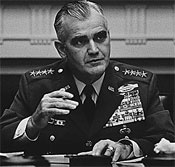

William Westmoreland, the son of a prosperous textile manufacturer, was born in Spartanburg County, South Carolina, on 26th March, 1914. He graduated from West Point in 1936 and during the Second World War commanded artillery battalions in Sicily and North Africa. Later he became Chief of Staff of the 9th Infantry Divisions.

William Westmoreland, the son of a prosperous textile manufacturer, was born in Spartanburg County, South Carolina, on 26th March, 1914. He graduated from West Point in 1936 and during the Second World War commanded artillery battalions in Sicily and North Africa. Later he became Chief of Staff of the 9th Infantry Divisions.

Westmoreland commanded the 187th Airbourne Infantry in the Korean War . He was also commander of the 101st Airborne Division and at the age of 42 became the youngest major general in the United States Army.

In 1960 Westmoreland was appointed superintendent of West Point in 1960. Four years later In June 1964 he became the senior military commander of United States forces in Vietnam. In this post he played an important role in increasing the number of U.S. soldiers fighting in the Vietnam War.

In 1965, Westmoreland developed the aggressive strategy of ‘search and destroy’. The objective was to find and then kill members of the National Liberation Front. The US soldiers found this difficult. As one marine captain explained: "You never knew who was the enemy and who was the friend. They all looked alike. They all dressed alike." Innocent civilians were often killed by mistake. As one Marine officer admitted they "were usually counted as enemy dead, under the unwritten rule ‘If he’s dead and Vietnamese, he’s VC’."

Westmoreland was determined to avoid the kind of disaster suffered by the French Army at Dien Bien Phu . He therefore forbade any military operations by units smaller than about 750 men.

In September, 1967, the NLF launched a series of attacks on American garrisons. Westmoreland was delighted. Now at last the National Liberation Front was engaging in open combat. At the end of 1967, Westmoreland was able to report that the NLF had lost 90,000 men. He told President Lyndon B. Johnson that the NLF would be unable to replace such numbers and that the end of the war was in sight.

Every year on the last day of January, the Vietnamese paid tribute to dead ancestors. In 1968, unknown to the Americans, the NLF celebrated the Tet New Year festival two days early. For on the evening of 31st January, 1968, 70,000 members of the NLF launched a surprise attack on more than a hundred cities and towns in Vietnam. It was now clear that the purpose of the attacks on the US garrisons in September had been to draw out troops from the cities.

The NLF even attacked the US Embassy in Saigon. Although they managed to enter the Embassy grounds and kill five US marines, the NLF was unable to take the building. However, they had more success with Saigon’s main radio station. They captured the building and although they only held it for a few hours, the event shocked the self-confidence of the American people. In recent months they had been told that the NLF was close to defeat and now they were strong enough to take important buildings in the capital of South Vietnam. Another disturbing factor was that even with the large losses of 1967, the NLF could still send 70,000 men into battle.

The Tet Offensive proved to be a turning point in the war. In military terms it was a victory for the US forces. An estimated 37,000 NLF soldiers were killed compared to 2,500 Americans. However, it illustrated that the NLF appeared to have inexhaustible supplies of men and women willing to fight for the overthrow of the South Vietnamese government.

Westmoreland was replaced by General Creighton W. Abrams in 1968. On his return to the United States he was appointed as Chief of Staff to the United States Army.

William Westmoreland retired in 1972. A member of the Republican Party, Westmoreland was unsuccessful in 1974 in his attempt to become governor of South Carolina. His memoirs, A Soldier Reports, was published in 1980.

n 1947, he married Katherine (Kitsy) Stevens Van Deusen. They had three children: two daughters Katherine Westmoreland, and Margaret Westmoreland; and one son named James Ripley Westmoreland.

William Westmoreland died on July 18, 2005 at the age of 91 at the Bishop Gadsden retirement home in Charleston, South Carolina. On July 23, 2005, he was buried at the West Point Cemetery, United States Military Academy.

Related Article: Westmoreland: A Hero in His Own Mind – a Critical Analysis of General Westmoreland’s Career – by Vietnam Veteran Gordon G. Duff

Vietnam War – Gen. William Westmoreland

Time Magazine Man of the Year – 1965: William C. Westmoreland

Jan. 7, 1966

Nothing is worse than war? Dishonor is worse than war. Slavery is worse than war. –Winston Churchill To the quickening drumfire of the fighting in South Vietnam, Americans sensed early in 1965 that they might have to choose between withdrawal or vastly greater involvement in the war. By year’s end, it was clear that the U.S. had irrevocably committed itself the nation’s third major war in a quarter- century, a conflict involving more than 1,000,000 men and the destiny of Southeast Asia.

It was a strange, reluctant commitment. As the small, far- off war grew bigger and closer, it stirred little of the fervor with which Americans went off to battle in 1917 or 1941. The issues were complex and controversial. The enemy was no heel- clicking junker or sadistic samurai but a small, brown man whose boyish features made him look less like the oppressor than the oppressed. The U.S. was not even formally at war with him. Nor at first could Americans be sure than divided, ravaged South Viet Nam had the stomach or stability to sustain the struggle into which it had drawn its ally.

The risk and the responsibility for the war were, of course, Lyndon Johnson’s. "We will stand in Viet Nam," he said in July. Thereafter, the President moved resolutely to make good that pledge, weathering open criticism from within his own party, strident protest from the Vietnik fringe, and the disapprobation of friendly nations from the Atlantic to the China Sea.

All No Man’s Land. It fell to the American fighting man to redeem Johnson’s pledge. Plunged abruptly into a punishing environment, pitted against a foe whose murderously effective tactics had been perfected over two decades, the G.I. faced the strangest war at all.

Professing to scorn the U.S. as a paper tiger, Communist China had long proclaimed Americans incapable of combat under such conditions–while prudently allowing North Viet Nam to fight its "war of liberation." The Americans turned out to be tigers, all right–live ones. With courage and a cool professionalism that surprised friend and foe, U.S. troops stood fast and firm in South Viet Nam. In the waning months of 1965, they helped finally to stem the tide that had run so long with the Reds.

As commander of all U.S. forces in South Viet Nam, General William Childs Westmoreland, 51, directed the historic buildup, drew up the battle plans and infused the 190,000 men under him with his own idealistic view of U.S. aims and responsibilities. He was the sinewy personification of the American fighting man in 1965 who, through the monsoon mud of nameless hamlets, amidst the swirling sand of seagirt enclaves, atop the jungled mountains of the Annamese Cordillera, served as the instrument of U.S. policy, quietly enduring the terror and discomfort of a conflict that was not yet a war, on a battlefield that was all no man’s land.

20-Year Problem. In the process, American troops gave an incalculable lift to South Viet Nam’s disheartened people and divided government. And, important as that was, they helped preserve a far greater stake than South Viet Nam itself. As the Japanese demonstrated when they seized Indo-China on the eve of World War II, whoever holds the peninsula holds the gate to Asia. Were Hanoi to conquer the South and unify it under a Communist regime, Cambodia and Laos would tumble immediately. After that, the U.S. would be forced to fight from a less advantageous position in Thailand to hold the rest of Southeast Asia. "If you lose Asia," says General Pierre Gillois, a celebrated French strategist, "you lose the Pacific lake. It is an extraordinary problem, the problem of the next 20 years."

Lyndon Johnson had waited dangerously long before acting on the problem. Thereafter, for all his repeated declarations that the U.S. would sit down and talk "with any government at any place at any time," despite even last week’s multiplicity of peace missions, the President moved swiftly and unstintingly toward its solution. With all the resources available to the world’s most powerful nation, Johnson established beyond question the credibility of the U.S. commitment to Asia.

No Sanctuary. The troops under William Westmoreland did more. "If the other guy can live and fight under those conditions," said the general, "so can we." In baking heat and smoldering humidity of the Asian mainland, the American applied their own revised version of the guerrilla-warfare manual that Communists from Havana to Hanoi had long regarded as holy writ. With stupendous firepower and mobility undreamed of even a decade ago, U.S. strike forces swooped into guerrilla redoubts long considered impenetrable. Like clouds of giant dragonflies, helicopters hauled riflemen and heavy artillery from base to battlefield in minutes, giving them the advantages of surprise and flexibility. Tactical air strikes scraped guerrillas off jungled ridges, buried them in mazelike tunnels, or kept them forever on the run. Unheard from the grounds, giant B-52s of the Strategic Air Command pattern-bombed the enemy’s forest hideaways, leaving no sanctuary inviolable.

Whatever the outcome of the war, the most significant consequence of the buildup is that, for the first time in history, the U.S. in 1965 established bastions across the nerve centers of Southeast Asia. From formidable new enclaves in South Viet Nam to a far-flung network of airfields, supply depots and naval facilities building in Thailand, the U.S. will soon be able to rush aid to any threatened ally in Asia. Should the British leave Singapore, as they may do by the 1970s, the new U.S. military complex would constitute the only Western outpost of any consequence from the Sea of Japan to the Indian Ocean.

The U.S. presence will also have a beneficent impact on the countries involved. The huge new ports that are being scooped out along the coasts of Viet Nam and Thailand should permanently boost the economies of both nations. Vast, U.S.- banked civilian-aid programs are aimed at eradicating the ancient ills of disease, illiteracy and hunger.

Small Windows. Recently, Peking has made it a point to proclaim its delight at the prospect of the U.S.’s depleting its resources on a major land war in Asia. That prospect may seem less pleasing today. Where the Communists almost had victory within their grasp last spring, the U.S. now bars the way and stands ready to repel any other attempted aggression. Unless Peking and Hanoi withdraw from South Viet Nam–and lose face throughout Asia–it is the Communists themselves who risk being bogged down in wars that they can neither afford nor end.

Plainly, neither China nor North Viet Nam reckoned on full- scale U.S. intervention in Viet Nam. Their blunder came as no surprise to Westmoreland. "They look out upon the rest of the world, and of America in particular, is what they want it to be."

A Kill at the Waist. At the beginning of 1965, the view from Hanoi’s windows must have been rosy indeed. From a force of fewer than 20,000 at the end of 1961, the Viet Cong had grown to a lethally effective terrorist army of 165,000 whose supplies, orders and reinforcements flowed freely from the North. Viet Minh regulars were infiltrating at the rate of a regiment every two months. From the tip of Ca Mau Peninsula to the 17th parallel, huge swaths of the South lay under Communist sway, and with good reason: in that year, the Viet Cong had kidnapped or assassinated 11,000 civilians, mostly rural administrators, teachers and technicians.

Saigon’s army, which since 1954 has been trained by U.S. advisors almost entirely to repel a conventional invasion from the North, was seldom a match for the guerrilla cadres. The Communists were confident that they could sever the South at its narrow waist in the Central Highlands. After that, victory would be just a matter of time.

The U.S. gave them little cause of doubt. All thorough the 1964 presidential campaign, while Barry Goldwater called for bombing raids in the North, it was Lyndon Johnson’s unruffled position that the U.S. was already doing all it should to keep the South afloat. After his landslide election, the President became so engrossed in the Great Society that little Saigon seemed all but forgotten. Asia rated only 126 words in the State of the Union message that ran on for 5,000.

Changed Rules. When the U.S. finally acted, it was almost a classic case of too little, too late. What finally stirred Lyndon’s choler was the Viet Cong attack on two U.S. camps at Pleiku in February. Eight Americans died, 125 were wounded. "I’ve had enough of this," raged the President. Next day the scores of U.S. Navy jets roared beyond the 17th parallel for the first time to plaster "bloodless" military installations in North Viet Nam. In return, the Viet Cong blew up a U.S. enlisted men’s billet in the port city of Qui Nhon. This time the U.S. and South Viet Nam replied with a joint 160-plane raid.

Abruptly, the ground rules had changed. Some 3,500 combat marines from Okinawa landed to secure Danang Airbase. Advance units of the 173rd Airborne also streamed in. One of the most significant U.S. moves was to assign U.S. planes to bomb and strafe Viet Cong units in South Viet Nam itself.

Starting in late May, 100,000 U.S. servicemen were funneled into Viet Nam in 120 days. Warships from Task Force 77, the assault unit of the Seventh Fleet launched round-the-clock bombing raids, trained their six-inch guns on Viet Cong concentrations as far as 15 miles inland. Giant Guam-based B-52s of the Strategic Air Command began blasting forested guerrilla redoubts. U.S. medium bombers inched ever closer to the Red Chinese frontier in their raids against the North.

"Maximum Deterrence." The Viet Cong also intensified their war. As the summer monsoons neared, they switched increasingly to the battalion- and regiment-sized attacks that, by the doctrines of Mao Tse-tung and North Viet Nam’s General Vo Nguyen Giap, are needed to finish a guerrilla war. Two full Communist regiments overran a Special Forces fort at Dong Xoai, 55 miles north of Saigon, decimating three Vietnamese battalions in the war’s biggest battle. The guerrillas seemed to be everywhere–and in strength. A full regiment overran Ba Gia; another annihilated a Vietnamese battalion in Binh Duong province; a third captured the town of Dak Sut; U.S. Special Forces defenders were bloodied at Bu Dop and Duc Co. Talk of neutralism began to stir the cities of the South as the fledgling military regime of Air Vice Marshal Nguyen Cao Ky–the tenth Saigon government since Ngo Dinh Diem’s assassination in November 1963–shakily took power in June.

Acting on Westmoreland’s urgent plea for more combat troops and planes, the President in July spent eight days in secret conferences before adopting a cautious program of "maximum deterrence" calculated not to unduly alarm Hanoi’s friends in Moscow. For the first time in any comparable emergency, the Administration did not order economic controls or mobilized reserves. Monthly draft calls were doubled to 235,000. The armed forces were authorized an additional 340,000 men for a total of 2,980,000. Most important of all, reinforcements were rushed to Viet Nam.

Main Artery. Even the sounds and sights of the land soon changed as U.S. deuce-and-a-halfs, Jeeps, bulldozers, helicopters and fighter aircraft raised whirlwinds of cinnamon- colored dust and sand as white as snow. In the north, some 45,000 marines clustered around Hue, Danang and Chu Lai. The new 1st Cav settled at An Khe, just off Route 19, main artery leading to the beleaguered Central Highlands. Qui Nhon, Route 19’s eastern terminus, was held by South Korea’s crack 15,000- man Capital Division.

At pristine Cam Ranh Bay, where czarist Russia’s fleet took shelter just before its crushing defeat by the Japanese navy in 1905, combat engineers turned the natural harbor into a major port. Twenty miles down the coast, the "Screaming Eagles" of the 101st Airborne Brigade began operating as a mobile strike force. In the guerrilla-infested jungles around Saigon prowled the 1st Infantry Division ("Big Red One"), the 173rd Airborne, a 1,200- man battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment, a 250-man New Zealand artillery unit.

Water Through a Rag. Some of the marines barely had time to pitch their tents when they were sent into their first major battle. On a peninsula below Chu Lai, 5,000 marines, aided by rocket-firing Cobra helicopters, jet fighters and naval guns from Task Force 77, killed close to 700 guerrillas. But this, they soon learned, was Viet Nam. No sooner did Operation Starlight end, said an exasperated officer, than the surviving Viet Cong "seeped back in like water through a wet rag."

Not until the Communists began concentrating troops in the Central Highlands was there another battle of Starlight’s scope. Worried that their supply routes might be in danger, 6,000 Viet Minh and Viet Cong on Oct. 19 pounced on a Special Forces camp manned by 400 montagnard tribesmen and twelve U.S. advisors at Plei Me, near where the Ho Chi Minh trail snakes out of Laos and Cambodia into South Viet Nam. But for 600 sorties that littered the camp’s perimeter with Viet Minh dead, Plei Me would almost certainly have fallen. It was not the first time that air strikes saved the day. "The ground troops keep telling us that we are saving their necks." says Air Force Colonel James Hagerstrom, boss of the bustling Tactical Air Coordination Center at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut Airport. As it was, the Communists broke off their siege of Plei Me after nine days and 850 dead.

"Come & Get It." A 1st Cav brigade set out immediately in pursuit of the retreating Reds to check out intelligence reports that seven and possibly nine 2,000-man regiments were assembling in the highlands. "I gave them their head," recalls Westmoreland, "and told them their mission was to pursue and destroy the enemy." In the foothills of the Chu Pong massif, practically in Cambodia’s back yard, the brigade found its quarry. Helilifted to a spot called Landing Zone X Ray, a battalion of cavalrymen found itself smack in the middle of the 66th North Vietnamese regiment. One platoon was cut off on a ridge and badly mauled. Two others were lured into a trap and wiped out; some of the U.S. wounded were shot or decapitated and at least one was left hanging head down from a tree.

The division’s artillery saved the day, pouring more than 8,000 rounds into Viet Minh ranks, while strafing jets hemstitched whole rows of assaulting Communists. SAC B-52s from Guam provided tactical support in ten thunderous raids. The battle of Chu Pong was over–but another was about to begin.

Moving out of the mountains and across the Ia Drang Rover, 500 troops walked through prickly elephant grass into a Communist ambush. From three sides, Viet Minh hard-hats rained mortar, rocket and small-arms fire on the troops. Shouting "G.I. son of a bitch!," they sprang from behind hedgerows and trees, giant anthills and bushes to take on the American in savage hand-to-hand fighting. The cavalrymen hollered right back, "Come on Charlie, come and get it!" The Reds, their flanks raked by strafing fire and napalm, finally retreated.

In the two battles, the Communists lost more than 1,200 men. US. casualties–2240 dead, 470 wounded–were the worst of the war, higher than the Korean War’s weekly average of 210 combat deaths. Costly as it was, Westmoreland calls it "an unprecedented victory" in the struggle for South Viet Nam. He says proudly: "At no time during the engagement were American troops forced to withdraw or move back from their positions except for purposes of tactical maneuver."

Phoenix-Like. Despite the loss of 7,000 men in seven weeks, the Communists have displayed what one U.S. officer calls a "phoenix-like ability" to recuperate. To speed the flow of infiltrators, at least three new roads have been hacked through the Laotian panhandle and some 10,000 Viet Ninh guards assigned to keep them open. Down the trails, often concealed from the air by a solid canopy of 150-ft. trees, move trucks, elephant and wiry porters capable of toting 30-lb. loads 15 miles a day.

Most of the Communist reinforcements are concentrating in such plateau provinces as Kontim and Pleiku, where the only fire brigade at Westmoreland’s disposal has been the overworked 1st Cavalry. To lend them a hand a 4,000-man contingent from the Army’s 25 Infantry Division was dispatched by air from Hawaii last week.

Westmoreland foresees a long war and is determined to be on hand for as much of it as possible. While two years is the normal tour for top U.S. officers in Viet Nam, he has asked to stay on here after his time is up this month. "The job isn’t over yet," he says, "and unless it was beyond my control, I have never left any job that I hadn’t finished. I have no intention of breaking that rule now."

No Gimmicks. There is an almost machinelike singlemindedness about him. His most vehement cuss words are "darn" and "dad-gum." A jut-jawed six-footer, he never smokes, drinks little, swims and plays tennis to remain at a flat- bellied 180 lbs.–only 10 lbs. over his cadet weight. Says Major General Richard Stilwell, commander of the U.S. Military Advisory Group in Thailand: "He has no gimmicks, no hand grenades or pearl-handled pistols. He’s just a very straightforward, determined man." Few who know him doubt that he will some day be Army Chief of Staff.

Westmoreland belongs to the age of technology–a product not only of combat but also of sophisticated command and management colleges from Fort Leavenworth to Harvard Business School. The son of a textile-plant manager in rural South Carolina, Westmoreland liked the cut of a uniform from the time he was an Eagle Scout. Though he never made the honor roll at West Point, he was first captain of cadets (class of ’36) and won the coveted John J. Pershing sword for leadership and military proficiency.

As a young artillery officer, Westmoreland worked out a new logarithmic fire-direction and control chart that is still in use. During World War II he got a chance to try it out as commander of an artillery battalion in North Africa and Sicily. During ten months of front-line combat from Utah Beach to Elbe, he had two bouts of malaria and a brush with a land mine that blew a truck out from him but left him almost unscathed.

No Mischief. Volunteering for Korean duty in 1952, Westmoreland went over as commander of the tough 187th Regimental Combat Team, made a couple of paratroop jumps before the armistice was signed. Fretful that the cease-fire was playing havoc with his men’s discipline, Westmoreland set them a spartan regimen: reveille at 5, a two-mile run, digging fortifications all day, baths in an icy creek and, after dinner, 2 1/2 hours of intramural sports, especially boxing. "By 10 o’clock every night," grins Westmoreland, "they were so exhausted they couldn’t make mischief of any kind."

After a round of Pentagon assignments, he became the Army’s youngest major general at 42. Named superintendent of West Point in 1960, he expanded its facilities, increased enrollment (from 2,500 to 4,000) and came under congressional fire for the first and–so far–only time in his career. His offense was to hire Football Coach Paul Dietzel away from Louisiana State University, and the Louisiana delegation was fighting-mad. In 1964, "Westy" was summoned to Saigon as Paul Harkins’ deputy. By midyear he was the Pentagon’s natural choice for the top job–and a fourth star–when Harkins returned to the U.S.

More Hats than Hedda. In the command he inherited, Westmoreland wears more hats than Hedda Hopper. He has the politically sensitive job of top U.S. advisor to South Viet Nam’s armed forces and boss of the 6,000-odd U.S. advisors attached to the Vietnamese units. As commander of Military Assistance Command. Viet Nam (MAC-V), he has under him all U.S. servicemen–115,000 soldiers, 10,000 sailors, 17,500 airmen, 4,000 marines, 250 coast guardsmen–in the country. More than 1,000 Army helicopters and light aircraft are his responsibility, as well as some 550 U.S. Air Force planes–soon to be increased to 1,200–a Navy seadrome at Cam Ranh Bay.

Outside his direct area of responsibility, but closely responsive to his needs are two other sizable forces: 1) the 150 warships and 70,000 men of the Seventh Fleet in station in the South China Sea, and 2) the mushrooming U.S. military establishment in Thailand, with seven fighter squadrons, 12,000 men, and more on the way. To supply them, the U.S. is not only building facilities at Sattahip on the Gulf of Siam, but has also laid in a storage area at Korat with enough supplies to outfit a combat brigade–just in case Red China makes good its threat to stir trouble in Thailand’s northeast. Thai-based U.S. planes are already operating out of Udorn, Ubon, Takhli and Nakhon Phanom to blast Red infiltration routes through Laos, bomb North Viet Nam, and conduct rescue missions for downed U.S. pilots.

Work Like the Devil. To keep this vast establishment operating, Westmoreland heeds–and invariably exceeds–the advice he gave newcomers to Viet Nam: "Work like the very devil. A seven-day, 60-hour week is the very minimum for this course." Rising at 6:30 in his two-story French villa, Westmoreland does 25 push-ups and a few isometric exercises, usually breakfasts alone (his family, along with 1,800 other dependents, was ordered out of the country by the President last February, is now in Honolulu). At his desk by 7:30, he rarely leaves it before nightfall, even then lugs home a fat briefcase. "He’s a man who simply can’t quit working," says an officer who has served three times with him. At least two days a week he zips around the field by Beechcraft U-8F and helicopter, often galloping to and from his craft at a dead run so that he can squeeze in one more visit to one more outpost in the "boonies."

General Westmoreland tries valiantly to meet as many of his men as he possibly can. Wherever he goes, he reminds them that Viet Nam is not only a military operation, but a "political and psychological" struggle as well "In this war," says Major General Lewis W. Walt, who reports to Westmoreland as Marine Commander in Viet Nam, "a soldier has to be much more than a man with a rifle or a man whose only objective is to kill. He has to be part diplomat, part technician, part politician–and 100% a human being." In a war in which the kindly-looking peasant often turns out to be a gun-toting guerrilla, that can be a tall order. Snapped a marine private: "We try to help those goddamn people and you know what they do? They send in their kids to steal our grenades and ammunition and use them to kill us. The hell with them!"

Golden Fleece. Yet, as it has done everywhere else, the G.I.’s heart inevitably goes out to war’s forlorn victims. Marvels a Viet Nam veteran in the Pentagon: "Imagine a really gung-ho West Point officer worrying about growing corn for peasants!" Westmoreland, who is so gung-ho a West Pointer that he looks well-pressed in swimming trunks, does worry. "Today’s soldier," he says, "must try to give, not take away,"

In Operation Golden Fleece last fall, he’d employed 10,000 marines throughout northern paddyfields to give Viet Nam peasants the most valuable present of all–security to harvest and sell their corps without interference. One result was that the Viet Cong had to boost their 10% "rice tax" on farmers to 60% in unprotected areas, with no rise in their popularity rating. More often, the G.I.’s effort is spontaneous. At Phu Bai, marines organized scrub-ins for the village toddlers. Army Captain Ronald Rod, before he was killed by a Viet Cong sniper in December, collected enough money and supplies to get an orphanage started by writing to a New Orleans newspaper. On his own initiative, Navy Medic "Doc" Lucier, a burly, open-faced Negro from Birmingham, Ala., braves booby- trapped trails to give shots, distribute drugs and administer first-aid in out-of-the-way villages. There’s just got to be something more than bullets," he says. "Until we start treating these people like human beings, they aren’t going to want to help us."

43 Battles. Under a more formal program, more than 1,000 experts with the U.S. Operations Mission are distributing more than $500 million a year in economic assistance, training civil servants in a dozen Saigon ministries and advising local officials. USOM in the past five years has helped build 4,682 classrooms, drill 1,900 fresh-water wells, set up 12,000 village health clinics and establish 718 factories. In 1965 alone, it brought 7,000,000 textbooks, and later this month will inaugurate television networks designed to reach–and help unify–close to half of the country’s 15 million people. As the AID men see it, they are fighting "43 separate battles in the Viet Cong"–one in every province–and each is a touch- and-go affair. For the man behind the water buffalo, security is all; his allegiance belongs to whichever side can give it to him.

What the Vietnamese need most is at least 20,000 more trained administrators to run each district after it has been won by soldiers. Without them, says a U.S. officer, "we can take ground, but we can’t hold it."

Blindman’s Buff. At every level, the U.S. is locked in a complex, unpredictable–and brutal–struggle. Last month three U.S. marines and eight South Vietnamese captured by the Viet Cong on a patrol 80 miles southwest of Danang were savagely executed. One American was shot six times in the face at close range. Another’s face was hacked beyond recognition with a machete.

In many ways, it is the same kind of fighting–with some local refinements–that G.I.s faced in the island-hopping battles of World War II. It is and interminable blindman’s buff that has squads and platoons snaking steadily along tangled jungle paths, ever fearful of snipers’ bullets, ever watchful for the trip wire that might set off a lethal "Bouncing Betty" mine or drive poison-tipped stakes into a man’s chest. The big set-piece battles–Chu Lai and Plei Me, Chu Pong and Ia Deang–were the exceptions, and even they rarely involved more than a regiment on each side.

Ninth Circle. When he was not under fire, the U.S. fighting man was enduring living conditions that would have made Dante’s ninth circle seem cozy. He was mired in mud when it rained, choked by dust when it did not. There were leeches and lice, poisonous vipers and venereal disease, dengue, and a virulent strain of malaria that has defied preventatives and resists cure. Temperatures hit 130 degrees on the sandy beaches, 20 degrees in the mountains. In the water-filled bunkers of Danang and Phan Rang, marines and paratroopers wrapped themselves in rubberized ponchos to grab a few hours’ soaked sleep. In the endless paddyfields, man on long patrols came down with agonizing foot sore from polluted ooze.

"Everything rusts or mildews," complained Navy Lieut. Commander Richard Escajeda, head surgeon of the marines’ "Charlie Med" hospital at Danang. "The sterilized linen never dries. Bugs crawl into our surgical packs. Mud is everywhere." An earthier–or muddier–protest came from a jungle-hardened trooper in the 1st Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment, bivouacked with the U.S. 173rd Airborne Brigade. "Ya know, I been here for six weeks, and for five of ’em I’ve never been dry," he lamented. "If a man ain’t wet with sweat, he’s drenched with rain. Me clothes are rottin’ and me boots are fallin’ apart."

Boiling Ants. In this dark, watery world, the enemy lurks like a predatory pike, seldom visible, forever poised for the kill. Both the black-pajamaed guerrilla and the khaki-uniformed Viet Minh regular from the North have become increasingly sophisticated and determined fighters. At Ia Drang, Major General Harry W.O. Kinnard, commander of the Army’s 1st Calvary Division (Airmobile), marveled at the way the Viet Minh hard- hats "came boiling off those hills like ants and pushed their attack right through our artillery, tactical air and small-arms fire–in broad daylight. It was eloquent testimony that this war is a tough one."

Though not always as aggressive as their comrades from the North, the Viet Cong guerrillas have been around for so long that they know every thicket and clump of elephant grass for miles around. Kinnard told of a conversation his men had monitored on the V.C. radio network. "All right," a Viet Cong company commander told a subordinate, "I want you to move down to that place where we laid an ambush for the French twelve years ago."

4-to-1 Ratio. By the end of 1966, U.S. strength is expected to reach 400,000–nearly as big as an army as the French had in all Indo-China, and with infinitely superior equipment. Buoyed by the U.S. effort, South Viet Nam is simultaneously strengthening its armed forces by 10,000 men a month, should muster 750,000 fighting men by the end of 1966.

The Communists in turn are increasing their 250,000-man first-line force by up to 7,000 a month–4,500 by infiltration from the North, and rest by forced drafts in Viet Cong- controlled villages–and by December had at least 80,000 more men in the South than they had when the year began.

By spring, the allies should outnumber the enemy 4 to 1–far less than the nearly 10-to-1 superiority that Britain’s General Sir Gerald Templer enjoyed in Malaya’s twelve-year guerrilla war, but sufficient for them to take the initiative. Once that happens, said a U.S. official, "we can begin pacification and the tide will begin to turn."

Building & Fighting. Pacification, in the long run, is Westmoreland’s greatest challenge. "Viet Nam is involved in two simultaneous and very difficult tasks," he says. "Nation building, and fighting a vicious and well-organized enemy. If it could do either alone, the task would be very simplified, but its got to do both at once. A political system is growing. It won’t, it can’t reach maturity overnight. Helping Viet Nam toward that objective may very well be the most complex problem ever faced by men in uniform anywhere on earth."

It is a challenge such as no major nation has ever faced before. The great powers of the past were, first and last, empire builders hungry for territory and treasure. The U.S. seeks neither. The richest nation in history (its GNP has more than doubled since Korea, to $672 billion), it has no goal in Asia but the continued independence of free peoples. "We did not choose to be the guardians at the gate," as Lyndon Johnson declared. "But there is no one else."

Not for Export. Some critics have faulted the U.S. for naively seeking to impose U.S.-style democracy on South Viet Nam. Conversely, others condemn Washington for supporting an undemocratic regime in Saigon. Both miss the essential point. Saigon may well suffer from instability, corruption and feudal social system, but as Freedom House Chairman Leo Cherne has written, "Far from wanting to export these defects, the South Vietnamese ask only to be left in peace to overcome them. This is the real tragedy of Viet Nam–that history has denied it the chance to grow and evolve in peace." The U.S. is there to give it that chance.

For all of Ho’s gibes that the Americans in Viet Nam are "imperialists" bent on fighting a "white man’s war," Saigon’s threatened government did not see the arriving soldiers as devils but as deliverers. Nonetheless, Westmoreland constantly advises his men to remember their proper role there. "Saigon’s sovereignty must be honored, protected and strengthened," he insists. "In 1954 this was a French war. Now it is a Vietnamese war, with us in support. It remains, and will remain just that." Nothing proves his point so eloquently as the casualty figures. In 1965 the U.S. suffered 1,241 killed in action and 5,687 wounded; the South Vietnamese lost 11,327 killed in action and 23,009 wounded. (The total since Jan. 1, 1961, when the Pentagon began counting casualties: U.S.: 1,484 killed in action, 7,337 wounded; Viet Nam: 30,427 killed in action, 63,000 wounded; Viet Cong 104,500 killed in action 250,000 wounded.)

"Wherever You Go." Pentagon officials quote the observation by a Viet Nam veteran in a letter home: "You can’t run away from Viet Nam because it will follow you wherever you go." While President Johnson insists that the U.S. will remain there as long as Saigon’s sovereignty is threatened, the war will inevitably confront him with profound problems at home.

For one thing, as the size and cost of the U.S. commitment grows, Americans will understandably expect their forces to go beyond containment and start reclaiming territory. So far, the results have been less than spectacular. Despite the war’s ever-mounting tempo the Saigon government at year’s end controlled only 57% of the population v. 23% under Communist domination, and 20% still in doubt. Physically, the Cong still occupied between 70% and 90% of the entire country, though much of it was barely habitable–dank mangrove swamps in the Mekong Delta, spiny ridges in the highlands, dense rain forests above Saigon.

In the next few months, the U.S. public can hardly demand major victories–at least until a serious supply bottleneck is broken and Westmoreland gets the extra combat divisions he has been pleading for. But as the U.S. troop level climbs toward 40,000 men, as the price of war begins to crimp Great Society programs and boost taxes, Americans may find it harder than ever to accept the long war predicted by the Administration Military men talk in terms of years, and though other officials insist that "something will give" long before that, few would risk curtailing the U.S. buildup.

If American patience wears thin, Lyndon Johnson may find himself in a two-way squeeze. From one side he will be under increasing pressure to bomb the North into oblivion. Already the U.S. has slit open the "red envelope" enfolding North Viet Nam’s major industrial centers with a raid on the sprawling Uong Bi power plant at Haiphong; in 18,600 sorties, bombers have plastered targets to within 30 miles of the Chinese border. Yet Hanoi is pouring more men and material into the South each month. On the opposite end of the spectrum, a long costly stalemate may well persuade more and more Americans that the pacifists and isolationists and columnists such as Walter Lippmann–not to mention Mao Tse-tung and Ho Chi Minh–were right all along in arguing that the U.S. has no business in Asia. If that feeling becomes general, the U.S. will be forced into the trap of seeking a negotiated settlement from a position of weakness–which at worst will give South Viet Nam to he Communists as effectively as any military defeat.

To Pierce the Apathy. Either way, Lyndon Johnson did not help his cause in 1965 by a lack of candor on the severity of the war or the scope of U.S. involvement in Viet Nam. "Light" and "moderate" are still the official euphemisms to describe U.S. losses in even the bloodiest engagements.

It is already clear that the war will be the central issue of this year’s elections–as it should be. Few could dispute Lyndon Johnson’s swift, determined action in meeting the Communist challenge. But it is also becoming a major day-to-day concern of all Americans. Thus far, the President has dealt effectively with the Vietniks and isolationists on the one hand and on the other with those who urge that North Viet Nam be bombed "back to the Stone Age." His chief failure has been one of articulation. He is, after all, no Churchill–but who is?

Nonetheless, Johnson has yet to address himself in particular to the great majority of Americans who generally support his Viet Nam policy, though not in many cases without a certain apprehension. To sustain the broad base of support that he will need as the war expands and the casualty lists lengthen, he will have to pierce the apathy of those who–as of now–trust the President to make the right decisions, but have no sense of involvement in Viet Nam. There is another sizable segment of the public that understands only too well the necessity of the U.S. presence in Asia, but expects of the President realistic information on the price and progress of the war.

To awaken and convince both groups, the President needs more than pulpit platitudes, and the American people will certainly demand more in 1966. Meanwhile, in return for their support in the difficult days of 1965, they have a right to expect more than 126 words on Viet Nam in this year’s State of the Union address.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy