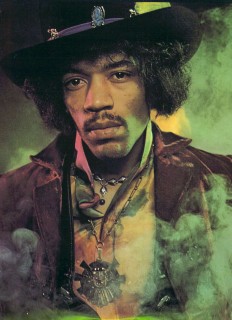

“I can explain everything better though music. You hypnotize people to where they go right back to their natural state, and when you get people at their weakest point, you can preach into their subconscious what we want to say.”—Jimi Hendrix[1]

…by Jonas E. Alexis

In Magick: In Theory and Practice, Aleister Crowley wrote,

“There are three methods for invoking any deity…The Third Method is the dramatic, perhaps the most attractive of all; certainly it is to the artists temperament, for it appeals to his imagination through his aesthetic sense…It is very difficult for the ordinary man to lose himself completely in the subject of a play…but for those who can do so this is unquestionably the best.”[2]

This is certainly not a scientific principle, but it may have some explanatory power and scope that will help us unravel and understand the philosophy that posts beneath much of the entertainment industry.

According to Crowley, directors, screenwriters, but most specifically actors and actresses can be easily possessed by losing themselves completely in the subject of a play.

In other words, actors and actresses could directly or indirectly be possessed if they simply let themselves be inhabited by the characters they are trying to portray.

One way to test this hypothesis is to see how this has played out in ancient history—most specifically in ancient Greece. Then we can test it in our modern times. A third way is to let the actors and actresses speak for themselves.

It must be emphasize that trance, spirit channeling, shamanism, and possession have always played a key aspect in music and art from time immemorial, and African tribal music,[3] which has produced many offshoots such as rap and rock and roll,[4] is no exception.

The word music comes from the Greek word mousike,[5] which entails a spiritual dimension and power.[6] The muses, in ancient Greek mythology, were the nine daughters of Zeus who were the goddesses of inspiration.[7] Central to this ancient phenomenon was that the actors and dramatists would set the stage in such a way as to consciously or unconsciously invite the spirit of the muse—what we would now call spirit entities—to help them with their performances.[8]

This phenomenon is quite ancient and was widespread not only in ancient Greece but also in Rome, Egypt, etc.

In the classic work Music and the Muses: The Culture of ‘Mousike’ in the Classical Athenian City, we read:

“Apart from their extra-discursive and historical identity, the actors and the choreutai of Attic comedy are involved in the action played on the stage as well as in the ritual performed by Dionysus in his sanctuary which is also the theatre.”[9] Classicist Martin Persson Nilsson tells us that Dionysus was also “the god of the theatre.”[10]

The Roman historian Livy wrote what happened during certain rites in this cult (though some have claimed that he exaggerated):

“There were initiatory rites which at first were imparted to a few, then began to be generally known among men and women. To the religious element in them were added the delights of wine and feasts, that the minds of a larger number might be attracted.

“When wine had inflamed their minds, and night and the mingling of males with females, youth with age, had destroyed every sentiment of modesty, all varieties of corruption first began to be practiced. Since each one had at hand the pleasure answering to that to which his nature was more inclined.

“There was not one form of vice alone, the promiscuous matings of free men and women, but perjured witnesses, forged seals and wills and evidence, all issued from this same workshop: likewise poisonings and murders of kindred, so that at times not even the bodies were found for burial.

“Much was ventured by craft, more by violence. This violence was concealed because amid the howlings and the crash of drums and cymbals no cry of the sufferers could be heard as the debauchery and murders proceeded.”[11]

During the ceremonies of this cult, certain “wild women known as maenads, frenzied by music and wine, run barefoot over mountain and countryside, picking up snakes, and even tearing wild beasts apart with their bare hands. Almost tame by comparison are their companions, the horse-tailed, pig-eared satyrs, embodiments of bestial sexuality.”[12]

We are even told that the Greek historian and biographer “Plutarch was himself initiated into the Dionysiac mysteries.”[13]

Modern culture is no exception: theatre, movies, and music are still being part and parcel of the same cult—although, as we shall see in a different article, the new cult bears different names. Nearly all the Greek dramatists, poets, musicians, and philosophers knew about the cult:

“In the parody of his adversary’s choral songs Aeschylus summons the Muse of Euripides, whose presence he invokes in the most time-honoured manner; for the new-fangled songs, inspired by a Muse whom Dionysus does not hesitate to compare to a lewd woman from Lesbos, the lascivious movements of a castanet-player will prove more suitable than the traditional accompaniment of the lyre.

“Thus the contest between the two tragic poets turns more on the lyrics, both choral and “monodic,” than on the spoken parts. Any mention of the Muses’ art in archaic and classical Greece refers primarily to poetical forms which are sung and danced to an instrumental accompaniment.

“The contest is therefore well suited to an enquiry into the religious significance of the dramatic representations at the Great Dionysia and of the ritual performances which, by this mimetic intermediary, are transposed onto the stage, particularly in the choral parts of tragedy and comedy.

“Divinely inspired by the Muse, as is epic poetry, the melic choral compositions from which the songs of tragic and comic choruses derive present themselves from the enunciative point of view as song acts. Not only in its pragmatic, but often in its performative dimension, and in so far as it often forms part of a ritual celebration, the melic choral poem must be considered as a true cult act.

“That is to say that in tragedy, as in comedy or satyr drama, the generally choral melic forms brought to the theatre-sanctuary of Dionysus by the dramatization of a heroic or parodic action assume, from the religious point of view, a triple role:

“(a) they transpose into the orchestra of the theatron, by means of an entirely mimetic demonstration, the relation of the poet and the performers with the inspiring Muse, thus taking up and transforming the traditional forms of melic

poetry;

“(b) they mimic the ritual and cultic addresses to the gods which the dramatic action on stage requires; (c) they contribute indirectly, and particularly through the masks which the choreutai wear, to the celebration of Dionysus, the god celebrated on the occasion of the dramatic festivals.”[14]

“All-pervasive choral language makes it clear that there are no Dionysiac “initiations” without dance. Dionysus…speaks of having “introduced his choroi to barbarian lands” before he came to bring his teletai to the streets of Thebes “broad for dancing.”

Worshippers “honour Dionysus with dances,” the maenads are engaged in “secret choroi” during their “all night celebrations/ rites”…Central to this dance is the presence of the dancing god himself. The choros in the Bacchae certainly call on him to join their choros, as if only once Dionysus has appeared can the dance begin and is the worshippers’ mystic initiation completed.”[15]

In a similar vein, art historian Michael Tucker writes that intrinsic in primitive societies was the notion that music and shamanism were spiritually indistinguishable.[16]

In his classical work Dance and Ritual Play in Greek Religion, Steven H. Lonsdale

writes that “Dionysus…gives wine-induced manic dancing to mortals.”[17] Lonsdale further states: “Among the divine followers of Dionysus, dancing is the characteristic activity of the satyr as well as the maenad…That dancing is conceived as the quintessential activity of the Dionysiac thiasos is confirmed by vase inscriptions.”[18]

Michael Jackson is a perfect expression of this phenomenon. In 1993, Oprah Winfrey asked Jackson on her show why he always grabbed his crutch. Jackson responded, “It happens subliminally. It’s the music that compels me to do it. You don’t think about it, it just happens. I’m slave to the rhythm.”[19]

The ancient Greeks would have understood what Jackson said here, for the Muse “would often inspire possessed initiates, creating an ambiance of release and redemption.”[20]

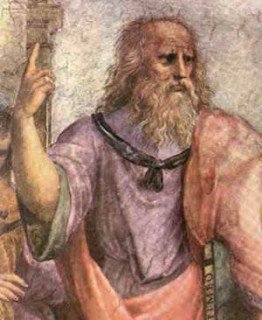

Consider what Plato says,

“The third type of possession and madness is possession by the Muses. When this seizes upon a gentle and virgin soul [of a poet] it rouses it to inspired expression in lyric and other sorts of poetry, and it glorifies countless deeds of the heroes of old for the instruction of posterity.

“But if a man comes to the door of poetry quite untouched by the madness of the Muses, believing that technique alone will make him a good poet, he and his sane compositions never reach perfection. They are instead utterly eclipsed by the performances of the inspired madman.”[21]

Again, our generation is not much different. Time magazine had this to say about Joni Mitchell:

“Joni Mitchell credits her creative powers to a ‘male muse’ she identifies as Art. He has taken so much control of not only her music, but her life, that she feels married to him, and often roams naked with him on her 40-acre estate. His hold over her is so strong that she will excuse herself from parties and forsake lovers whenever he ‘calls.’”[22]

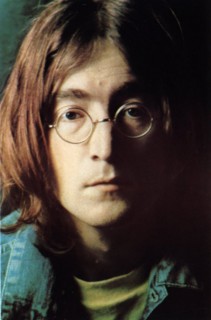

Glen Tipton of the band Judas Priest said in 1984, “I just go crazy when I go onstage…it’s like someone else takes over my body.”[23] This observation was echoed by Paul McCartney of the Beatles: “The music to ‘Yesterday’ came in a dream. The tune just came complete. You have to believe in magic. I can’t read or write music.”[24]

Yoko Ono added, “They [The Beatles] were like mediums. They weren’t conscious of all they were saying, but it was coming through them.”[25]

John Lennon himself said, “But my joy is when you’re like possessed, like a medium, you know. I’ll be sitting around and it’ll come in the middle of the night or at the time when you don’t want to do it—that’s the exciting part. So I’m lying around and then this thing comes as a whole piece, you know, words and music, and I think well, you know, can I say I wrote it? I don’t know who the [expletive] wrote it—I’m just sitting here and the whole [expletive] song comes out. So it, you’re like driven and you find yourself over on a piano or guitar and you put it down because it’s been given to you or whatever it is that you tune into.”[26]

Lennon continued, “I felt like a hollow temple filled with many spirits, each one passing through me, each inhabiting me for a little time and then leaving to be replaced by another.”[27] Lennon finally said, “It’s like being possessed. You try to go to sleep, but the song won’t let you. So you have to get up and make it into something, and then you’re allowed to sleep.”[28]

Listen to the Michael Jackson closely here:

“I wake up from dreams and go, ‘Wow, put this down on paper.’ The whole thing is strange. You hear the words, everything is right there in front of your face. And you say to yourself, ‘I’m sorry, I just didn’t write this. It’s there already.’ That’s why I hate to take credit for the songs I’ve written. I feel that somewhere, someplace, it’s been done and I’m just a courier bringing it into the world.”[29]

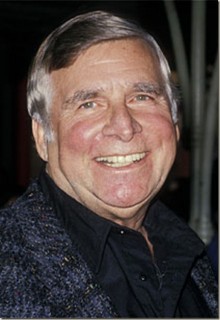

And this is not just happening in the world of rock and roll. The creation of the popular television series Star Trek came about in a similar way. Creator Gene

Roddenberry admits:

“What happens is that I bring [spirits] into this world, the world of humanity, and they take their place among them. Among us. They already exist. I just introduce them. That’s where the whole idea of Star Trek came from…I’m just a vehicle, a transporter.”[30]

James Cameron—who has written and directed such movies as Titanic, the Terminator series, the Alien series, and Avatar—got the idea for the movie Terminator, which established Cameron as a serious director and producer, in a similar fashion:

“The Genesis of The Terminator lay in the fever-induced images that Cameron experienced when he was in Rome during the post-production of Piranha 2. He later sketched the images that were burned into his consciousness during the dream, something he often does.

“‘The sketch was of a half Terminator, which actually looks pretty much like the finished one. He is crawling after a girl who is injured and cannot get up and run. The Terminator is pulling himself along using a kitchen knife, dragging a broken arm. It was really a horrific image.’

“This dream inspired Cameron to sit down and outline a screenplay about a robot hitman from the future. When he finally got back to Los Angeles and Piranha 2: The Spawning was completed, he was ready to move on to his next project.”[31]

Receiving messages from the spirit world in dreams is like going to night school for Cameron, and this represents the central background of nearly all of his films. Film critic Christopher Heard writes:

“Dreams play a key role in several of Cameron’s movies, and it is not uncommon for him to incorporate his own dreams into his screenplays. Cameron describes the relationship to his dreams this way: ‘Dreams, in general, are very important to me. I think they are as significant as any other part of our daily reality, and certainly part of our psychological process. And, personally, dreams have played a crucial role in my creative process.’”[32]

Once again, this phenomenon is not new. In his classic work Chapters in the History of Actors and Acting in Ancient Greece, scholar John Bartholomew O’Connor declared that “actors were generally called ‘artists or artists of Dionysus.’”[33] Scholar Joscelyn Godwin adds,

“[The gods] appear as messengers who have chosen human beings such as poets, charging them with a divine mission, at the same time leading their own life a little below the summit of Olympus, i.e., just the hierarchy of the gods. The implication of the Muses’ patronage of the arts, a theme so beloved in the Renaissance, is that the arts in their essence are no human invention but a gift of superhuman origin and inspiration, reflecting some form of universal knowledge and wisdom.”[34]

Nearly every serious Greek writer, philosopher, poet, actor, and musician knew about this. For example, consider what Socrates said:

“Good poets use no art at all, but are [all] inspired and possessed…These are not in their right mind when they make their beautiful songs, but they are then like Corybants [or Maenads], out of their wits and dancing about. As soon as poets rely upon their [Corybantic] harmony and rhythm, they become frantic and possessed, just like the Bacchante women, who are possessed and out of their senses…

“The poet is an airy thing, a winged and holy thing; and he [as a creative artist] cannot make poetry until he becomes inspired, when he goes out of his senses and no mind is left in him, [then creating] not by art, but by divine dispensation. Therefore, the only poetry that each one can make is what the Muse has pushed him to make…

“Therefore, God takes the mind out of the poets, and uses them as his [demented] servants. These beautiful poems are not human, are not made by man, but are instead divine and made by God. The poets are [therefore] nothing but the gods’ interpreters, possessed each one by whatever god it may be.”[35]

Moffitt writes: “In the Introduction to the Theogony (written ca. 750 BC), the ancient Greek poet Hesiod tells us how, while he was tending his flocks on Mount Helicon, the Muses had ‘breathed’ into him (or ‘inspired’ him with) the art of divine music.

“From the outset, the operations of inspiration were taken seriously by the Greeks…It was recognized, literally, to be a prophetic process arising from ‘ecstasy,’ literally signifying the act of ‘stepping out of one’s self.’ The highest form of ekstasis resulted in the transcendental union of the soul with the divinity, or One. At such luminal moments, one experiences apocalypsis, or an ‘uncovering.’

“The recognized Latin equivalent for an ‘apocalypse’ was revelation…The prophetic gift was, additionally, commonly spoken of as a kind of madness, or mania, for being an emotional condition sited outside of the bounds of ordinary

reason.[36]

Lillian Feder writes in his classic work Madness in Literature that there is evidence to suggest that elements and rituals of Dionysus can be found in the Mesolithic era, “when the chief activities of human beings were still hunting, fishing, and gathering…Farnell points out that Dionysus was ‘associated with the pasturing herds’ and with the ‘aboriginal pasture-god…Pan’ with whom Dionysus received ‘a common sacrifice’…in the borders of Argolis and Arcadia.”[37]

Classicist Martin Persson Nilsson adds, “In classical times the orgia of Dionysos are well known through many descriptions in the literature and through numerous works of art, both sculpture and vase paintings. Nor were they forgotten in the Hellenistic age, when in a milder form they were adapted to the public cult.”[38]

It was this Dionysus, writes classicist Ismene Lada-Richards, “who fired the imagination of poets and artists throughout antiquity and beyond.” Lada-Richard goes on to write:

“Being men’s ‘companion in festivity’ at symposia and drunken revelries alike; poured out to the rest of the Olympians at libations in every feast and festival of a polis’ sacred calendar; being the prototype of a state-actor’s dramatic transformations and the divine model for his experience of ‘getting out’ of himself; driving women to ‘ritual madness’ and binding them together in a feeling of ‘communion’ with his thiasos;

“Finally, ‘liberating,’ as Dionysus Lysios, the initiate in his mysteries from the fear of death, and promising to him or her a blissful afterlife, Dionysus is everywhere, an essential part of the everyday life, experience, and activities of the Athenian classical spectator. Furthermore, being the god who has left the most overwhelming and most wide-ranging record of evidence in the ancient world, Dionysus is firmly fixed in the cultural ‘encyclopedia’ of the everyday Greek spectator.

“And it cannot be emphasized too strongly that it is precisely through this ‘encyclopedia’ which accompanied, as it were, the audience into the theatre, that Dionysiac plays were viewed and mentally processed. In other words, the audience made sense of a stage-Dionysus not independently of but through and because of its ‘kept’ Dionysiac knowledge.”[39]

Literary scholar and classical writer Ernst Robert Curtius, known for his work

European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, admits:

“If we now look back at the Middle Ages, we can see that the theory of ‘poetic madness’—the Platonic interpretation of the doctrine of inspiration and enthusiasm—lived on through the entire millennium which extends from the conquest of Rome by the Goths to the conquest of Constantinople by the Turks.

“‘Lived on’ is perhaps too pretentious an expression. As it did with so many other coinages of the Greek spirit, the Middle Ages took this one [‘poetic madness’] from late Rome, preserved it, and copied it to the letter, until the creative Eros of the Italian Renaissance reawakened the spirit in the letter.

“That the poetic mania found a refuge in the medieval scriptoria, along with the rest of the authoritative stock of antique learning, is a paradox when one considers that it was precisely in the Middle Ages that writing poetry was considered to be sweat-producing labor and was recommended as such.”[40]

William Duff, writing during that period in his An Essay on Original Genius, proclaimed,

“A glowing ardor of Imagination is indeed the very soul of Poetry. It is the principal source of inspiration; and the Poet who is possessed of it, like a Delphian Priestess, is animated with a kind of divine fury.

“The intenseness and vigour of his sensations produce that enthusiasm of Imagination, which as it were hurries the mind out of itself; and which is vented in warm and vehement description, exciting in every susceptible breast the same emotions that were felt by the author himself.”[41]

This was clearly portrayed in the life of renowned poet William Blake. Of his work entitled “Milton,” he admitted: “I have written this Poem from immediate Dictation, twelve or sometimes twenty or thirty lines at a time, without Premeditation and even against my Will.”[42]

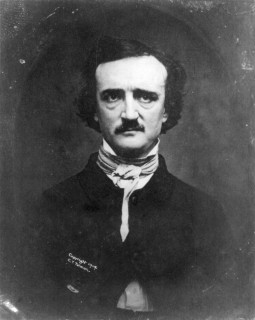

Legendary poet Edgar Allen Poe agreed with Blake, adding:

“Most writers—poets in especial—prefer having it understood that they compose by a species of fine frenzy—and ecstatic intuition—and would positively shudder at letting the public take a peep behind the scenes, at the elaborate and vacillating crudities of [creative] thought, at the cautious selections and rejections—at the painful erasures and interpolations—which, in ninety-nine cases out of the hundred, constitute the [real] properties of the literary histrio [or theatrics].”[43]

Neoclassicists such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann were cognizant of the fact that at some point they felt possessed while they were creating their craft. Winckelmann’s own signs of possession could hardly be dismissed:

“My breast seems to enlarge and swell with reverence, like the breast of those who were [formerly] filled with the spirit of prophecy. I feel myself transported [back in time] to Delos and into the Lycaean groves—places which Apollo honored by his presence.”[44]

Shelley stated, “Poetry is not like reasoning, a power to be exerted according to the determination of the will. A man cannot say ‘I will compose poetry.’ The greatest poet even cannot say it.”[45]

Rosamond E. M. Harding writes in An Anatomy of Inspiration,

“Byron, when sailing on the ship Hercules was asked by his friends to compose verses on the Austrian tyranny in Italy. He tried and failed. Turning to his friends he said: ‘You think it is as easy to write poetry as smoke a cigar—look, it’s only doggerel. Extemporizing verses is nonsense; poetry is a distinct faculty—it won’t come when called—you may as well whistle for the wind.”[46]

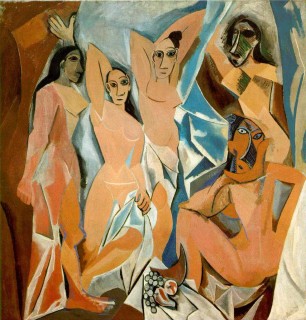

Far from being limited to music or poetry, these phenomena also affect art. Certainly Pablo Picasso would have agreed with Shelley and others here. Picasso credited his works, particularly Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, to an “affective ‘magical’ force.” Art historian Frances S. Connelly writes,

“Les Demoiselles incorporates the more horrific qualities of the monstrous and the idol. Les Demoiselles, for all its formal innovations that foreshadow the development of cubism, is a grotesque and frightening vision. The diabolical dream of [Paul] Gauguin has been transformed into a waking nightmare. The painting is a violent and aggressive statement of pure physicality…

“The figures confront the viewer with the iconic, horrific expression so central to the European conception of the idol. The aggressive sexuality of the Demoiselles forges an additional link with the grotesque tradition and with the characterization of idols.

“As classical beauty reflected rational order and intellectualized pleasure, the grotesque was, from satyrs and centaurs onward, associated with bestiality. Translated into Judeo-Christian iconography, the grotesques on cathedral facades were personifications of various forms of carnality.”[47]

In The Modern Mind: An Intellectual History of the 20th Century, Peter Watson quotes the artist himself:

“All alone in that awful museum, with masks, dolls made by the redskins, dusty manikins, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon must have come to me that very day, but not at all because of the forms; because it was my first exorcism-painting—yes, absolutely…The masks weren’t just like any other pieces of sculpture. Not at all. They were magic things…

“The Negro pieces were intercesseurs, mediators; ever since then I’ve known the word in French. They were against everything—against unknown, threatening spirits…I understood; I too am against everything. I too believe that everything is unknown, that everything is an enemy!…

“All the fetishes were used for the same thing. They were weapons. To help people avoid coming under the influence of spirits again, to help them become independent. They’re tools. If we give spirits a form, we become independent. Spirits, the unconscious…, emotion—they’re all the same thing. I understood why I was a painter.”[48]

Modern entertainers and the Muses

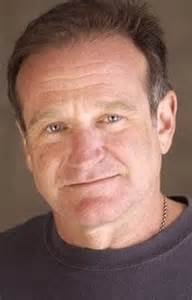

Here’s how Robin Williams described some of his best performances: “Yeah! Literally, it’s like possession—all of a sudden you’re in…you just get this energy that just starts going…In the old days you’d be burned for it…But there is something empowering about it.”[49]

Denzel Washington agrees: “Basically what I did was I got on my knees and sort of communicated with the spirits. And when I came out, I was in charge.”[50]

John Lennon again declared: “When the real music comes to me…[it] has nothing to do with me, ‘cause I’m just the channel. The only joy for me is for it to be given to me, and transcribe it like a medium.”[51]

Anthropologist Maria Teresa Velez writes:

“The state of possession is supported by music. Music and dance are essential elements in virtually every ritual, where most of the liturgical procedures involve chanting, drumming, and dancing.

“Movement accompanied by drumming becomes a channel of access to the world of the orichas [possession]. Thus, the drums used during these ceremonies, the bata drums, are attributed the power to talk to the deities, inviting and enticing them to descend on their children.”[52]

In other words, no drums, no ritual ceremonies. Can you imagine rock and roll and rap music without drums or percussion instruments, where in many instances the rhythm overpowers the melody and harmony?

It was Plato who said in The Republic that

“Through foolishness they [the people] deceived themselves into thinking that there was no right or wrong in music—that it was to be judged good or bad by the pleasure it gave. By their work and their theories they infected the masses with the presumption to think themselves adequate judges. … As it was, the criterion was not music, but a reputation for promiscuous cleverness and a spirit of law-breaking.”

Because of its revolutionary potency (for good or bad), Aristotle himself wanted music to be regulated by the state.

The Church, like it or not, knew that there is a logos in music, which keeps melody, harmony, and rhythm in perfect balance. Whenever the in particular rhythm overpowers both the melody and harmony, then music becomes anti-logos in its metaphysical sense. And philosophers from Plato to Nietzsche knew this very well.[53]

And that this lower logos has to reflect the higher Logos, who the Church views as Christ incarnate. Classical music essentially represents that logos in its intellectual and harmonic nature. It is no coincidence that most classical composers and artists during the medieval period, the Renaissance era, the Baroque and classical periods, were essentially Christians or were working within a Christian framework.

Those were great periods in Europe and the fruit of those periods continues to be a blessing to all mankind. Who doesn’t enjoy the music of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Liszt, etc? Who doesn’t enjoy Leonardo’s Last Supper? (Don’t get distracted by Dan Brown’s bogus The Da Vinci Code.)

The Anti-Thesis of True Music

In contrast, Rap and rock and roll are the anti-thesis true logos, and it is no coincidence that both have been used as revolutionary and subversive engines to bring about vast social changes among the youth.

Since Jewish revolutionaries deny metaphysical logos, it was no coincidence that nearly all the major rock and rap groups had Jewish revolutionary supporters or Jewish musicians or Jewish managers and companies. Now, in order to really succeed in Hollywood, non-Jews have to act a certain way. British journalist William Cash wrote:

“Bill Stadiem, a former Harvard educated Wall Street lawyer who is now a screenwriter in LA, told me that he recently came across an old WASP friend in an LA restaurant who had been president of the Porcellian at Harvard—the most exclusive undergraduate dining-club.

“His friend—a would-be producer—was dressed in a black nylon tracksuit and had gold chains on his wrist; dangling around his neck was a chunky Star of David. Stadiem asked: ‘Why the hell are you dressed like that?’ The WASP replied: ‘I’m trying to look Jewish.’”[54]

This is a huge topic but it will not be discussed until late fall. It is time to return to Snowden, the NSA, and the Zionist regime. Then we’ll move on to the article “God and the Intellectuals.” Next will be the history and dark side of Christian Zionism, and finally the history of usury and exploitation.

(New York: Pocket Books, 1996), 59; emphasis added.

Jonas E. Alexis has degrees in mathematics and philosophy. He studied education at the graduate level. His main interests include U.S. foreign policy, the history of the Israel/Palestine conflict, and the history of ideas. He is the author of the new book Zionism vs. the West: How Talmudic Ideology is Undermining Western Culture. He teaches mathematics in South Korea.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy