Who Killed Jack Wheeler?

By Peter Eisler USA Today

NEW CASTLE, Del. — Someone’s been in here, Robert Dill thought as he walked through his neighbor’s house on the morning of Dec. 30.

That much seemed obvious even then — one day before his neighbor Jack Wheeler turned up dead at a landfill 7 miles away.

Dill, 73, had gone to check the Wheeler house after noticing an upstairs window open. He remembered locking all of them when he and his wife had tidied Wheeler’s aged brick duplex a few days earlier.

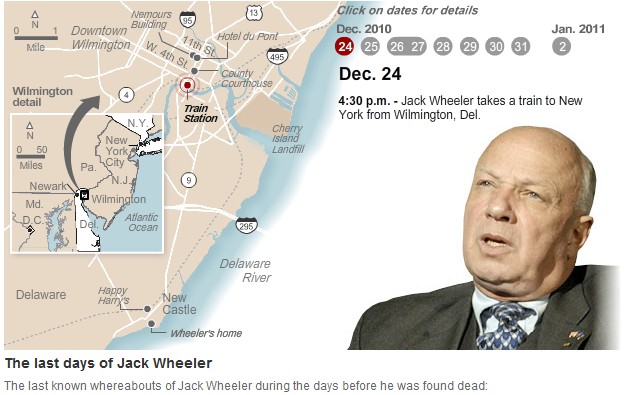

A former Pentagon official and a driving force behind the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Wheeler traveled often — mostly by train between Washington, New York and New Castle. Dill sometimes watched the house when Wheeler was away.

Speaking publicly for the first time about what he saw the day Wheeler vanished, Dill told USA TODAY that he wondered whether he had stumbled onto a crime scene. A side door to the house was open — not much, just a crack. Chairs had been knocked over, and the radios were silent. Dill had left them on a few days before. That’s how Wheeler liked it when he was gone: radios on and tuned to NPR. As he once told Dill, the sound made it seem as though someone was home.

In the kitchen, broken plates sat in the sink. A tall plant had been overturned. And Wheeler’s cadet sword from West Point lay on the floor, unsheathed. Dill remembers a heavy dusting of Comet cleanser on the kitchen’s wood plank floor — and what he believes was the print of a bare foot in the powder.

Had Wheeler, who battled bipolar disorder, simply become unhinged, trashed his house and left? That wasn’t the Jack Wheeler he knew, Dill says. If Wheeler’s home had been robbed, nothing seemed to be missing — not the sculptures nor the paintings Wheeler’s wife, Katherine Klyce, collected. Not the TV or the stereo.

Dill says he decided to first call Wheeler and his wife, rather than police. He left voicemails for both. He never heard back.

Not until the next day, New Year’s Eve, would Dill call 911 to report the strange conditions at the Wheeler house.

Less than 90 minutes after his call, a 911 dispatcher took another report, this time from a worker at the Cherry Island Landfill just north of New Castle. A body had tumbled from a garbage truck, and with it, a mystery.

What happened to Jack Wheeler?

Who killed him?

And why?

New details of a whodunit

For the better part of two days before his body was found, Jack Wheeler had fallen out of contact with his world.

Usually tied to his cellphone and e-mail, he went silent. He somehow got from his home to Wilmington — about 8 miles away — where video cameras at various locations showed him wandering about, disheveled and seemingly confused. In the last of the grainy videos, taken hours after Dill found Wheeler’s house in disarray, he’s seen walking down the street toward one of the city’s rougher neighborhoods, pulling up the hood of a sweatshirt.

Less than 12 hours later, his body was spotted at the landfill. It was in one of the 10 Dumpsters picked up that morning by a trash truck in Newark, Del., a city nearly 15 miles from where Wheeler was last seen. The coroner concluded that Wheeler had been killed. Cause of death: blunt force trauma, likely the result of a beating.

Today, seven weeks after Wheeler’s body was discovered, the killing has become a confounding nightmare for Wheeler’s friends and family, and a whodunit for police.

Neither the intense publicity surrounding the case nor the $25,000 reward offered by Wheeler’s family has yielded a viable suspect. Though police returned to the Wheeler house last week and have removed the part of the kitchen floor where Dill saw the footprint, they concede they have no idea where Wheeler was killed, or why.

“There are a lot of things we still don’t know,” says Lt. Mark Farrall, spokesman for the Newark Police Department.

Police offer few particulars, but in interviews with Wheeler’s neighbors, USA TODAY learned previously undisclosed details about the state of Wheeler’s house on the day he disappeared, and about a man who appeared to be trying to burn down a house across from the Wheelers’ two nights before.

The details might offer new insights into Wheeler’s disappearance and death. Or, like many of the other bits of information from Wheeler’s final days, they may deepen what seems an intractable mystery. A range of Internet conspiracy theories have surfaced, many linking the killing to Wheeler’s stint as a senior Pentagon official with access to secret information during the Bush administration.

As far-fetched as those theories might seem — one has government agents killing Wheeler because he was going to blow the whistle on secret tests of chemical weapons slated for use in Afghanistan — Wheeler’s wife wonders whether someone may have been hired to kill her husband.

“I think perhaps no one has been on the reward because they’ve already been paid,” Klyce told the online magazine Slate. She pointed to where authorities found his body — in a landfill. “The way they disposed of his body, it’s a miracle anybody ever found it. That just sounds like a pro to me.”

Klyce would not talk with USA TODAY, but the lawyer hired to represent the family during the investigation says her feelings are more nuanced than what she told Slate. “Ms. Klyce is distraught and frustrated that she doesn’t know what happened to her husband,” lawyer Colm Connolly says. “At times, she speculates it was a random act; at times, she speculates it was a targeted killing.”

As police work to reconstruct what happened in the days leading up to his death, the questions they face are daunting. Perhaps most important: trying to make sense of a series of disparate and perplexing events.

Does a critical clue lie somewhere in Wheeler’s last days?

Emotional and forgetful

John Parsons Wheeler III — Jack to those who knew him — graduated near the top of the famed West Point Class of ’66 and was a key figure in The Long Gray Line, a seminal book that followed that class through Vietnam. There, the class suffered the highest casualty rate of any at the academy. Fitting, then, that Wheeler later would be a driving force in getting the Vietnam Veterans Memorial built on the National Mall.

He was similarly accomplished in the civilian world — an MBA from Harvard, a law degree from Yale, an appointment as secretary of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. He held notable positions at the Pentagon, including a stint as a top assistant to the secretary of the Air Force from 2005 through 2008.

He also devoted himself to causes outside government: four years as chairman and CEO of Mothers Against Drunk Driving and another four as president of the Deafness Research Foundation.

In recent months, he’d been spending a few days a week in the capital, where MITRE had hired him as a part-time consultant. His job: to facilitate discussions among government, industry and academia on cybersecurity, an issue in which Wheeler had immersed himself for years.

At times, colleagues found him moody and emotional. He sometimes got worked up almost to the point of tears at Pentagon senior staff meetings. More than once, he was barred from an online Class of ’66 forum for posting personal or abusive attacks when he was upset with someone’s position on an issue important to him.

“He could exhibit a high level of frustration and got agitated at colleagues who opposed him, but he was always compassionate,” says former Air Force secretary Michael Wynne, Wheeler’s ex-boss and a West Point classmate. “His determination was just bulldozer-like and always for the little guy.”

Wheeler struggled with depression and bipolar disorder, taking medication to help control the problems. Friends and family suspect he had a touch of Asperger’s syndrome, a form of autism that can affect a person’s ability to handle social contacts properly. Often, he was absent-minded. He occasionally left his car at the Wilmington train station, forgetting it was there and taking a cab home.

Wheeler spent Christmas in New York at a condo he and his wife owned — a ninth-floor unit on 124th Street in the heart of Harlem. The two had been married for more than 13 years, and they each had two children — now grown — from previous marriages. She worked in New York, and the couple split time between the condo and the house in New Castle.

Wheeler had arrived on Christmas Eve and stayed several days. He seemed like his normal self, Connolly says. He posted some messages on the West Point class forum, including a reflective piece on Christmas Day that talked at length about memories from the academy and classmates lost in Vietnam. The next day, Dec. 26, a blizzard hammered the city, and Wheeler posted a photo of the snow from his condo window. On Dec. 27, he made more posts.

One of his last messages was a critique of the government’s preparedness for cyberattacks.

“In cyberspace and on power grid, U.S. is standing around in boxer shorts,” he wrote.

That night, Dec. 27, Wheeler had dinner in the city with friends.

Earlier in the day, he had told his wife that he had to leave the next morning for Washington to take care of a few things; Klyce wanted him to stay longer and felt annoyed, Connolly says. The week from Christmas to New Year’s was one of her favorites, a chance to relax, spend some downtime together, maybe go out for dinner. But Wheeler’s mind was set, and as was often the case, there would be no changing it.

Wheeler left before dawn the next morning, Dec. 28, to catch an early train for Washington.

His family had seen him alive for the last time.

Dec. 28: ‘It was a guy’

Around 11:30 that night, B. Scott Morris, one of Wheeler’s neighbors, was in bed watching TV when he heard a loud thud from outside.

It’s got to be kids messing around in thathouse being built across the street, he thought.

Morris, 44, went to the window and peered out at the house, a stark silhouette perched alone on the edge of a stretch of parkland along the Delaware River. A glow shone from inside, out the unfinished windows.

Morris heard another thud and the glow grew brighter.

Had a homeless man gone inside? Maybe lit a fire in a trash can to keep warm? Morris went downstairs to get a better look from his living room.

That’s when he saw him: a man, thick and average height, wearing a light-colored hooded sweatshirt and dark sweat pants. Morris watched as he tossed what looked like a ball of fire through the opening of a first-floor window. Thud. Then another. Thud. His motion was easy, like a pitcher in softball, and licks of flame clung to his gloved hand after each toss. To Morris, it seemed that some sort of accelerant was sticking to him.

Morris opened the front door and flicked on the light. The man turned and walked calmly into the open parkland next to the house, heading toward the riverbank. Morris hurried to his phone and dialed 911. He never got a look at the man’s face.

Firetrucks were dispatched at 11:36 p.m., and by the time they got there a few minutes later, it looked to Morris like the flames had gone out by themselves. The police came, too, and Morris told them about the man he had seen at the house.

A short time later, the police returned to the house and said they’d found a couple of teenagers in the park with unlit roman candles. Morris was adamant. It wasn’t them. “No, it was a guy,” Morris said. “He walked down towards the river path.”

The teenage boys also told police they had seen a man. Morris, speaking publicly about that night for the first time, recalls that the police seemed unconvinced.

Investigators with the state fire marshal’s office found smoke bombs in the house — the sort of devices commonly used in pest control to flush rodents from their burrows. The damage was limited to some scorched plywood flooring. The boys were cleared almost immediately, and no other suspects have been identified publicly by investigators.

Was it Wheeler?

Wheeler and his wife had been fighting to stop construction of the house, which blocked the sweeping river view from their front porch. Standing on the edge of the open riverfront parkland, it sticks out as a big, new building in a quaint historic district filled with smaller, antique row houses and colonial-style homes, some dating to the early 1700s.

In a series of legal challenges, the Wheelers argued that the project violated regulations aimed at preserving the area’s historic character. They were among dozens of neighbors who signed a petition opposing it.

Wheeler spoke fiercely against it, calling it an affront to the historic character of an area where William Penn first set foot on American soil in 1682. His emotions ran so high that he once lit into Dill for not being outraged enough.

“Would William Penn have wanted that house on this historic piece of land?” he demanded, his voice rising.

Beginning the night of the fire — Dec. 28 — Wheeler’s whereabouts are largely a mystery, punctuated only by a few puzzling sightings and the snippets of footage from the surveillance cameras he happened to pass.

He had spent much of that day, a Tuesday, in Washington, but if anyone knows where he was or what he was doing, they haven’t said so publicly.

Wheeler posted a couple of messages to the Class of ’66 forum that afternoon. The last, sent at 5:10 p.m., seems an unremarkable comment about his gripes with what he saw as corruption in the NCAA’s management of college sports.

At the end of that day, he was scheduled to ride the train to Wilmington, about an hour and a half by Amtrak. Police say he made it back, though they’re not sure he was on the train he had planned to take.

Locals at a bar and bistro up the street argue about whether Wheeler was the man Morris saw tossing the fire balls late that night. A Philadelphia TV station reported after his slaying that investigators had found his iPhone in the fire-bombed house. Police have not confirmed the report and haven’t identified Wheeler as a suspect in the fire. Fire investigators never got a chance to talk to him. Whether Wheeler was home when the firetrucks pulled up remains unclear. If he was, he didn’t come outside.

Could the man tossing the fire bombs have been Wheeler? Morris says he doesn’t think so.

“He was built like Wheeler, but to me, I just don’t think it was him,” Morris says. “I know smart people do stupid things, but it just doesn’t make sense. And the guy didn’t even try to run away. He was really calm. It still puts a chill down my spine.”

Morris and others wonder: If the man wasn’t Wheeler, who was he? And could he be connected to the Wheeler killing?

Dec. 29: Wheeler’s last e-mail?

The next public sighting of Wheeler came at 8:45 the following morning — Wednesday, Dec. 29.

Wheeler was back at the Wilmington train station, about 6 miles from his house. His car was in a garage nearby (after he was killed, police found it in the spot where he left it before his stop home on Christmas Eve, and garage records indicated it had not been moved). Instead of picking up the car, he grabbed a cab that morning. It’s unclear how he got to the train station or whether he came from home.

“Hotel du Pont.”

Roland Spence glanced back at the man who’d hopped into his cab.

Wheeler wore a sport coat and slacks. No suit, no coat. No luggage. Not even a briefcase. Not the usual businessman type, Spence thought.

The ride was short, less than a mile, and Wheeler was chatty and relaxed, Spence recalls. They talked about the hotel, a grand old building with luxury suites that has hosted everyone from Charles Lindbergh to President Kennedy.

“I wouldn’t stay there,” Wheeler told Spence. “Not worth the money.”

Must be meeting someone, Spence thought.

At the hotel, Wheeler hopped out of the cab, handing Spence $12 for a $9 fare.

Less than an hour later, Wheeler sent an e-mail to his daughter Kate — nothing alarming, just benign chatter. The family can tell from the e-mail that it did not come from Wheeler’s iPhone, says Connolly, a former U.S. attorney now with the Morgan Lewis law firm.

“We have asked the authorities to track down the IP address for the computer that was used to send the e-mail,” he says.

For the next eight hours, the man who was always in touch went dark.

Then, around 6 p.m., Wheeler walked into the Happy Harry’s drug store several blocks from his house in New Castle. He headed toward the prescription area in back and approached Murali Gouro at the counter. The pharmacist knew him. He considered Wheeler a regular. Tonight, something seemed odd. Gouro thought Wheeler looked a little upset.

“Can you give me a ride to Wilmington?” Wheeler asked.

Gouro couldn’t but offered to call Wheeler a cab. Wheeler declined and left.

‘I’ve been robbed’

Forty minutes later, Wheeler was back in downtown Wilmington. There, surveillance cameras show him in the parking garage at the New Castle County Courthouse. In the video, Wheeler appears slightly disheveled and maybe a bit confused.

He carries his right shoe in his left hand, his gait slightly lopsided, perhaps because he is wearing one shoe. He had changed at some point in the day — in the video he wears a black suit with a white shirt, a different outfit from what he had on when he took the cab to the Hotel du Pont that morning. In the video at the parking garage, Wheeler walks past the attendant’s window, then backtracks to say a few words to the person behind the glass. He jabs his finger for emphasis before turning again and walking out.

The attendant called security, suspecting Wheeler may have been homeless.

Cathleen Boyer, one of the courthouse guards, got the call just before 7 p.m. She and a couple of state workers ran into Wheeler as he left the garage’s lower level. Boyer looked him over. She says she noticed some dirt on his right pants leg but he didn’t smell of liquor.

His eyes … they were red. Like he’s been crying or something, Boyer thought.

“I’ve been robbed,” Wheeler told them. His briefcase, he said, had been stolen. Boyer and the workers asked whether he was OK. They offered him money. Wheeler wouldn’t take it. “I have plenty of money,” he said.

He told them he was staying at a nearby hotel, Boyer recalls, and then mentioned something about his brother and mother before walking off.

From there, Wheeler’s movements became even more mystifying. He wasn’t registered at the Hotel du Pont, and police, despite canvassing nearby hotels and shelters, haven’t figured out where he spent the night.

Dec. 30: The last sightings

The next day — Dec. 30, the day his neighbor Gill discovered Wheeler’s home in disarray — Wheeler was spotted in downtown Wilmington again.

He was at the Nemours Building, a historical, 14-story landmark with shops and a cafe in the lobby, apartments and business suites on the upper floors.

In the midafternoon, police say, several people saw him wandering around the lobby, looking disoriented. They asked whether he needed help. Wheeler declined. He went to the 10th-floor offices of the Connolly Bove Lodge & Hutz law firm and asked to speak to a managing partner. The firm has no connection to the newly hired Wheeler family lawyer Connolly, and it’s unclear why Wheeler stopped there.

Wheeler didn’t stay long. He left before speaking to the partner, stopping to ask for train fare on the way out. The request seems especially strange given that the night before, after saying he had been robbed, Wheeler told the courthouse guard that he still had “plenty of money.”

At around 8:30 p.m., surveillance cameras show him leaving the building. By then, he was wearing a dark, hooded sweatshirt, clothing that friends and family say they had never seen on him. As he walked out, he pulled the hood over his head.

A few minutes later, a camera around the corner at the Hotel du Pont valet station shows him walking down the street. He disappeared from view at 8:42 p.m., Thursday, Dec. 30, headed toward the city’s rough East side.

To date, few tips

The trash truck that picked up Wheeler’s body had emptied 10 Dumpsters before it dropped its load at the landfill Dec. 31. All of the Dumpsters were in Newark, about a half-hour away by car from the part of Wilmington where Wheeler was last seen.

Some of the Dumpsters where his body could have been left are in plain view — outside a McDonald’s and a bank. Others are more remote — behind a Goodwill store, in an alley behind the library. Although video cameras are trained on some of them, none appears to have captured clues to solve the case.

For the family, the weeks since Wheeler’s death have been trying. “They’re frustrated by the apparent lack of progress in the investigation and the unwillingness of authorities to share information with them,” lawyer Connolly says. When the medical examiner announced the cause of death, the family learned the findings through the news media, Connolly says.

At the end of January, a month after Wheeler’s death, the family offered the $25,000 reward. Police set up a tip line but say they’ve been disappointed by what has come in.

Residents of New Castle talk about whether Wheeler simply suffered a breakdown, losing his grip on reality and wandering into the wrong neighborhood. Maybe he antagonized the wrong person; maybe a robbery became a homicide.

Others, including some neighbors and friends, say that theory leaves too many unanswered questions. Did dumping a body 15 miles from where Wheeler was last seen indicate that he was killed by a professional, as Wheeler’s wife has speculated? And what about the man who fire-bombed the house across from Wheeler’s?

Friends who watched the surveillance video taken in Wheeler’s final hours found it disturbing to see a man known for his sharp intellect in such a bewildered state.

Jeff Rogers was close to Wheeler for six decades, since grade school. They double-dated together as teens, attended West Point together, and when Rogers married, Wheeler was his best man. When he saw the tape, some of the physical mannerisms rang true — the arm outstretched during a moment of thought. But the man in the video wasn’t the Jack Wheeler he knew.

“The physical disorientation, the lack of control, walking around with one shoe, none of that was Jack,” Rogers says. “It was completely unlike him. I don’t know what happened, but something happened to him.”

In April, Rogers will be among scores of family, friends and admirers who are likely to attend a memorial service for Wheeler in the chapel at Arlington National Cemetery. They’ll remember a life of achievement, a life well lived. By then, they hope these questions might have answers: What happened to Jack Wheeler? Who killed him? And why?

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy