By Sir Vojislav Milosevic, Director, Center for Counter-terrorism & World Peace

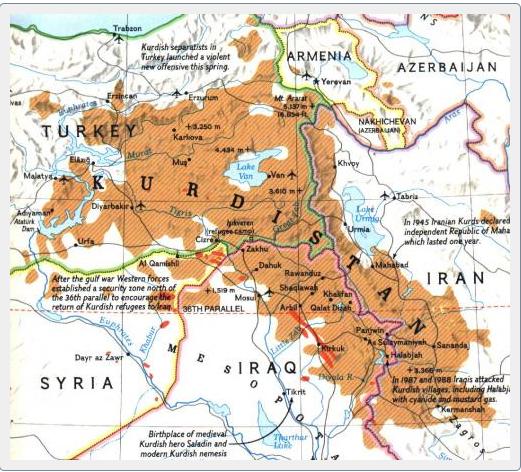

The Kingdom of Corduene, which emerged from declining Selucid Empire, qas located to the south and south-east of Lake Van, between Persia and Mesopotamia and ruled northern Mesopotamia and south-eastern Anatolia from 189 BC to AD 384.

At its zenith, the Roman Empire ruled large Kurdish inhabited areas, particulary the western and northern areas in the Middle East. The Kingdom Corduene became a vassal state of the Roman Republic in 66 BC and remained allied with the Romans until AD 384. The Kingdom of Corduene was situated to the east of Tigranocerta, that is, to the east and south of present-day Diyarbakir in south-east Turkey.

One of the earliest records of the phrase land of the Kurds is found in a Syriac Christian document of late antiquity, describing the stories of Christian saints of the Middle East, such as the Abdisho. When the Sassanid Marzbah asked Mar Abdisho about his place of origin, he replied that according to his parents, they were originally from Hazza, a village in Assyria.

However they were later driven out of Hazza by pagans, and settled in Tamanon, which according to Abdisho was in the land of the Kurds. Tamanon lies just north of the modern Iraq-Turkey border, while Hazza is 12 km southwest of modern Irbil In another passage in the same document, the region of the Khabur River is also identified as land of the Kurds.

Ancient Kurdistan as Kard-uchi, during Alexander the Great’s Empire, 4th century BC

In the 16th century, after prolonged wars, Kurdish-inhabited areas were split between the Safavid and Ottoman empires. A major division of Kurdistan occurred in the aftermath of the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, and was formalized in the 1639 Treaty of Zuhab.

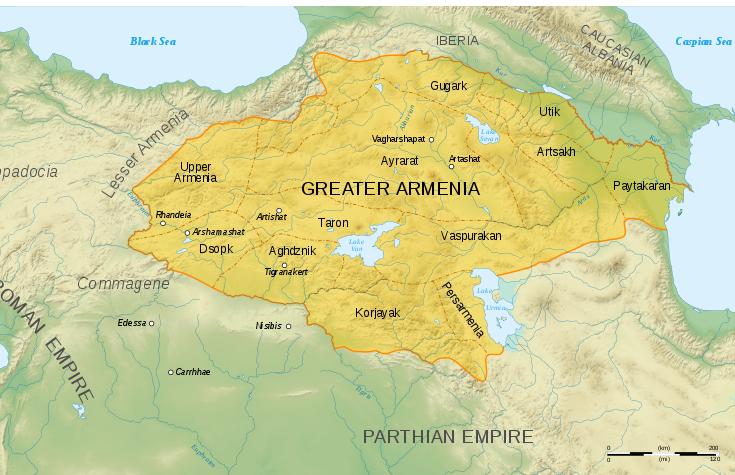

Prior to World War I, most Kurds lived within the boundaries of the Ottoman Empire in the province of Kurdistan]. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Allies contrived to create several countries within its former boundaries – according to the never-ratified Treaty of Sèvres, Kurdistan, along with Armenia, were to be among them.

However, the reconquest of these areas by the forces of Kemal Atatürk (and other pressing issues) caused the Allies to accept the renegotiated Treaty of Lausanne and the borders of the modern Republic of Turkey – leaving the Kurds without a self-ruled region. Other Kurdish areas were assigned to the new British and French mandated states of Iraq and Syria.

An article in the New York Times reported on the trial in Turkey of captured Kurdish guerrilla leader Abdullah Ocalan. The Times provided background on the war between Kurdish separatist guerrillas and Turkish security forces:

The war that Ocalan has waged has cost more than 30,000 lives and made him the object of intense hatred. It has also made him a heroic figure to many Kurds who live in Turkey’s southeast.

Contrast this description with the way the New York Times presents the background of another, very similar, separatist war (3/27/99):

“The Serbian campaign against the ethnic Albanians has seen more than 2,000 killed in the last year, with hundreds of thousands of Kosovars driven from their homes, according to the United Nations.”

The two news articles quoted above appear to assign responsibility for casualties in each war to one or the other side in the conflict: In the case of Turkey, blame for the 30,000, mostly Kurdish, dead goes to the leader of the Kurdish rebels.

In the case of Yugoslavia, blame for the 2,000, mostly ethnic Albanian, dead is put squarely on the shoulders of the Serbian authorities putting down the rebellion.

This disparity is typical in Times coverage of the two conflicts. In an editorial on the Ocalan trial (6/24/99), the Times explained the Kurdish war:

“In response to Mr. Ocalan’s violence, the country’s armed forces have devastated Kurdish-inhabited areas of southeastern Turkey, razing villages, and driving tens of thousands of refugees to Ankara and Istanbul.”

On the other hand, in a March 24/99 editorial about NATO’s bombing (“The Rationale for Air Strikes”), the Times’ editoral writers describe the Kosovo conflict this way:

“Serbian forces are shelling and burning villages, forcing tens of thousands to flee. They have also been killing ethnic Albanian civilians.”

In these editorials, the two very similar conflicts are described in very similar terms. But the editorial about Turkey makes it clear that the security forces are acting “in response to Mr. Ocalan’s violence”; whereas the editorial about Kosovo does not mention the existence of the Kosovar guerrillas at all.

In fact, a reader who knows nothing about the Kosovo conflict would have literally no inkling, from reading this editorial laying out “The Rationale for Air Strikes,” that an insurgency has ever taken place there.

Serbian historical pretext

Kosovo was an integral part of Serbia when the area was conquered by the Turks in the fifteenth century. In Serbian history books it is often called Old Serbia. Albanians began arriving in the seventeenth century during the Turkish occupation. It has been recognized as an integral part of Serbia by the international community since 1912.

When the Axis powers invaded and dismembered Yugoslaviain 1941, they attached Kosovo and Albanian-speaking regions of Montenegro,Macedonia, and Greece to Albaniato form a greater Albania under the rule of a fascist dictator. The Kosovo Albanians formed military units to fight for the Nazis, killed more than 10,000 Kosovo Serbs, and drove more than 100,000 out of the province into the rest of Serbia. They brought immigrants in from Albania to fortify the Albanian presence in the province.

When the Croatian Communist dictator Tito came to power in Yugoslaviain 1945, he forbade the Serbian refugees to return to their homes in Kosovo. He then signed a deal with the new Communist dictator of Albania to bring in another 100,000 Albanian settlers. The Albanian majority in Kosovo appears to date from the years around World War II.

An upsurge of Albanian Kosovo violence in 1969-1974 caused another 200,000 Serbs and Montenegrins to leave Kosovo and gave Tito an excuse to separate Kosovo from Serbia. He made it an autonomous province under the total control of the now Albanian majority.

The KLA (Kosovo Liberation Army) was formed shortly thereafter from a Maoist organization dedicating itself to free Kosovo. As recently as a years ago, the United States government condemned the KLA as a terrorist group, linked closely to Iran, the Islamic fundamentalist Osama bin-Laden, and the heroin traffic in Europe, and put them on the list of the world’s serious terrorist organizations. Europeans have likened it to a Mafia because of its lawless involvement in organized crime, including prostitution.

The stated goal of the KLA is to create a greater Albania by attaching Yugoslav Kosovo and Albanian-speaking regions of Montenegro, Macedonia, and Greece to Albania. Using Albania as a base and conduit for weapons, the KLA began carrying on a terror campaign against the Yugoslav government in Kosovo, assassinating and kidnapping not only Serbs but also Albanians and other ethnic groups who opposed their desires for independence.

Kosovo continues to be home not only to Albanian-speaking Muslims, but also to nearly half a million other people. The goal of the KLA is to create an ethnically pure Kosovo by driving out or culturally assimilating the rest of the population.

Their claims of 1.8 million Albanians in Kosovo are demographically impossible, even with immigration, for there were only 645,000 Albanians in the last full federal census carried out in 1961. There have also been many emigrants from Kosovo to other parts of Yugoslavia and Europe.

Their claims of 1.8 million Albanians in Kosovo are demographically impossible, even with immigration, for there were only 645,000 Albanians in the last full federal census carried out in 1961. There have also been many emigrants from Kosovo to other parts of Yugoslavia and Europe.

With the collapse of the Communist regime in neighboring Albania in the 1990s and the nearly anarchic conditions in that country, more Albanians crossed the porous borders with Yugoslavia into Kosovo.

Within Kosovo, Yugoslav forces were attempting to deal militarily with KLA terrorism. Using as an excuse an alleged massacre of Albanian Kosovars at Racak by Yugoslav security forces in mid-January, 1999, Mrs. Albright and Mr. Clinton demanded to “mediate” at Rambouillet. Themassacre was quickly identified as a KLA set up.

This did not deter Mr. Clinton and Mrs. Albright from pursuing their designs. It is now known that Mr. Clinton had made a decision months earlier to seek to destroy Milosevich. Racak was the pretext.

Why the discrepancy?

The two conflicts are notable for the remarkable parallels between them. In each case, a local ethnic minority has seen its cultural, civil and human rights abused by the central government. In each case, members of the minority responded by organizing an armed guerrilla force in their local territory, aimed at secession and independence. In each case, the guerrillas used terrorism, e.g., sniping at police officers and civilians – to provoke a response from security forces.

And in each case, the security forces responded with overwhelming force, clearing out villages suspected of providing support to the terrorists, all the while claiming they were merely preventing terrorists from threatening the territorial integrity of their country.

In both countries, the human costs of both campaigns were not equal. When the New York Times published its description of the Kosovo campaign, in addition to the 2,000 dead, an estimated 200 villages „had been partly or completely destroyed“, with approximately 450,000 people displaced in one year of heavy fighting, and much more by NATO bombing campaign.

In Turkey, according to Human Rights Watch, 35,000 people have been killed, while more than 3,000 villages have been destroyed, and an estimated 2 million Kurdish people have been displaced in 15 years of fighting.

Doc: NATO’s illegal WAR againgst SERBIA. KOSOVO LIES part2/2

But the two conflicts differ in one crucial respect: The U.S. militarily opposed Yugoslavia’s actions in Kosovo. Turkey, on the other hand, is a close U.S. ally. As a State Department official told reporters in 1992, when Turkey’s human rights abuses were reaching a peak:

“There is no question of halting U.S. military assistance to Turkey. The U.S. sees nothing objectionable in a friendly or allied country using American weapons to secure internal order or to repel an attack against its territorial unity.”

Clearly the U.S. has a double standard when it comes to civil wars – but that doesn’t mean that the New York Times ought to.

Novak Djokovic about Kosovo

Director of Center for Counter Terrorism and World Peace (Centra za Anti-Terorizam i Svetski Mir). Milosevic graduated at the Faculty for Political Sciences in Belgrade in 1980 with postgraduate studies in Islamic fundamentalism. He has worked with UNESCO and UNCTAD, a journalist, counselor at the Protocol of the Federal Parliament, speaker, politician, and book author.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy