King co-authored BETRAYAL: Toxic Exposure of U.S. Marines, Murder and Government Cover-Up. The book is available as a soft cover copy and eBook from Amazon.com. See: http://www.amazon.com/Betrayal-Exposure-Marines-Government-Cover-Up/dp/1502340003.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy