by Denise Nichols

With the Appropriations Committee Full vote on Tuesday morning this week. The Full Defense Bill that the DOD CDMRP Funding is a small part gets one step closer to coming to the House of Representative Floor for full Vote. There is sure to be debates and amendments from the floor before the work on House Side is done and it is sent to Senate Side. It is a long process to get the Appropriations and Authorizations bills through the full legislative process. We are in the middle now in the House. Then the action moves to the Senate step by step process. Then the two houses have to come together in a conference committee to work out differences before it is finally approved formally and eventually gets to the President’s desk.

The House side has already held many meetings at Subcommittee level to receive input and come up with the areas of the bill that the subcommittees cover and then it comes all together for full committee. Each step there can be lively discussion and amendments considered and voted upon. Now we are at the point of the Defense Appropriations Bill waiting its turn on the House Calender. Amendments from the floor are expected. The Rules Committee sets the rules that handles the procedural process.

So as we wait let us discuss the specifics in the DOD Congressional Directed Medical Research Program appropriations funding.

Number 22 on the list to be funded by the DOD CDMRP Program is Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) last year 6,400 to this year House DOD APPROPRIATIONS DOD Bill is 5,100

Now for those that don’t know what this disease is I found this fact sheet to share: First Read it then we have several questions to address.

- What is Tuberous Sclerosis?

- What causes Tuberous Sclerosis?

- Is TSC inherited?

- What are the signs and symptoms of TSC?

- How is TSC diagnosed?

- How is TSC treated?

- What is the prognosis?

- What research is being done?

- Where can I get more information?

What is Tuberous Sclerosis?

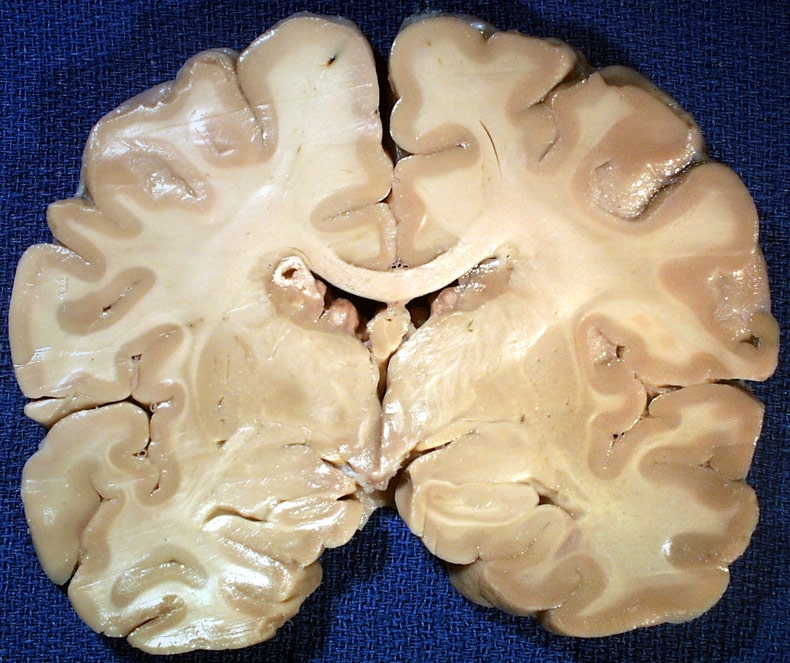

Tuberous sclerosis–also called tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC)1–is a rare, multi-system genetic disease that causes benign tumors to grow in the brain and on other vital organs such as the kidneys, heart, eyes, lungs, and skin. It commonly affects the central nervous system and results in a combination of symptoms including seizures, developmental delay, behavioral problems, skin abnormalities, and kidney disease.

The disorder affects as many as 25,000 to 40,000 individuals in the United States and about 1 to 2 million individuals worldwide, with an estimated prevalence of one in 6,000 newborns. TSC occurs in all races and ethnic groups, and in both genders.

The name tuberous sclerosis comes from the characteristic tuber or potato-like nodules in the brain, which calcify with age and become hard or sclerotic. The disorder–once known as epiloia or Bourneville’s disease–was first identified by a French physician more than 100 years ago.

Many TSC patients show evidence of the disorder in the first year of life. However, clinical features can be subtle initially, and many signs and symptoms take years to develop. As a result, TSC can be unrecognized or misdiagnosed for years.

What causes Tuberous Sclerosis?

TSC is caused by defects, or mutations, on two genes-TSC1 and TSC2. Only one of the genes needs to be affected for TSC to be present. The TSC1 gene, discovered in 1997, is on chromosome 9 and produces a protein called hamartin. The TSC2 gene, discovered in 1993, is on chromosome 16 and produces the protein tuberin. Scientists believe these proteins act in a complex as growth suppressors by inhibiting the activation of a master, evolutionarily conserved kinase called mTOR. Loss of regulation of mTOR occurs in cells lacking either hamartin or tuberin, and this leads to abnormal differentiation and development, and to the generation of enlarged cells, as are seen in TSC brain lesions.

Is TSC inherited?

Although some individuals inherit the disorder from a parent with TSC, most cases occur as sporadic cases due to new, spontaneous mutations in TSC1 or TSC2. In this situation, neither parent has the disorder or the faulty gene(s). Instead, a faulty gene first occurs in the affected individual.

In familial cases, TSC is an autosomal dominant disorder, which means that the disorder can be transmitted directly from parent to child. In those cases, only one parent needs to have the faulty gene in order to pass it on to a child. If a parent has TSC, each offspring has a 50 percent chance of developing the disorder. Children who inherit TSC may not have the same symptoms as their parent and they may have either a milder or a more severe form of the disorder.

Rarely, individuals acquire TSC through a process called gonadal mosaicism. These patients have parents with no apparent defects in the two genes that cause the disorder. Yet these parents can have a child with TSC because a portion of one of the parent’s reproductive cells (sperm or eggs) can contain the genetic mutation without the other cells of the body being involved. In cases of gonadal mosaicism, genetic testing of a blood sample might not reveal the potential for passing the disease to offspring.

What are the signs and symptoms of TSC?

TSC can affect many different systems of the body, causing a variety of signs and symptoms. Signs of the disorder vary depending on which system and which organs are involved. The natural course of TSC varies from individual to individual, with symptoms ranging from very mild to quite severe. In addition to the benign tumors that frequently occur in TSC, other common symptoms include seizures, mental retardation, behavior problems, and skin abnormalities. Tumors can grow in nearly any organ, but they most commonly occur in the brain, kidneys, heart, lungs, and skin. Malignant tumors are rare in TSC. Those that do occur primarily affect the kidneys.

Kidney problems such as cysts and angiomyolipomas occur in an estimated 70 to 80 percent of individuals with TSC, usually occurring between ages 15 and 30. Cysts are usually small, appear in limited numbers, and cause no serious problems. Approximately 2 percent of individuals with TSC develop large numbers of cysts in a pattern similar to polycystic kidney disease2 during childhood. In these cases, kidney function is compromised and kidney failure occurs. In rare instances, the cysts may bleed, leading to blood loss and anemia.

Angiomyolipomas-benign growths consisting of fatty tissue and muscle cells-are the most common kidney lesions in TSC. These growths are seen in the majority of TSC patients, but are also found in about one of every 300 people without TSC. Angiomyolipomas caused by TSC are usually found in both kidneys and in most cases they produce no symptoms. However, they can sometimes grow so large that they cause pain or kidney failure. Bleeding from angiomyolipomas may also occur, causing both pain and weakness. If severe bleeding does not stop naturally, there may severe blood loss, resulting in profound anemia and a life-threatening drop in blood pressure, warranting urgent medical attention.

Other rare kidney problems include renal cell carcinoma, developing from an angiomyolipoma, and oncocytomas, benign tumors unique to individuals with TSC.

Three types of brain tumors are associated with TSC: cortical tubers, for which the disease is named, generally form on the surface of the brain, but may also appear in the deep areas of the brain; subependymal nodules, which form in the walls of the ventricles-the fluid-filled cavities of the brain; and giant-cell tumors (astrocytomas), a type of tumor that can grow and block the flow of fluids within the brain, causing a buildup of fluid and pressure and leading to headaches and blurred vision.

Tumors called cardiac rhabdomyomas are often found in the hearts of infants and young children with TSC. If the tumors are large or there are multiple tumors, they can block circulation and cause death. However, if they do not cause problems at birth-when in most cases they are at their largest size-they usually become smaller with time and do not affect the individual in later life.

Benign tumors called phakomas are sometimes found in the eyes of individuals with TSC, appearing as white patches on the retina. Generally they do not cause vision loss or other vision problems, but they can be used to help diagnose the disease.

Additional tumors and cysts may be found in other areas of the body, including the liver, lung, and pancreas. Bone cysts, rectal polyps, gum fibromas, and dental pits may also occur.

A wide variety of skin abnormalities may occur in individuals with TSC. Most cause no problems but are helpful in diagnosis. Some cases may cause disfigurement, necessitating treatment. The most common skin abnormalities include:

- Hypomelanic macules (“ash leaf spots”), which are white or lighter patches of skin that may appear anywhere on the body and are caused by a lack of skin pigment or melanin-the substance that gives skin its color.

- Reddish spots or bumps called facial angiofibromas (also called adenoma sebaceum), which appear on the face (sometimes resembling acne) and consist of blood vessels and fibrous tissue.

- Raised, discolored areas on the forehead called forehead plaques, which are common and unique to TSC and may help doctors diagnose the disorder.

- Areas of thick leathery, pebbly skin called shagreen patches, usually found on the lower back or nape of the neck.

- Small fleshy tumors called ungual or subungual fibromas that grow around and under the toenails or fingernails and may need to be surgically removed if they enlarge or cause bleeding. These usually appear later in life, ages 20 – 50.

- Other skin features that are not unique to individuals with TSC, including molluscum fibrosum or skin tags, which typically occur across the back of the neck and shoulders, café au lait spots or flat brown marks, and poliosis, a tuft or patch of white hair that may appear on the scalp or eyelids.

TSC can cause seizures and varying degrees of mental disability. Seizures of all types may occur, including infantile spasms; tonic-clonic seizures (also known as grand mal seizures); or tonic, akinetic, atypical absence, myoclonic, complex partial, or generalized seizures.

Approximately one-half to two-thirds of individuals with TSC have mental disabilities ranging from mild learning disabilities to severe mental retardation. Behavior problems, including aggression, sudden rage, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, acting out, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and repetitive, destructive, or self-harming behavior, often occur in children with TSC, and can be difficult to manage. Some individuals with TSC may also have a developmental disorder called autism.

How is TSC diagnosed?

In most cases the first clue to recognizing TSC is the presence of seizures or delayed development. In other cases, the first sign may be white patches on the skin (hypomelanotic macules).

Diagnosis of the disorder is based on a careful clinical exam in combination with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, which may show tubers in the brain, and an ultrasound of the heart, liver, and kidneys, which may show tumors in those organs. Doctors should carefully examine the skin for the wide variety of skin features, the fingernails and toenails for ungual fibromas, the teeth and gums for dental pits and/or gum fibromas, and the eyes for dilated pupils. A Wood’s lamp or ultraviolet light may be used to locate the hypomelantic macules which are sometimes hard to see on infants and individuals with pale or fair skin. Because of the wide variety of signs of TSC, it is best if a doctor experienced in the diagnosis of TSC evaluates a potential patient.

In infants TSC may be suspected if the child has cardiac rhabdomyomas or seizures (infantile spasms) at birth. With a careful examination of the skin and brain, it may be possible to diagnose TSC in a very young infant. However, many children are not diagnosed until later in life when their seizures begin and other symptoms such as facial angiofibromas appear.

How is TSC treated?

In October 2010 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of everolimus to treat benign tumors called subependymal giant cell astrocytomas in individuals with TSC who require treatment but are not candidates for surgery. There is no cure for TSC, although treatment is available for a number of the symptoms. Antiepileptic drugs may be used to control seizures, and medications may be prescribed for behavior problems. Intervention programs including special schooling and occupational therapy may benefit individuals with special needs and developmental issues. Surgery including dermabrasion and laser treatment may be useful for treatment of skin lesions. Because TSC is a lifelong condition, individuals need to be regularly monitored by a doctor to make sure they are receiving the best possible treatments. Due to the many varied symptoms of TSC, care by a clinician experienced with the disorder is recommended.

Recently much enthusiasm has arisen in regard to the use of rapamycin for treatment of TSC. Rapamycin is a drug that specifically blocks the activity of mTOR. In cell culture experiments and animal models of TSC, rapamycin appears to be very effective. Initial clinical experience with rapamycin and related drugs is also positive, but much additional study is required before these drugs become standard therapy.

What is the prognosis?

The prognosis for individuals with TSC depends on the severity of symptoms, which range from mild skin abnormalities to varying degrees of learning disabilities and epilepsy to severe mental retardation, uncontrollable seizures, and kidney failure. Those individuals with mild symptoms generally do well and live long productive lives, while individuals with the more severe form may have serious disabilities.

In rare cases, seizures, infections, or tumors in vital organs may cause complications in some organs such as the kidneys and brain that can lead to severe difficulties and even death. However, with appropriate medical care, most individuals with the disorder can look forward to normal life expectancy.

What research is being done?

Within the Federal Government, the leading supporter of research on TSC is the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). The NINDS, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), is responsible for supporting and conducting research on the brain and the central nervous system. NINDS conducts research in its laboratories at NIH and also supports studies through grants to major medical institutions across the country. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Cancer Institute, also components of the NIH, support and conduct research on TSC.

Scientists who study TSC seek to increase our understanding of the disorder by learning more about the TSC1 and TSC2 genes that can cause the disorder and the function of the proteins-tuberin and hamartin-produced by these genes. Scientists hope knowledge gained from their current research will improve the genetic test for TSC and lead to new avenues of treatment, methods of prevention, and, ultimately, a cure for this disorder.

Research studies run the gamut from very basic scientific investigation to clinical translational research. For example, some investigators are trying to identify all the protein components that are in the same ‘signaling pathway’ in which the TSC1 and TSC2 protein products and the mTOR protein are involved. Other studies are focused on understanding in detail how the disease develops, both in animal models and in patients, to better define new ways of controlling or preventing the development of the disease. Finally, clinical trials of rapamycin are underway (with NINDS and NCI support) to rigorously test the potential benefit of this compound for some of the tumors that are problematic in TSC patients.

- Tuberous sclerosis is often referred to as tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) in medical literature to help distinguish it from Tourette’s syndrome, an unrelated neurological disorder.

- Polycystic kidney disease is a genetic disorder characterized by the growth of numerous fluid-filled cysts in the kidneys.

- Where can I get more information?

- For more information on neurological disorders or research programs funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, contact the Institute’s Brain Resources and Information Network (BRAIN) at:

BRAIN

P.O. Box 5801

Bethesda, MD 20824

(800) 352-9424

www.ninds.nih.gov

Information also is available from the following organizations:

Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance

- 801 Roeder Road

- Suite 750

- Silver Spring, MD 20910-4467

- [email protected]

- www.tsalliance.org

- Tel: 301-562-9890 800-225-6872

- Fax: 301-562-9870

Epilepsy Foundation

- 8301 Professional Place

- Landover, MD 20785-7223

- [email protected]

- www.epilepsyfoundation.org

- Tel: 301-459-3700 800-EFA-1000 (332-1000)

- Fax: 301-577-2684

National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD)

- P.O. Box 1968

- (55 Kenosia Avenue)

- Danbury, CT 06813-1968

- [email protected]

- www.rarediseases.org

- Tel: 203-744-0100 Voice Mail 800-999-NORD (6673)

- Fax: 203-798-2291

“Tuberous Sclerosis Fact Sheet,” NINDS.

NIH Publication No. 07-1846

Back to Tuberous Sclerosis Information Page

Individual Institutes with a record of funding TSC grants:

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- National Institute of Mental Health

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

- National Cancer Institute

- National Institute of General Medical Sciences

- Office of Rare Diseases

- Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program

- LAM Foundation Epilepsy Foundation

- Child Neurology Foundation

- Resources in Epilepsy Research

Discussion Questions:

The question that should be the highest priority: Is this area of medical concern getting funded through other federal agencies?

Is That Funding sufficient?

Is there outside Non Profit Civilian Organizations fund raising and providing Research Funding? How much did the civilian raised funds for medical research in this are in each of the last 5 years?

The second question is how many in the military population have been diagnosed with this problem?

The third question is how many veterans have been diagnosed with this problem?

Is there any possibly of a potential connection to exposures that the military could have been exposed to during their service?

How many are affected/diagnosed with this illness that are military/veterans?

What priority level should this be given in regards to DOD or military veterans?

When budgets are being cut and some needs are not met in other agencies in relationship to our military/DOD priority levels and decisions must be made. What will they be? And the military members and Veterans should definitely participate and provide comments.

SO the comment forum is now open: I am sure lively comments will follow.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy