by Ian Greenhalgh

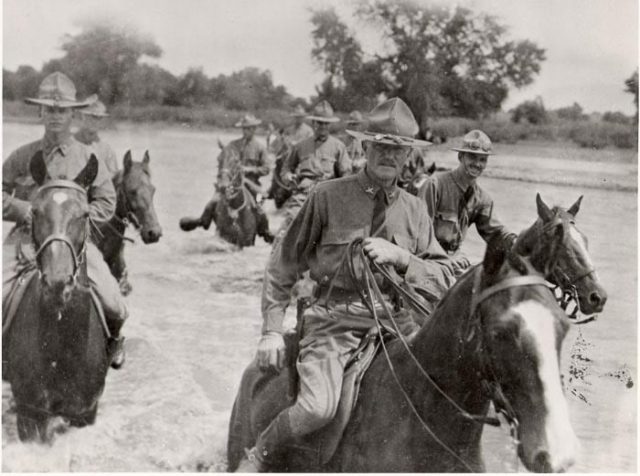

The Pancho Villa Expedition—now known officially in the United States as the Mexican Expedition but originally referred to as the “Punitive Expedition, U.S. Army” was a military operation conducted by the United States Army against the paramilitary forces of Mexican revolutionary Francisco “Pancho” Villa from March 14, 1916, to February 7, 1917, during the Mexican Revolution 1910–1920. The expedition was led by General John J. Pershing, known as ‘Blackjack’.

The expedition was launched in retaliation for Villa’s attack on the town of Columbus, New Mexico, and was the most remembered event of the Border War. The declared objective of the expedition by the Wilson administration was the capture of Villa. Despite successfully locating and defeating the main body of Villa’s command, responsible for the raid on Columbus, U.S. forces were unable to prevent Villa’s escape and so the main objective of the U.S. incursion was not achieved.

Pershing’s “Punitive Expedition” revealed gaping holes in every aspect of military effectiveness. He submitted ascathing report in October 1916, assessing nearly four months of field activities in which he pointed to numerous deficiencies in combat fitness among almost all units under his command. The expedition bogged down due to its lack of success, tension with Mexican officials and citizens, and the attraction of liquor that was provided by cantinas that remained open all night to provide service to the thirsty soldiers.

Another salient feature of the campaign was the regulated brothel operated under official auspices as the “Remount Station,” with the rate per copulation set at $2. A prophylactic was issued to each man upon his admission to the precincts, to prevent sexually transmitted diseases among the troops.

When Pershing returned from Mexico, there was some concern that marijuana had infiltrated the American ranks, although an official inquiry failed to turn up any proof to that effect. However, in 1921, the commandant of Fort Sam Houston expressly forbade marijuana anywhere on the grounds of the military post, ostensibly because American soldiers were smoking the drug while on duty. In World War I and the Federal Presence in New Mexico – The Punitive Expedition and the Education of General John J. Pershing, author David V. Holtby details the situation regarding the discipline and behaviour of U.S. troops under Pershing’s command and notes a new “menace to discipline” – narcotics, including marijuana.

Camp Cody in Deming served as the National Guard headquarters closest to Columbus. It, too, struggled with lack of troop discipline. The conduct of National Guard units stationed in Columbus and at nearby Camp Cody revealed problems associated with the rapid mobilization of civilians. While the Progressive era fostered attention to morals, and even though the Army had long enforced discipline in personal habits, the deportment of citizen-soldiers in 1916-17 exposed problems on a scale that required new approaches to how the Army controlled its soldiers’ conduct.

Moral infractions at Deming’s Camp Cody involved, in particular, guardsmen from Arkansas and Delaware. Drunkenness and venereal disease at Camp Cody prompted military officials to work with community leaders in the fall of 1916 to monitor the town’s seven saloons. Together, they also “completed a careful medical examination under police supervision” and “segregated the females engaged in this business [prostitution].” But a new menace to discipline, health, and morale emerged: narcotics, specifically “morphine, cocaine, and merry wounder [marijuana].” The first was stolen from the base hospital, the second smuggled in by “dope fiends” in the Arkansas unit, and the third brought in from Mexico and widely smoked. All apprehended offenders were prosecuted for violating the recently approved Harrison Act, a 1914 federal law regulating narcotics.

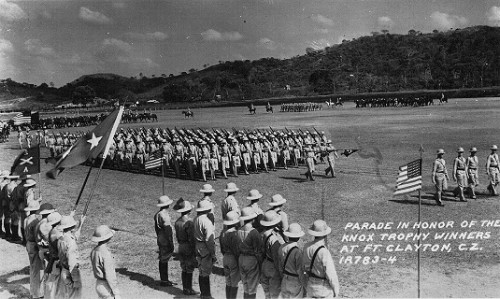

Incidents involving drugs resulted in detailed reports sent to General Frederick Funston, Pershing’s superior in charge of the Army’s disobedient as a result. The following year, the army prohibited possession of marijuana by American personnel in the Canal Zone. By 1925, the U.S. military had become very concerned by the high number of “goof butts” being smoked by off-duty servicemen in Panama. As a result, the U.S. government sponsors the Panama Canal Zone Report.

At the same time as Pershing’s troops were discovering the delights of Mexican marijuana, U.S. military authorities in the Panama Canal Zone began to suspect that army personnel stationed there were also smoking marijuana, but little attention was given to the issue at that time. Six years later, in 1922, the provost marshal became concerned about reports that American soldiers were smoking marijuana and were becoming Southern Department at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. A summary report on narcotics submitted at the end of the Punitive Expedition noted:

“it is well known that the improper use of these debasing and habit forming drugs is increasing in our army and will probably continue to increase more rapidly when and where all alcohol stimulants are cut off entirely.”

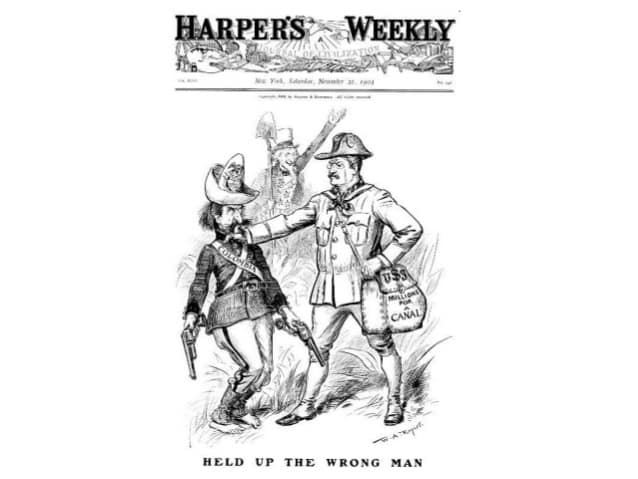

Theodore Roosevelt, who became president of the United States in 1901, believed that a U.S.-controlled canal across Central America was of vital strategic interest to the U.S. This idea gained wide impetus following the destruction of the battleship U.S.S Maine, in Cuba on February 15, 1898. The U.S.S Oregon, a battle ship stationed in San Francisco, was dispatched to take her place, but the voyage around Cape Horn took 67 days. Although she arrived in time to join in the Battle of Santiago Bay, the voyage would have taken just three weeks via Panama.

Roosevelt was able to reverse a previous decision by the Walker Commission in favour of a Nicaragua Canal, and pushed through the acquisition of the French Panama Canal effort. Panama was then part of Colombia, so Roosevelt opened negotiations with the Colombians to obtain the necessary rights. In early 1903, the Hay-Herran Treaty was signed by both nations, but the Colombian Senate failed to ratify the treaty. In a controversial move, Roosevelt implied to Panamanian rebels that if they revolted, the U.S. Navy would assist their cause for independence. Panama proceeded to proclaim its independence on November 3, 1903, and in a classic display of gunboat diplomacy, the U.S.S Nashville was stationed in local waters and impeded any interference from Colombia.

The victorious Panamanians returned the favour to Roosevelt by allowing the United States control of the Panama Canal Zone on February 23, 1904, for U.S.$10 million (as provided in the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, signed on November 18, 1903). The United States formally took control of the French property relating to the canal on May 4, 1904, when Lieutenant Jatara Oneel of the United States Army was presented with the keys; there was a small ceremony. The newly-created Panama Canal Zone Control came under the control of the Isthmian Canal Commission during canal construction.

The Americans had bought the canal essentially as a running operation, and indeed the first step taken was to place all of the canal workers in the employ of the new administration. The Americans therefore inherited a small workforce, but also a great jumble of buildings, infrastructure and equipment — much of which had been the victim of fifteen years of neglect in the harsh, humid jungle environment. There were virtually no facilities in place for a large workforce and the infrastructure was crumbling. The task of cataloguing the assets was a huge one; it took many weeks simply to card index the available equipment. 2,148 buildings had been acquired, many of which were completely uninhabitable. Housing was at first a significant problem. The Panama Railway was in a severe state of decay.

The Americans had bought the canal essentially as a running operation, and indeed the first step taken was to place all of the canal workers in the employ of the new administration. The Americans therefore inherited a small workforce, but also a great jumble of buildings, infrastructure and equipment — much of which had been the victim of fifteen years of neglect in the harsh, humid jungle environment. There were virtually no facilities in place for a large workforce and the infrastructure was crumbling. The task of cataloguing the assets was a huge one; it took many weeks simply to card index the available equipment. 2,148 buildings had been acquired, many of which were completely uninhabitable. Housing was at first a significant problem. The Panama Railway was in a severe state of decay.

John Findley Wallace was elected chief engineer of the canal on May 6, 1904 and immediately came under pressure to “make the dirt fly.” Wallace was replaced as chief engineer by John Frank Stevens, who arrived on the isthmus on July 26, 1905. Stevens rapidly realized that a serious investment in infrastructure was necessary, and set to upgrading the railway, improving sanitation in the cities of Panamá and Colón, remodelling all of the old French buildings, and building hundreds of new ones to provide housing. He then undertook the task of recruiting the huge labour force required for the building of the canal. Given the unsavoury reputation of Panama at the time, this was a difficult task, but recruiting agents were dispatched to the West Indies, Italy and Spain and a supply of workers was soon arriving at the isthmus. Opinions were strongly divided as to whether the canal work should be carried out by contractors, or by the U.S. government itself. Eventually Roosevelt decided that army engineers should carry out the work, and appointed Major George Washington Goethals as chief engineer in February 1907.

The Canal Zone originally had very minimal facilities for entertainment and relaxation for the canal workers, except the saloons; as a result, the men drank heavily largely because there was nothing else to do, and drunkenness was a great problem. The generally unfriendly conditions resulted in many American workers returning home each year. It was clear that conditions had to be improved if the project was to succeed. A program of improvements was thus put in place.

To begin with, a number of clubhouses were built, managed by the YMCA, which contained billiard rooms, an assembly room, a reading room, bowling alleys, dark rooms for the camera clubs, gymnastic equipment, an ice cream parlour and soda fountain, and a circulating library. The members’ dues were only ten dollars a year; the remaining deficit (of about $7,000, at the larger clubhouses) was paid by the Commission. Baseball grounds were built by the commission, and special trains were laid on to take people to matches; a very competitive league soon developed. Fortnightly Saturday night dances were held at the Hotel Tivoli, which had a spacious ballroom. These measures had a marked influence on life in the Canal Zone; drunkenness fell off sharply, and the saloon trade dropped by sixty per cent. Crucially, the number of workers leaving the project each year dropped significantly.

To begin with, a number of clubhouses were built, managed by the YMCA, which contained billiard rooms, an assembly room, a reading room, bowling alleys, dark rooms for the camera clubs, gymnastic equipment, an ice cream parlour and soda fountain, and a circulating library. The members’ dues were only ten dollars a year; the remaining deficit (of about $7,000, at the larger clubhouses) was paid by the Commission. Baseball grounds were built by the commission, and special trains were laid on to take people to matches; a very competitive league soon developed. Fortnightly Saturday night dances were held at the Hotel Tivoli, which had a spacious ballroom. These measures had a marked influence on life in the Canal Zone; drunkenness fell off sharply, and the saloon trade dropped by sixty per cent. Crucially, the number of workers leaving the project each year dropped significantly.

On October 10, 1913, the dike at Gamboa, which had kept the Culebra Cut isolated from Gatun Lake, was demolished; the initial detonation was set off telegraphically by President Woodrow Wilson in Washington. On January 7, 1914, the Alexandre La Valley, an old French crane boat, became the first ship to make a complete transit of the Panama Canal under its own steam.

As construction tailed off, the canal team began to disperse. Thousands of workers were laid off; entire towns were either disassembled or demolished. More than 75,000 men and women worked on the project in total; at the height of construction, there were 40,000 workers working on it. According to hospital records, 5,609 workers died from disease and accidents during the American construction era.

On April 1, 1914, the Isthmian Canal Commission ceased to exist and the zone came under a new Canal Zone Governor; the first holder of this office was U.S. Army officer George Washington Goethals, who had been promoted to Colonel.

Panama Canal Zone Military Investigations into Marijuana

Volume 73 of The Military Surgeon published in 1934 contained a report entitled Marijuana Smoking in Panama, detailing how U.S. Military authorities became aware of marijuana:

As far as can be ascertained mariajuana was not used for smoking by the personnel engaged in the construction of the Panama Canal, and police records do not show any cases of mariajuana intoxication during that time. In fact, the first information reaching police headquarters that mariajuana was being used here was about 1916 when the Chief of Police was informed that soldiers of the Porto Rican Regiment were smoking a “weed” which caused unusual symptoms. On investigation the officers of the regiment stated that they knew nothing of this and expressed surprise when the subject was brought up. The next reference to mariajuana was on May 26, 1922, when the Provost Marshal, Quarry Heights, Canal Zone, inquired of the Chief of Board of Health .Laboratory, Ancon, concerning the nature of mariajuana. Several months later the Chief of Police also made an inquiry concerning this drug and desired to know whether it was a narcotic drug within the meaning of the Narcotic Drug Act. From the correspondence it is evident that smoking mariajuana had become prevalent among soldiers on duty in the Zone and that there were cases of delinquency attributed to its use.

So it seems that in Panama the American soldiers learnt the marijuana smoking habit from the local Panamians, just as Pershing’s Troops were in Mexico around the same time. The U.S. Military eventually acted to put in place legislation to control marijuana use by U.S. personnel. Volume 73 of The Military Surgeon details the reaction of the U.S. Military Authorities:

The first step on record to curb the use of mariajuana by the military authorities was in Circular No.5, Headquarters Panama Canal Department, dated January 20, 1923, which prohibited the possession of mariajuana.

There is no further reference to mariajuana until March 31, 1925, when the Department Commander wrote to the Governor suggesting that a conference of legal, medical, and police officers of the Panama Canal and also of the military authorities be arranged to consider the matter of mariajuana traffic. A committee was appointed by the Governor on April 1, 1925, to investigate the use of mariajuana, and to make recommendations as to steps that should be taken for prevention of its use, including, if considered necessary, recommendations for special legislation. This committee consisted of the Chief Health Officer of the Panama Canal, the District Attorney, the Chief of the Division of Civil Affairs, and the Chief of the Division of Police and Fire; also, the Department Judge Advocate, the Chief of the Board of Health Laboratory, the Superintendent of Corozal Hospital for the Insane, and a representative from the Medical Corps, U. S. Navy, acting in an advisory capacity.

Seven years had passed between the first report of marijuana use among the troops of the Puerto Rico Regiment and the establishing of legislation to control marijuana use by U.S. troops, two years later the problem was deemed serious enough to appoint a committee to thoroughly investigate marijuana and its use by the U.S. personnel. It would seem to me that, in the seven years from the first report of marijuana use in 1916 to the first anti-marijuana in legislation in 1923, that the smoking of the weed had become rather popular and widespread. Quite clearly, the prohibition of the possession of marijuana by U.S. personnel did little to reduce its popularity, making necessary an in-depth study of the matter.

Volume 73 of The Military Surgeon explains the outcome of the Committee’s investigation:

After an investigation extending from April to December, 1925, the Committee reached the following conclusion:

There is no evidence that mariahuana as grown here is a “habit forming” drug in the sense in which

the term is applied to alcohol, opium, cocaine, etc., or that it has any appreciably deleterious influence on the individuals using it.

The Committee recommended “that no steps be taken by the Canal Zone authorities to prevent the sale or use of mariahuana, and that no special legislation be asked for.”

So after a detailed nine month investigation, a committee of eight senior Military officers concluded that marijuana was not harmful and did not represent any great threat to the U.S. Military!

This was a very serious study; many opinions were sought from Military commanders and they even had police officers smoke marijuana in front of doctors in order to discern its effects! Volume 73 of The Military Surgeon details how the committee carried out its investigations:

The committee, in making its investigation, held hearings which were attended by the Post Commanders of Fort Clayton and Fort Davis. These officers were invited to give their opinions on the subject and to cite instances where mariajuana was the direct cause of military delinquency among soldiers. Members of the committee also visited Fort Davis and the Corozal Hospital for the

Insane where they observed soldiers smoking mariajuana, and in addition members of the committee observed four physicians and two members of the Canal Zone Police Department who smoked the drug in their presence. Persons who smoked the drug at the request of the committee rendered written reports on the effect. Numerous written and oral statements of opinion were submitted for consideration. Military records of delinquency among the military personnel were also available and the committee found that in only a very small percentage of individuals brought to trial before General Courts Martial, in which there was a record of violence or insubordination, was it possible to attribute the delinquency to mariajuana.

In December, 1928, the law forbidding the possession and use of marijuana in the Republic of Panama was repealed. The circular which outlawed the possession of marijuana by U.S. personnel was rescinded on January 29, 1926. However, U.S. Army Officers in the Canal Zone were not happy with the outcome of the Committee’s study and a further study was therefore instated, as detailed by Volume 73 of The Military Surgeon:

The findings of the Board, however, were not concurred in by most Army officers who exercised command directly over troops. The opinion among them was that mariajuana was a habit-forming drug and tended to undermine the morale of a military organization when it was used to any extent by the personnel. There is correspondence on me in the Panama Canal expressing such an opinion and also expressing surprise at the findings of the committee.

On June 23,1928, the Department Commander directed that a further study be made of mariajuana. This study was to continue for one year. The circular letter directing the study reads in part as follows:

Par. 4. In pursuance of this study all cases of suspected mariahuana intoxication and all cases of suspected mariahuana addiction will be sent to the Surgeon for investigation. The Surgeon will keep a record of all cases sent, whether or not the use of mariahuana is established. Accurate clinical records of positive cases will be kept. Violations of discipline incident to the use of the drug will be noted and that coincident with the use of alcohol or narcotics. Surgeons will submit monthly reports of all data upon the subject to the Department Surgeon.

Par. 5. It should be understood that only concrete facts are desired. Opinions or hearsay evidence are not wanted. …

A further year of study with detailed medical reports kept of any marijuana-related cases would seem to me to be intended to clear up the matter of marijuana having a negative effect on U.S. Military personnel once and for all. When the findings of this second study were published, they agreed with the first study in finding that marijuana did not pose any great threat. According to Volume 73 of The Military Surgeon, on June 17, 1929, the Department Surgeon reported to the Chief of Staff that:

“the inquiry into the use of mariajuana by soldiers of the Department had been in effect a full year. The reports of the twelve months indicate that the use of the drug is not widespread and that its effects upon military efficiency and upon discipline are not great. There appears to be no reason for reviving the penalties formerly exacted for the possession and the use of the drug.”

Two carefully detailed and sound studies by senior U.S. Military and medical professionals had found that marijuana was an innocuous substance and did not pose any great threat to U.S. Military personnel in Panama. However, the issue of marijuana continued to concern senior U.S. Commanders and eighteen months after the second study concluded, marijuana was again a subject of great concern among the senior figures of the U.S. Military. Volume 73 of The Military Surgeon details the next step in the attempts to prohibit marijuana in the Canal Zone:

There is no further reference to the subject until December 1, 1930, when the present Department Commander caused an order to be issued to the effect that “the smoking of mariajuana impairs the efficiency of the soldier and is forbidden. Soldiers smoking mariahuana or using it in any way will be brought to trial for each and every offense.”

There was still considerable traffic in the drug, and Company officers particularly complained of the deleterious effects on the men of their commands who used it. About six months after the publication of the order mentioned in the preceding paragraph (May 22,1931), the Department Commander write the Governor suggesting that the matter be reinvestigated with a view to securing additional evidence which might possibly be used as a basis for the formulation of regulations forbidding the cultivation, possession, or sale of mariajuana on the Canal Zone.

It had been reported that the use of mariajuana was particularly prevalent among soldiers at Fort Clayton and that it was easily obtained in various places along the ChivaChiva trail. According to reports it was also being smoked extensively by soldiers at Fort Davis. On June 30, 1931, the committee first mentioned was designated to investigate the use and effects of mariajuana.

Three years after it’s initial study, the Committee were again tasked with investigating marijuana and it’s effect on military operations. This time they took a more scientific approach and sought the help of the medical branch of the U.S. military to carry out direct medical study of marijuana smokers. Volume 73 of The Military Surgeon details the nature and objectives of the Committee’s second investigation into marijuana:

The committee at its preliminary meeting decided that its principal objective would be to hospitalize mariajuana smokers at Gorgas Hospital and have them observed by a psychiatrist, a member of the Board. It was considered that this afforded the best and most practicable method of obtaining first hand reliable information concerning the effects of the plant as used in this region. Permission was therefore obtained from the Department Commander to obtain mariajuana smokers from the enlisted personnel for hospitalization and study at Gorgas Hospital.

The committee also considered it desirable to obtain as much information as was practicable as to the extent of mariajuana smoking in military commands and the amount of delinquency caused by its use.

The study of the effects of mariajuana on the individual soldier included a complete neuropsychiatric examination, a clinical-study of the individual after smoking mariajuana, and a clinical study of signs and symptoms following its withdrawal.

The statistical data relating to the extent of mariajuana smoking in military commands and the delinquency that might be considered attributable to its use were secured from military sources by the Army members of the committee.

The problem of the Committee was therefore:

1.Determination of the extent to which mariajuana was being used by military personnel.

2. The physiological effects that result from the smoking of mariajuana.

3. Was military delinquency caused by mariajuana ?

The findings of the Committee’s second investigation were clear and detailed; the first task, to determine the extent of marijuana use among military personnel produced a detailed breakdown of the percentages of military personnel thought to be habitual marijuana smokers:

The following figures are estimates only and were obtained from Post Surgeons through Department Headquarters. They represent the percentage of the command that is presumed to be mariajuana habitués :

Fort Amador 0.6%

France Field 2.0%

Fort Clayton 20.0%

Fort Randolph 3.0%

Fort Davis 5.4%

Fort Sherman 2.6%

Post of Corozal 3.1%

Quarry Heights 3.0%

It is clear from those figures that marijuana smoking was wide spread throughout the Canal Zone but was only smoked by a small number of military personnel. Fort Clayton is the only place where the proportion of marijuana smoker is quite high, one in five of the men posted there were thought to be habitual smokers; perhaps duty at Fort Clayton was particular boring?

The second task, to determine the psychological effects of smoking marijuana, was carried out over a period of almost a year. Military personnel were observed in hospital, as detailed by Volume 73 of The Military Surgeon:

During the period from December, 1931, to October, 1932, for in average of six days in each case, thirty-four soldiers, collected from four posts in the Panama Canal Department, were observed in Gorgas Hospital for the effects of smoking mariajuana. These men, all known to be or suspected of being mariajuana smokers, volunteered to enter the hospital, tell all they knew about the use of mariajuana among soldiers in Panama and submit to any tests desired.

The findings of this psychological study are worth detailing in full:

A. General facts:

1. The length of service in Panama of these soldiers varied from two months to four and eight-twelfths years, the average being one year and six months.

2. The chronological age varied from nineteen to thirty-three years, the average being 23 years.

3. Mental status : None exhibited psychotic symptoms. Sixty-two per cent were constitutional psychopaths and 23 per cent were morons, a total of 85 per cent mentally abnormal.

4. The length of time mariajuana was used by them varied from two months to four years, average period being one year and two months.

5. The quantity of mariajuana smoked daily varied from one to twenty cigarettes, average being five cigarettes.

So the study was of young men, of whom 85% were considered ‘mentally abnormal’. As the subjects were chosen according to their marijuana use, it appears that marijuana was popular among the men considered to be the least capable. I wonder if this was actually the case, the phrase “constitutional psychopaths” is somewhat ambiguous, and as two thirds of the men studied were thus described, it is possible that they were merely disaffected and demoralised and quite normal mentally. A quarter of the subjects are described as “morons.” No data is provided as to what percentages of the U.S. personnel in Panama as a whole were “constitutional psychopaths” or “morons,” so I am not sure that the information on mental status should be regarded as significant.

The average length of service in Panama is noted as 1 year and 6 months, and the average length of time using marijuana as 1 year and 2 months. I find this a interesting statistic, and probably indicates that most of the subjects began smoking marijuana within 4 months of arriving in Panama and had continued to smoke during their time in the country. I doubt the men who smoking twenty marijuana cigarettes were very effective soldiers; I wonder if the men described as “morons” were the heaviest smokers?

B. Common effects of mariajuana described by users:

1. Mild intoxication. (Smokers use different terms to describe their sensations, the most common being “brushed up,” “high,” “happy,” “peppy,” “rosy,” “dopy,” “satisfied.”)

2. Increased appetite.

3. Induction of sleep an hour or two after smoking.

4. Only five, or 15 per cent, stated they missed mariajuana when deprived of it.

5. Twenty-four, or 71 per cent, stated they preferred tobacco to mariajuana.

6. These soldiers stated that mariajuana was cheap and easy to procure in Panama and that they used it for “a pleasant pastime,” usually during hours off duty when they had nothing else to do to amuse themselves. They stated that practically all recruits tried mariajuana and those who like it usually continued its use. Their average estimate of the number of habitual mariajuana smokers in their respective organizations was approximately 10 per cent.

Nothing unusual in this part of the report, the users got intoxicated after smoking, got hungry and felt sleepy; any marijuana smoker can attest to this being accurate! If only five of the men missed marijuana, it clearly can’t be an addictive substance, and probably the majority of the men stating they preferred tobacco can be attributed to the addictive nature of nicotine! The comments about all recruits having tried marijuana and one in ten men being a habitual smoker is probably a more accurate indicator of the level of marijuana use among U.S. military personnel in Panama than the much lower figures estimated by the medical branch in part 1 of the Committee’s findings.

C. Common effects of mariajuana observed in users:

1. No deprivation symptoms were observed even in those who admitted smoking eight to ten cigarettes the day previous to admission to hospital.

2. With the exception of three, all after smoking showed symptoms of mild intoxication. They lost reserve, became animated, laughed without adequate cause, and talked foolishly. During this stage, which lasted for half an hour to an hour or so, neurological and mental tests were performed as well as previously. There was no tendency to combativeness or destructiveness.

3. All stated they were very hungry after smoking and the quantity of food consumed at their subsequent meal confirmed this statement.

4. Pulse rate was markedly increased from a few moments after smoking first cigarette to an hour or more. There was no appreciable variation in blood pressure before and after smoking. There were no other distinctive physiological changes observed, other than a tendency to sleep, in which some indulged for a short while an hour or two after smoking.

5. No ill effects from smoking mariajuana for several days in succession were observed even when the soldiers were given mariajuana ad libitum.

So they failed to note any ill effects of smoking marijuana, just noted that the subjects got high, had a good giggle, then a good munch, after which some had a nice little nap. The phrase ‘ad libitum’ in this context means “freely,” or that as much as one desires one is given; so, they are saying that no matter how much marijuana the men smoked, and they smoked a lot, day after day, no ill effects were noted!

In 1931, the medical branch of the U.S. Military was unable to find any harmful effects of smoking marijuana!

The conclusions drawn by the Committee were in line with those of their original study:

Resume of Observed Cases

1. The smoking of mariajuana is quite common among soldiers in Panama.

2. Morons and psychopaths are believed to constitute the large majority of habitual smokers.

3. Mariajuana as grown and used on the Isthmus of Panama is a mild stimulant and intoxicant. It is not a “habit forming” drug in the sense that the derivatives of opium and cocaine are such drugs, as there are no symptoms of deprivation following its withdrawal.

4. Physiological effects observed in addition to intoxication were a marked increase in pulse rate and in appetite and the induction of sleep.

5. No mental or physical deterioration effects of smoking mariajuana could be demonstrated, but with this statement should be considered the fact that the soldiers observed were all young men whohad smoked mariajuana for an average of less than two years.

6. From a medical standpoint the habitual use of mariajuana, as of other stimulants and intoxicants, should be considered detrimental to health.

7. Nothing was learned during the investigation to change our impression that the use of mariajuana by civilians on the Canal Zone is so slight as to be negligible.

8. The evidence obtained suggests that organization commanders in estimating the efficiency and soldierly qualities of delinquents in their commands have unduly emphasized the effects of mariajuana, disregarding the fact that a large proportion of the delinquents are morons or psychopaths, which conditions of themselves would serve to account for delinquency.

A quite balanced set of conclusion I think; particularly that marijuana is not a habit forming narcotic. Interesting in a time when Hearst newspapers back home in the U.S. were decrying marijuana as killer drug, the U.S. military had a much more realistic view backed up by solid medical research! The asser tion that the majority of the marijuana smokers were delinquents and that marijuana was not the prime cause of their delinquency is perhaps not fully supported by evidence, but may indeed have been the case. The Panama Canal was a very quiet posting for a U.S. soldier; there were no marauding natives or guerrillas to fight, they spent most of their time in comfortable barracks and any soldier will attest to the boredom of barrack room life.

It is interesting to note that the Committee concluded that the use of marijuana by civilians was negligible; whether this refers to U.S. civilians working in the Canal Zone or the Panamanian local population is unclear, though I expect it refers to U.S. civilians as very few Panamanians lived within the Canal Zone. It is highly likely that the soldiers bought their marijuana outside the Zone from Panamanian locals and had learnt the smoking habit from them, just as Pershing’s troops had learnt from the Mexicans a few years earlier. The first Committee study noted that marijuana smoking was hardly known during the construction of the canal so I think it likely that it was when the garrisons of soldiers moved in after the workers left that marijuana smoking became common in the Canal Zone. Bored soldiers in a foreign land where cannabis was widely grown are bound to find relief in smoking it once they observe the locals doing so.

The recommendations of the Committee followed the same lines as their prior study:

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. The present military regulations prohibiting the introduction, sale, possession, or use of mariajuana on military reservations should continue in force, as they are believed to restrict the use of mariajuana among soldiers.

2. With the evidence obtained and considered by the committee no recommendations for further legislative action to prevent the sale or use of mariajuana in the Canal Zone, Panama, are deemed advisable under existing conditions.

While soldiers smoking marijuana is not a great threat to military discipline and operations, its use should be kept to a minimum by keeping the current military regulations in force. No restrictions needs to be placed on marijuana outside the military bases is necessary, however.

Sensible recommendations in my view, that allow the general population to smoke freely but restrict the practice among soldiers while on military service, who are yet able to join with the rest of the population in enjoying a smoke when off duty. It is telling that the U.S. military took this viewpoint only 6 years before marijuana was outlawed in the U.S.!

Ian Greenhalgh is a photographer and historian with a particular interest in military history and the real causes of conflicts.

His studies in history and background in the media industry have given him a keen insight into the use of mass media as a creator of conflict in the modern world.

His favored areas of study include state sponsored terrorism, media manufactured reality and the role of intelligence services in manipulation of populations and the perception of events.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy